City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (24 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

Genoa quickly established a winning lead. After the fall of the Latin kingdom in 1261 they were granted free access to the sea. Venice was barred. The Genoese pushed energetically into the new zone and began to ring the coasts with settlements. They established trading posts on the north shore with a headquarters at Caffa on the Crimean peninsula, which brought them into close contact with the khans of the Golden Horde. They were soon able to control the grain trade at the mouth of the Danube; they struck deals with the small Greek kingdom of Trebizond and from there travelled overland to the important Mongol market at Tabriz. Genoa was ideally placed: backed by its secure base at

Galata across the Golden Horn from Constantinople, it strived for commercial monopoly. Suddenly Venice was playing catch-up. The Venetians were hungry for Black Sea grain and struggled to develop their own footholds. When Acre fell in 1291 and the pope banned trade with the Muslim lands, the stakes in the game increased; they would double again in 1324 when the papal ban became absolute. For fifty years – from the 1290s until 1345 – the emporia of the Black Sea became the warehouse of the world. Both republics realised instantly what was stake. Genoa was intent on maintaining a monopoly; Venice on finding a way in.

With the squeezing of opportunities elsewhere, the commercial competition in the Black Sea intensified. It only took an inopportune meeting of two armed and competitive merchant convoys, a flung insult, a sea brawl, an exchange of derogatory diplomatic notes with financial demands to lead to hostilities. A second Genoese war broke out in 1294 and lasted five years. It was the mirror image of the first; this time Genoa won the set-piece sea battles but suffered huge commercial damage. The engagements involved random, chaotic and opportunistic acts of piracy across all the zones of commercial competition from North Africa to the Black Sea. Each went for its rival’s mercantile assets. Genoa sacked Canea on Crete; Venice burned ships at Famagusta and Tunis. The Genoese in Constantinople hurled the Venetian

bailo

out of a window and massacred so many merchants ‘that it has become necessary’, reported back a contemporary, ‘to dig huge deep trenches everywhere to bury the dead’. When this news reached the lagoon, the cry went up: ‘War to the knife!’ Ruggiero Morosini, ominously nicknamed Malabranca (the Cruel Claw), was despatched with a fleet to gut the Genoese colony of Galata while its inhabitants cowered behind the walls of Constantinople and dragged the Byzantines into the fight. A Venetian fleet advanced into the Black Sea and ransacked Caffa, but stayed too long and got iced in. A Genoese squadron got as far as the Venetian lagoon and attacked the town of Malamocco; the Venetian privateer Domenico Schiavo forced his way into Genoa’s harbour,

where he was said to have coined gold ducats on the city’s breakwater as a calculated insult. The war was conducted beyond the point of tactical reason and was immensely damaging to both parties. When the pope attempted to arbitrate and even offered to meet half the costs of the Venetian claims personally, the Republic was seized by irrational emotions and refused.

Both sides were able to put out substantial fleets at great cost. None equalled the ostentatious but futile Genoese display of 1295, when they despatched 165 galleys and thirty-five thousand men. It would be three hundred years before the Mediterranean would see such a show of maritime force again, but the Venetians evaded it and the armada was forced to slink home. In 1298, when the two finally met off the island of Curzola in the Adriatic, 170 galleys were involved. It was the largest maritime battle the republics ever fought. This time the Genoese won a startling victory: only twelve of Venice’s ninety-five galleys survived; five thousand prisoners were captured. Andrea Dandolo, the Venetian admiral, shamed beyond indignity at the prospect of being led through Genoa in fetters, beat his brains out against the gunwales of a Genoese ship. Yet it was a hollow victory too. So many Genoese died at Curzola that when the victorious admiral, Lamba Doria, stepped ashore at Genoa, he was met by silence – no rejoicing crowds, no church bells. The people just mourned their dead. And it would be Venice that gained the posthumous glory. Among those Venetian prisoners unloaded at Genoa was a wealthy merchant who had got up a galley at his own expense. The Venetians mockingly called him Il Milione – the teller of a million tales. Ensconced in some comfort as a rich man, he struck up friendship with another prisoner, Rustichello da Pisa, a writer of romances. As Il Milione started to talk, Rustichello spotted a business opportunity. He took up his pen and began writing. Marco Polo had time to talk himself back down the Mongol highway all the way to China. The gold, the spices, the silk and the customs of the furthest Orient, as well as the tall stories, were transmitted to a fascinated European audience.

One year after Curzola both sides were led sullenly back to the negotiating table. The Peace of Milan in 1299 solved nothing. Its terms left the matter of the Black Sea unresolved. The search for food and raw materials from its shores, the access to the trade routes of central Asia, intensified the unofficial war. The Venetians worked hard to build their position; the Genoese to shoulder them out. Through diplomacy and patience, Venice slowly gained footholds. On the Crimean peninsula the two republics confronted each other across a distance of forty miles; the Venetians at Soldaia, the Genoese at the much more powerful commercial hub at Caffa. It was an unequal contest. The Genoese had absolute control of Caffa; it was a well-fortified city whose magnificent harbour, according to the Arab traveller Ibn Battuta, contained ‘about two hundred vessels in it, both ships of war and trading vessels, small and large, for it is one of the world’s most celebrated ports’. The Genoese worked to smother the Venetian upstart at Soldaia. In 1326 Soldaia was sacked by local Tatar lords beyond Mongol control and abandoned. On the southern shores, the republics competed more directly at Trebizond – the roadhead of the second path to the Orient, via the land route to Tabriz and the Persian Gulf. Here, as at Acre, they occupied adjacent barricaded colonies by permission of the Greek emperor of the tiny kingdom and could stoke up a healthy hatred.

Venice worked to ratchet up the pressure on the northern shore. In 1332 its ambassador, Nicolo Giustinian, journeyed across the winter steppes to the Mongol court at Saray to request an audience with the khan of the Golden Horde. Approaches to the Mongol overlords were occasions of trepidation: Venetian state registers reported ruefully on the lack of volunteers. The khan was a Muslim – ‘the exalted Sultan Muhammad Uzbeg Khan’, Ibn Battuta titled him,

exceedingly powerful, great in dignity, lofty in station, victor over the enemies of God … his territories are vast and his cities great … [he holds audience] in a pavilion, magnificently decorated, called the Golden Pavilion … constructed of wooden rods covered with plaques of gold, and in the centre of it is a wooden couch covered with plaques of silver gilt, its legs being pure silver and their bases encrusted with precious stones. The sultan sits on this throne.

Bowing low before the khan, Giustinian presented his suit. He had come to beg the khan to allow the establishment of a trading colony and to grant commercial privileges at the settlement of Tana on the Sea of Azov – the small, shallow offshoot in the north-west corner of the Black Sea, shaped like its miniature replica.

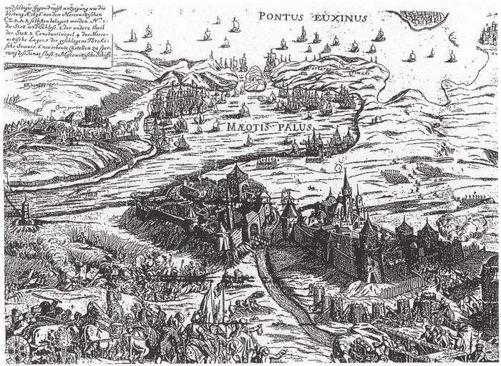

Tana and the Sea of Azov – a later print

Here, where the River Don reaches the sea through a wide marshy delta, the Venetians hoped to regain an effective presence in the Russian and oriental trade. Tana was well situated at the heart of the western Mongol kingdom, ideally placed for journeys north to Moscow and Nizhni Novgorod, the river routes of the Don and the Volga, and at the very head of the great trans-Asian silk route: ‘The road you travel from Tana to Cathay is perfectly safe, whether by day or by night,’ the Florentine

merchant Francesco Pegolotti assured the readers of his merchant’s handbook a few years later. The Mongols were not uninterested in trade with the west and the great khan granted the request. In 1333, the year of the monkey, he gave the Venetians a site on marshy ground beside the river with permission to build stone houses, a church, warehouses and a palisade.

In many respects Tana was better placed than the powerful Genoese centre at Caffa, 250 miles to the west and located on the spur of the Crimean peninsula. Genoa maintained a colony at Tana too but it was subsidiary to its powerful hub, and it certainly had no wish to see Venice develop a foothold. The Venetians also had particular advantages in exploiting this new opportunity. The Sea of Azov was familiar terrain – an estuarine lake with a mean depth of eight metres, whose channels and hidden shoals made navigation difficult; the lagoon-dwelling Venetians with their shallow-draughted galleys managed to nose their way up to Tana with greater ease than the Genoese in their heavier ones. According to the Florentine chronicler Matteo Villani, ‘the Genoese could not go to the trading post at Tana in their galleys as they did at Caffa, to where it was more expensive and difficult to get spices and other merchandise overland than to Tana’. From the start, Tana was a thorn in Genoese flesh – an intrusion into their zone of private monopoly. It became a cornerstone of Genoa’s policy to dislodge Venice from the northern shores of the Greater Sea: ‘there shall be no voyages to Tana’ was the mantra of their diplomacy. The Venetian response was equally robust. According to treaty, the Black Sea was common to all and they intended, as the doge roundly declared in 1350, ‘to maintain free access to the sea with utmost zeal and the employment of all their powers’. Out of this collision of interests would come two more bloody wars.

At Tana a small core of resident Venetian merchants established themselves to manage the hinterland trade across the Russian steppe and the luxury exchanges with the distant East. Marco Polo, from the perspective of his vast, fifteen-year journey to the

Pacific, could afford to treat the Black Sea with disdain as being almost on the doorstep of Venice. ‘We have not spoken to you of the Black Sea or the provinces that lie around it, although we ourselves have explored it thoroughly,’ he wrote. ‘It would be tedious to recount what is daily recounted by others. For there are so many others who explore these waters and sail upon them every day – Venetians, Genoese, Pisans – that everybody knows what is to be found there.’ Yet to the resident consul and his merchants it was the outermost rim of the Venetian world. It felt like an exile. Educated Venetians, watching ice freeze up the shallow alluvial sea for another winter, hunkering down in their ermine furs and squinting into the blizzards being swept on the thousand-mile winds, might have longed for the lights of Venice reflected in their domestic canals.

A note of homesickness, frequent in merchant reports from beyond the Stato da Mar, haunts their letters. It was a three-month round trip for the great merchant fleets from the mother city that set out in spring, touched Tana for a mere few days and vanished again. They left the residents to the vastness of the steppes, watching the nomads moving from horizon to horizon in long processions beyond their settlement, as the merchant Giosafat Barbaro did:

First, herds of horses by the [hundreds]. After them followed herds of camels and oxen, and after them herds of small beasts, which endured for the space of six days, that as far as we might see with our eyes, the plain every way was full of people and beasts following on their way … and in the evening we were weary of looking.

Chronic insecurity was the lot of all Venetian trading posts perched on foreign soil. The whims of the local potentates had to be continuously appeased by watchful diplomacy, lavish presents – and whatever physical barricades they were permitted to erect. None was more dependent on goodwill than Tana. Unlike the Genoese settlement at Caffa, which was a fortress ringed by double walls, Venetian Tana had no meaningful defence in the early

years beyond a flimsy wooden stockade. It was dependent on the stability of the Golden Horde. The senate viewed Tana as being precariously positioned ‘at the limits of the world and in the jaws of our enemies’. The Venetians walked on eggshells. Cooped up for months close to the detested Genoese, their community was so small that Venice gave unusual permission to grant citizenship to other European merchants. Yet back in Venice, Tana was vividly imagined. It gave its name to the Tana, the rope factory in the state arsenal which used Black Sea hemp in its manufacture. It was Tana too that Petrarch was thinking about as he vicariously shivered from the safety of his writing desk, watching the ships depart for the mouth of the Don and speculating on the fierce commercial energy that impelled the Venetians to such outlandish parts.

What drove them on were the possible returns, the ‘insatiable thirst for wealth’ that baffled the scholarly Petrarch so much. At Tana they acquired both the portable, lightweight, high-value luxury items of the furthest Orient and the bulk commodities and foodstuffs of the steppe hinterland: precious stones and silk from China and the Caspian Sea; furs and skins, sweet-smelling beeswax and honey from the glades of Russian forests; wood, salt and grain and dried or salted fish in infinite varieties from the Sea of Azov. In return they shipped back the manufactured goods of a developing industrial Europe: worked woollen cloth from Italy, France and Bruges; German weapons and iron utensils; Baltic amber and wine. On the opposite shore at Trebizond they accessed raw materials – copper and alum, as well as pearls from the Red Sea, ginger, pepper and cinnamon from the Indies. In all these transactions the trade imbalance was huge – Asia had more to sell than the infant industrial base of medieval Europe could offer in return. It had to be paid for with bars of ninety-eight per cent pure silver; large reserves of European bullion drained away into the heartlands of Asia.