City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (25 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

There was one other highly profitable item in which the Venetian merchants came to deal, although its business was always outstripped by the Genoese. Both Caffa and Tana were active

centres of slave trading. The Mongols raided the interior for ‘Russians, Mingrelians, Caucasians, Circassians, Bulgarians, Armenians and divers other people of the Christian world’. The qualities of the ethnic groups were carefully distinguished – different peoples had different merits. If a Tatar was sold (expressly forbidden by the Mongols and the source of repeated trouble) ‘the price is a third more, since it may be taken as certain that no Tatar ever betrayed a master’; Marco Polo brought back a Tatar slave from his travels. Generally slaves were sold young – boys in their teens (to get the most work out of them), the girls a little older. Some were shipped to Venice as domestic and sexual servants, others to Crete in conditions of plantation slavery, where village names such as Sklaverohori and Roussohoria still record the legacy and origin of this commerce. Or they were sold on in an illicit trade, expressly forbidden by the pope, as military slaves to the Mamluk Islamic armies of Egypt. Candia, on Crete, formed one hub of this secret business, where the final destinations of the ‘merchandise’ were usually suppressed. Most of these Black Sea slaves were nominally Christian.

Pero Tafur recorded the practice at the slave markets in the fifteenth century:

The selling takes place as follows. The seller makes the slaves strip to the skin, males as well as females, and they put on them a cloak of felt, and the price is named. Afterwards they throw off their coverings, and make them walk up and down to show whether they have any bodily defect. The seller has to oblige himself, that if a slave dies of the pestilence within sixty days, he will return the price paid.

Sometimes parents came selling their own children, a practice which affronted Tafur, though it did not prevent him acquiring ‘two female slaves and a male, whom I still have in Cordoba with their children’. Though slaves usually only made up a small portion of a Black Sea cargo, there were cases when whole shipments of human merchandise would be entrusted to the holds in a manner similar to that of the later Atlantic slave trade.

To the Republic, Tana mattered hugely. ‘From Tana and the Greater Sea,’ a Venetian source wrote, ‘our merchants have gained the greatest value and profit because they were the source of all kinds of goods.’ For a time merchants there could monopolise almost the entire China trade. The Tana convoys were intricately interlocked with the rhythm of the returning galleys from London and Flanders four thousand miles away, so that they could carry Baltic amber and Flemish cloth to the Black Sea and return with rare oriental goods for Venice’s winter fairs. Exotic produce from the Orient added weight to Venice’s reputation as the market of the world, the one place where you might find anything. For at least a hundred years foreign merchants – particularly Germans – had been coming to Venice in large numbers, bringing metals – silver, copper – and worked cloth to buy these oriental goods.

From the fruits of the long boom of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Venice was transforming itself. By 1300 all the separate islets had been joined by bridges to form a recognisable city, which was densely inhabited. The streets and squares of beaten earth were progressively paved over; stone was replacing wood for building houses. A cobbled way linked the centres of Venetian power – the Rialto and St Mark’s Square. An increasingly wealthy noble class constructed for themselves astonishing palazzos along the Grand Canal in the Gothic style, tempered with elements of Islamic decoration to which the travelling merchants had been exposed in Alexandria and Beirut. New churches were built and the skyline punctuated with their brick campaniles. In 1325 the state arsenal was enlarged to meet the increased requirements for maritime trade and defence. Fifteen years later work was begun redeveloping the doge’s palace into the masterpiece of Venetian Gothic, a delicate traceried structure of astonishing lightness and beauty that seemed to express the effortless serenity, grace, good judgement and stability of the Venetian state. The facade of the basilica of St Mark was gradually transformed from plain Byzantine brick into a rich fantasy of

marble and mosaic, incorporating the plunder of Constantinople and the East, and topped with domes and oriental embellishment that took the viewer halfway to Cairo and Baghdad. Some time around 1260 the horses of the Constantinople hippodrome were winched into place on its loggia as a statement of the city’s new-found self-confidence. Out of maritime trade, Venice was starting to dazzle and bewitch.

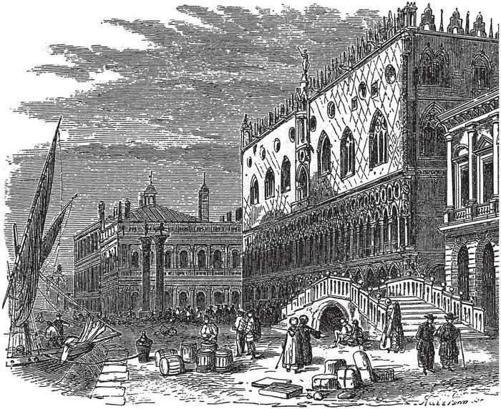

Venetian gothic: the doge’s palace and the waterfront

Meanwhile in the Black Sea the Venetians at Tana began to steal a march on Genoese Caffa. The state registers bear running testament to the close attention paid to their trading post. After permission for a settlement was granted in 1333, a consul was immediately despatched who ‘is allowed to trade’ – an unusual concession – ‘and must keep in his service a lawyer, four servants and four horses’. In 1340 he was instructed to seek another abode because of the closeness to the Genoese and the frequent fights; ambassadors were sent back to Uzbeg Khan for the purpose. The

consul was later barred from trading but his salary rose in recompense. The behaviour of the Venetian merchants was often a cause for concern. In the summer of 1343 it was noted that ‘a lot of merchants are fraudulently avoiding the [tax] imposed by the khan. This is not without risk to the colony. The consul will henceforth insist that all merchants swear that they have actually paid.’ Gifts of carefully stipulated amounts were to be presented to the khan. A later curt directive to the consul states that ‘the Venetians must stop taxing the merchandise of foreign merchants: this could displease the Tatar government and end up damaging Venetian interests’. The thin margin between tolerance and xenophobia worried the authorities back in the lagoon.

Despite the careful prescriptions of the Venetian senate the fragile balancing act at Tana collapsed. In 1341 Uzbeg died. His thirty-year reign had been the longest and most stable Mongol administration. Venice was quick to analyse the dangers: ‘The death of Uzbeg exposes the trading post at Tana to difficult days; the consul will choose twelve Venetian merchants to consider the new circumstances and make obeisance to the new [khan].’ This model diplomacy was almost immediately undone – as so often in Venetian trading posts – by the ill-discipline of an individual merchant. It came against the usual brawling rivalry between Venetian and Genoese residents in confined places – men were killed in these contests – which irked the local Tatar governor, unable to tell the two groups of citizens apart. There were other matters too: the tax evasion, the failure to give adequate presents, the accustomed arrogance of the unruly foreigners. Venetian self-confidence was particularly high in September 1343 when armed galleys put in at the mouth of the Don. A personal altercation led to an eruption of violence. An important local Tatar, Haji Omar, apparently struck a Venetian, Andriolo Civrano, in a dispute. Civrano’s response was premeditated: he ambushed Haji Omar at night and killed him along with several members of his family. Aghast, the Venetian community braced itself and tried to return the body and pay blood money. First they called on the

Genoese to take a united stance in confronting the crisis. The Genoese did no such thing. They attacked and plundered Tatar property themselves and sailed away, leaving the Venetians to face the consequences. In the ensuing violence, sixty Venetians were killed. The new khan, Zanibeck, descended on Tana and sacked it, destroyed all their goods and took some of the merchants hostage. The survivors fled to Genoese Caffa in their ships where they begged for safe haven. All contact with the Asiatic world was now concentrated on this Genoese fort.

The crisis at Tana spread. If Zanibeck was irked by the Venetians, he was more deeply so by the Genoese at Caffa, which had become a direct colony outside the khan’s control, taxing other foreign merchants as it pleased. Zanibeck decided to wipe the troublesome Italians from his domain. He descended on Caffa with a large army. It led to a rare moment of Genoese and Venetian co-operation. The Venetians were granted tax-free concessions and they stood shoulder to shoulder behind the city’s impressive defences. Over the icy winter of 1343, the Mongol army bombarded the city’s walls, but the advantage of the sea was with the Genoese. In February 1344 a fleet raised the siege; the Mongols retreated, leaving fifteen thousand dead. The following year Zanibeck was back, more determined than ever to expel the Genoese.

The two rival republics agreed on a joint trade embargo in all the realms of the Mongols. In 1344, the Venetian senate forbade ‘all commerce with the regions ruled by Zanibeck, including Caffa’. The decree was read out on the steps of the Rialto to ensure that the message was clearly understood, with the threat of heavy fines and the forfeit of half the cargo. At the same time, with the agreement of the Genoese, they sent conciliatory ambassadors back to Saray to attempt to resolve the crisis. It was in vain. The only response was the whipping flight of Tatar arrows over the city walls, the tensioning creak and thunder of catapults. The siege of Caffa went on into 1346.

By the 1340s the Black Sea had become the warehouse of the world. The rolling siege of Caffa and the destruction of Tana

brought trade to a standstill, like ice freezing the winter sea. The effects were felt throughout the hungry cities of the Mediterranean basin. There was famine in the eastern Mediterranean – lack of wheat, salt, fish in Byzantium; shortage of wheat in Venice and a rocketing of prices in luxury goods: silk and spices doubled throughout Europe. It was these effects that made the Black Sea so crucial and the competition between the maritime republics so fierce. The returns encouraged the merchants to endure all the difficulties of trade on the edge of the steppe. Coupled with the ongoing papal embargo on the Mamluks, world trade was grinding to a halt. There was now no outlet in the East for the manufactured goods of Italy and the Low Countries. In 1344 the Venetians made an anguished appeal to the pope:

… at this time … the trade with Tana and the Black Sea can be seen to be lost or obstructed. From these regions our merchants have been accustomed to derive the greatest gain and profit, since it was the source of all trade both in exporting our [wares] and importing them. And now our merchants know not where to go and cannot keep employed.

The pope began to permit a gentle relaxation of trade with Egypt and Syria; it was start of a process that would gradually switch the spice trade back to the Mediterranean basin.

But in Caffa the siege took an unexpected turn. The Tatars outside the wall started to die. According to the only contemporary account:

Disease seized and struck down the whole Tatar army. Every day unknown thousands perished … they died as soon as the symptoms appeared on their bodies, the result of coagulating humours in their groins and armpits followed by putrid fever. All medical advice and help was useless. The Tatars, exhausted, astonished and completely demoralised by the appalling catastrophe and virulent disease, realised that there was no hope of avoiding death … and ordered the corpses to be loaded into their catapults and flung into Caffa, so that the enemy might be wiped out by the terrible stench. It appears that huge piles of dead were hurled inside, and the Christians could neither hide, flee nor escape from these corpses, which they tried to dump in the sea, as many as they could. The air soon became completely infected and the water supply was poisoned by rotting corpses.

It is unlikely that the Black Death was transmitted from just this single event, but it was soon carried west on merchant ships. Only four out of eight Genoese galleys sailing the Black Sea in 1347 made it back to the city; on the others all the crew died and the ships vanished. The plague was in Constantinople in December; it reached Venice some time around January 1348, almost simultaneously with a series of portentous earthquakes which set all the church bells ringing and sucked the water out of the Grand Canal. By March plague had Venice in its grip; by May, as the weather warmed up, it was out of control. No city on earth was more densely populated. It now faced catastrophe. According to the Venetian chronicler Lorenzo de Monacis, the plague exceeded all proportions:

[It] raged so fiercely that squares, porticoes, tombs, and all the holy places were crammed with corpses. At night many were buried in the public streets, some under the floors of their own homes; many died unconfessed; corpses rotted in abandoned houses … fathers, sons, brothers, neighbours and friends abandoned each other … not only would doctors not visit anyone, they fled from the sick … the same terror seized the priests and clerics … there was no rational thought about the crisis … the whole city was a tomb.

It became necessary to take the bodies away at public expense on special ships, called pontoons, which rowed through the city, dragging the corpses from the abandoned houses, taking them … to islands outside the city and dumping them in heaps in long, wide pits, dug for the purpose with huge effort. Many of those on the pontoons and in the pits were still breathing and died [of suffocation]; meanwhile most of the oarsmen caught the plague. Precious furniture, money, gold and silver left lying about in the abandoned houses were not stolen by thieves – extraordinary lethargy or terror infected everyone; none seized by the plague survived seven hours; pregnant women did not escape it: for many, the foetus was expelled with their innards. The plague cut down women and men, old and young in equal measure. Once it struck a house, none left alive.