City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (20 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

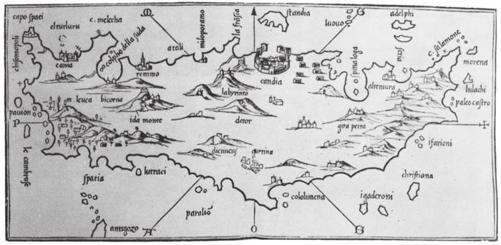

Venetian map of Crete

The island was at the crossroads of the Republic’s two great trading routes – those that led to Constantinople and the Black Sea, and those that went on to the spice markets of Syria and Egypt. It was the back station for supplying the crusader ports of the Holy Land; the place for warehousing and trans-shipping goods; for repairing and reprovisioning the merchant galleys; for naval operations throughout the Aegean in times of war. Groggy pilgrims bound for the Holy Land stepped ashore here for a brief respite from the sea. Merchants resold silk and pepper, dodging the intermittent papal bans imposed on trading with the infidel; news was exchanged and bargains struck. After 1381, when the practice was banned in Venice, Crete became the illicit hub of the Republic’s slave trade. In the great barrel-vaulted galley sheds of Candia and Canea, the duchy of Crete kept its own fleet to patrol the coast against pirates, crewed by press-ganged Cretan peasants. Candia itself was a faithful replica of the Venetian world, with its Church of St Mark fronting the ducal palace across a main square, its Franciscan friary, its loggia and its Jewish quarter pressed up against the city walls. From the main thoroughfare, the

ruga maestra

, running gently downhill to the harbour, the sea

was an abiding presence, sometimes whipped into grey fury by the north wind pummelling the breakwater, sometimes calm. From here homesick townsfolk and anxious merchants could watch the ships making the awkward turn into the narrow entrance of Candia’s harbour, and could see them depart again down the sea roads to Cyprus, Alexandria and Beirut; above all to Constantinople.

The maritime trunk route to Constantinople was critical in the map of Venetian trade. It passed via Crete through the scattered islands of the central Aegean – the Archipelago – fragments of rock speckling the surface of the sea. At the centre of these lay the Cyclades, the Circle the Greeks called them, grouped around Delos, once the religious centre of the ancient Hellenic world, now a haven for pirates drawing water from its sacred lake. The islands, separated by a few miles of flat sea, comprised a set of individual kingdoms. Naxos, large and well-watered, famous for its fertile valleys, was the most promising of the group; then volcanic Santorini; Milos famous for obsidian; Seriphos, the best harbour in the Aegean, so rich in iron ore that it confused the compasses of passing ships; pirate-haunted Andros.

Venice had been gifted all these islands by the treaty of 1204, yet it had neither the resources nor the keen economic interest to occupy them as a state enterprise. They were too small and too many to be garrisoned by Venetian forces, yet neither could they be ignored. Their harbours provided shelter in a storm, places to take on fresh water and heave to; unoccupied they represented danger from pirates, threatening the seaways north. With a keen eye to cost–benefit analysis, the Republic threw them open to private venture. Some time around 1205, Marco Sanudo, nephew of Enrico Dandolo, resigned his position as a judge in Constantinople, equipped eight galleys with the support of other enterprising nobles, and sailed forth to carve out his own private kingdom in the Cyclades. He was determined to do or die, not for the glory of the Republic, but for his own cause. Finding the castle at Naxos – the jewel of the central Aegean – occupied by Genoese pirates, he resolved that there would be no retreat. He burned his boats,

besieged the pirates for five weeks, ousted them, and declared himself the Duke of Naxos. Within a decade the Cyclades had morphed into separate micro-kingdoms, property of a swarm of aristocratic adventurers, keen for the individual glory on which Venice tended to frown. Marino Dandolo, another nephew of the old doge, held Andros, the Ghisi brothers Tinos and Mykonos, the Barozzi occupied Santorini. Some possessions were doled out whimsically; Marco Venier was granted Kythera, which the Italians called Cerigo, the reputed birthplace of Venus, on the basis of the similarity of names. In each place, the owners constructed castles out of ransacked Greek temples and carved their coats of arms above the door, maintained miniature navies with which they fought each other, built Catholic churches and imported Venetian priests to chant the Latin rite.

An exotic hybrid world grew up in the central Aegean. The majority of the Greeks remained loyal to their Orthodox faith but generally tolerated their new overlords; the Venetian adventurers at least provided some measure of protection against the scourge of piracy, which ravaged the islands of the sea. Despite the prospect of a gold rush which the opening up of the Archipelago seemed to create, the islands contained precious little gold.

The saga of the Venetian Aegean was colourful, violent and, in places, surprisingly long-lasting. The duchy of Naxos did not expire until 1566; the most northern island of the group, Tinos, remained faithful to Venice until 1715. The Republic, however, was to find these freebooting duchies not always to its liking. Marco Sanudo, conqueror of Naxos, lived the life of a charmed adventurer, seeking advantage where he could. He helped suppress a rebellion on Crete, but finding the rewards not forthcoming, changed sides and made cause with the Cretan rebels until he was chased back to Naxos. Undeterred, he ill-advisedly attacked Smyrna, where he was captured by the emperor of Nice; his charm was such that he managed to exchange a dungeon for the hand of the emperor’s sister. The Ghisi, at least, were loyal to the Republic in the nearby fortress of Mykonos. They burned a large candle in their island

church on St Mark’s day and sang the saint’s praise. More often, the dukes of the Archipelago launched their tiny fleets across the summer seas and fought petty wars. The Cyclades became a zone of intermittent privatised battle, and its lords were by turns quarrelsome, treacherous and mad. Some were ruled by absentee landlords on Crete; Andros from a Venetian palazzo; Seriphos by the unspeakable Nicolo Adoldo, given to inviting prominent citizens of the island to dinner, then hurling them from the castle windows when they refused his demands for cash. When the crescendo of complaints grew too loud Venice was forced to intervene. Adoldo was banished from Seriphos for ever and languished for a while in a Venetian gaol. But Venice tended to be pragmatic in these matters – Adoldo was piously buried in the church he endowed in the city; it winked at the murder of the last Sanudo to rule Naxos by a usurper more favourable to itself. Nor was it averse to direct intervention. When an heiress to the duchy of Naxos took a fancy to a Genoese nobleman, she was abducted to Crete and ‘persuaded’ to marry a more suitable Venetian lord. This strategy of occupation by proxy had its drawbacks – and in time Venice would be forced to accept direct ownership of many of these places – but at least the petty lordlings of the Aegean damped down the level of piracy and ensured the merchant fleets a more steady passage through the ambush zones of the Archipelago.

Beyond it all lay Constantinople. When the Venetian fleet made its way up the Dardanelles in the summer of 1203 and gazed up at the sea walls of the city, they were confronted with a daunting and hostile bastion. After 1204, the city was Venice’s second home. Venetian priests sang the Latin rites in the great mosaic church of Hagia Sophia; Venetian ships tied up securely at their own wharfs in the Golden Horn, unloading goods into tax-free warehouses. The Republic’s erstwhile competitors, the Genoese and the Pisans, with whom it had brawled repeatedly under the wary gaze of the Byzantine emperors, were barred from the city’s trade. And, for the first time, Venetian ships also had the freedom to pass up the straits of the Bosphorus into the Black Sea and seek new

points of contact with the furthest Orient. Thousands of Venetians flooded back into the city to trade and live. So powerful was the attraction of Constantinople, that one doge, Jacopo Tiepolo, for a time

podesta

(mayor) there, was said to have proposed moving the centre of Venetian government to the city. Venice, once the puny satellite of the Byzantine Empire, idly contemplated replacing it. And the steady, if hard-fought, consolidation of its colonies and bases across the eastern Mediterranean promised to turn the sea into a Venetian lake. Its merchants were everywhere. Tiepolo established trading agreements with Alexandria, Beirut, Aleppo and Rhodes. He articulated a consistent policy and a continuity of effort that would last for hundreds of years. Venetian objectives remained frighteningly consistent – to secure trading opportunities on the most advantageous terms. The means, however, were endlessly flexible. The Venetians were opportunists born for the bargain, ready to sail wherever the current would run.

Destiny lay in the East, in its spices, its silks, its marble pillars and its jewelled icons, and the riches of the Orient flowed back, not only into the coffers of Venetian merchants, stored in the barred ground-floor warehouses of their great palazzos fronting the Grand Canal, but also into the visual imagery of the city. The mosaicists who decorated the Church of St Mark in the thirteenth century imaged the biblical world of the Levant. They reproduced the lighthouse from Alexandria; camels with tasselled reins; merchants leading Joseph into Egypt. An oriental note also starts to pervade the grand architecture of the city.

*

By the time that Renier Zeno became doge in 1253, Easter was celebrated with the splendour of Byzantine ritual. The doge walked in solemn procession the short distance from the ducal palace to the Church of St Mark. He was preceded by eight men holding banners of silk and gold bearing the saint’s image; then two maidens, one carrying the doge’s chair, the other its golden cushions, six musicians with silver trumpets, two with cymbals of pure silver, then a priest carrying a huge cross of gold and silver,

embedded with precious stones, another an ornate gospel; twenty-two chaplains of St Mark’s in golden copes followed, singing psalms, and then the doge himself walking beneath the ritual umbrella of gold cloth, accompanied by the city’s primate and the priest who would sing the mass. The doge, looking for all the world like a Byzantine emperor, wore cloth of gold and a crown of jewelled gold and carried a large candle, and behind came a noble carrying the ducal sword, then all the other nobles and men of distinction.

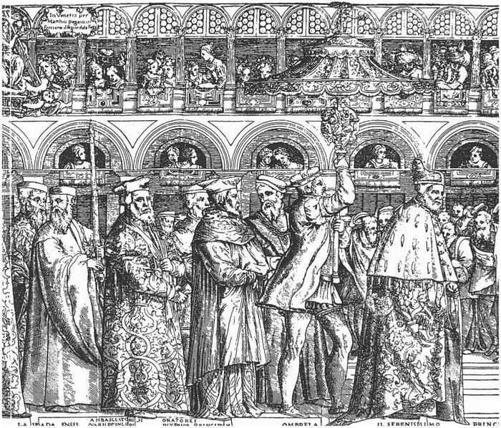

The procession of a doge

As they processed along the facade of the church, past the porphyry columns taken from crusader Acre and those plundered from Constantinople, it was as if Venice had stolen not only the marble, icons and pillars of Constantinople, but its imperial imagery, its love of ceremonial, its soul. In the submarine gloom of the mother church, Easter was celebrated with words

that linked sacred and profane, the risen Christ and the Venetian Stato da Mar: ‘Christ conquers!’ went up the cry. ‘Christ reigns! Christ rules! To our lord Renier Zeno, illustrious doge of Venice, Dalmatia and Croatia, and lord of a quarter and half a quarter of the empire of Romania, salvation, honour, life and victory! O, St Mark, lend him aid!’

The events of 1204 amplified Venice’s sense of itself. A growing assumption of imperial grandeur began to possess the little Republic, as if in the shimmering reflection of the spring canals, Venice was morphing into Constantinople.

*

The acclamation of the Stato da Mar would be followed a few weeks later each year by a claim to ownership of the sea itself at another great ceremony: the Senza, on Ascension Day. When Doge Orseolo had departed from the lagoon in the year 1000, this had been a simple blessing. After 1204, it became an increasingly elaborate expression of the city’s sense of mystical union with the sea. The doge, ermine-robed and wearing the

corno

, the pointed hat that symbolised the majesty of the Republic, was piped aboard his ceremonial barge at the quay in front of his palace. Nothing expressed the city’s maritime pride so richly as the

Bucintoro

, the Golden Boat. This majestic double-decker vessel, ornately gilded and painted with heraldic lions and sea creatures, covered by a crimson canopy and rowed by 168 men, pulled away from the quay. Golden oars dashed the waters of the lagoon. In the prow a figurehead representing justice held aloft a set of scales and a raised sword. The swallow-tailed banner of St Mark billowed from the masthead. Cannon fire crashed; pipes shrilled; drums beat a rapt tattoo. Accompanied by an armada of gondolas and sailing boats, the

Bucintoro

rowed out into the mouth of the Adriatic. Here the bishop uttered the ritual supplication: ‘Grant, O Lord, that for us and all who sail thereon, the sea may be calm and quiet,’ and the doge took a golden wedding ring from his finger and tossed it into the depths with the time-honoured words: ‘We wed thee, O Sea, in token of our true and perpetual dominion over thee.’