City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (29 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

The news reached Venice on 4 June. Its arrival was recorded in a memorable letter written by Petrarch.

It was about midday … I was standing by chance at a window looking at the wide expanse of sea … suddenly we were interrupted by the unexpected sight of one of those long ships they call galleys, all decorated with green foliage, which was coming into port under oars … the sailors and some young men crowned with leaves and with joyful faces were waving banners from the bow … the lookout in the highest tower signalled the arrival and the whole city came running spontaneously, eager to know what had happened. When the ship was near enough to make out the details, we could see the enemy flags hanging from the stern. There was no doubt that the ship was announcing a victory … When he heard this Doge Lorenzo … together with all the people wanted to give heartfelt thanks to God throughout the whole city but especially in the basilica of St Mark, which I believe is the most beautiful church there is.

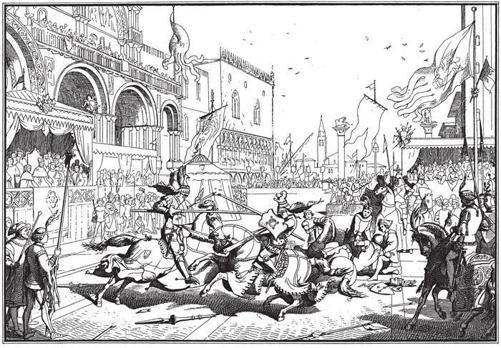

There was an explosion of festive joy within the city. Everyone understood how much Crete mattered. It was the hub of the whole colonial and commercial system, on which Venice depended for trade and wealth. There were church services and processions to give thanks for the victory, and expressions of civic generosity. Convicts were released from prison; dowries allotted to poor servant girls; the whole city, according to de Monacis, was given over to days of ceremonial and spectacle. Petrarch watched tournaments and jousting in St Mark’s Square, sitting beside the doge on the church loggia under an awning with the four horses breathing down his neck:

… they seemed to be neighing and pawing the ground as if alive … below me there wasn’t an empty spot … the huge square, the church itself, the towers, roofs, porticoes and windows overflowed with spectators jammed together, as if packed one on another … On our right … was a wooden stage where four hundred of the most eligible noble women, the flower of beauty and gentility, were seated.

Celebrations after the recapture of Crete

There was even a visiting party of English noblemen present to enjoy the proceedings.

With victory came retribution. The senate was determined to eradicate the guilty parties from its domain. Punishment came with many refinements: death by torture or decapitation; the tearing apart of families; the exile not just from the island of Crete but from ‘the lands of the emperor of Constantinople, the duchy of the Aegean, the Knights of St John on Rhodes, the lands of the Turks’. Venice sought to expunge Cretan branches of families such as Gradenigo and Venier from its records. For home consumption, some were brought back to Venice in chains. Paladino Permarino had his hands chopped off and was hanged between the twin columns as an inspiration and a warning.

*

Both celebration and exemplary punishment proved to be premature. The towns of Crete had been restored to fealty; in the countryside the embers of revolt kept bursting into flames that proved hard to stamp out. In the mountains of western Crete a small rump of dissident Venetian rebels, including Tito Venier, one of the original ringleaders, joined forces with the Greek clan of Callergis, backed by a truculent peasantry, to continue guerrilla warfare against the Venetian state. They targeted isolated farms, killing their occupants, burning their vineyards, destroying fortified positions so that Venetian landlords were forced back into the towns and the countryside became a zone of insurrection and danger; small military detachments were ambushed and wiped out. Venice had to devote increasing numbers of men and rotate their military commanders in a search for closure. It was a dirty, protracted war eventually won by cruelty and perseverance. It took four years. The Venetians employed a scorched-earth policy, backed by rewards for turning in rebels. As the Greek peasants starved, they began to co-operate, handing over captured rebels, their wives and children – and sacks of bloody heads. With their support base shrinking, the rebels were forced further and further back into the inaccessible recesses of mountain Crete. In the

spring of 1368, Tito Venier and the Callergis brothers made a last stand at Anopoli, the most remote fastness in the south-west. Patiently they were tracked down by the Venetian commander and betrayed by the local populace. In a cave on a rocky hillside, Cretan resistance lived its final moments. Holed up and surrounded, Giorgio Callergis continued to fire defiant arrows at the Venetian soldiers, but his brother realised that further resistance was pointless. In a symbolic act of defeat, he broke his bow, saying that it was no longer needed. Venier, wounded in the ear, stumbled out to surrender. When he asked for a bandage, someone replied: ‘Your wound doesn’t need treatment; it’s utterly incurable.’ Venier realised what was being said and just nodded. Shortly afterwards he was beheaded in the public square in Candia.

Crete, exhausted and ruined, sank back into peace. There would be no further major rebellions. The Venetian lion would fly from the duke’s palace in Candia for another three hundred years; the Republic ruled it with an iron hand. Those areas that had provided centres of rebellion, the high, fertile upland plateau of Lasithi in the east, Anopoli in the Sphakian mountains, were desertified. Cultivation was forbidden on pain of death. They remained in this state for a century.

In all this turmoil, Genoa stayed its hand. When the rebel galley reached the city in 1364 and begged for aid, it was refused. Venice had sent ambassadors to request a united front against rebellion; Genoa probably resisted the temptation more because the pope had demanded Catholic unity than because of any active spirit of co-operation between the two rivals. It was only a temporary ceasefire. Five years after the final surrender war broke out yet again.

Bridling St Mark

1372–1379

The trigger was ominously familiar: the presence of rival merchants in a foreign port, then an exchange of words, a scuffle, a brawl, finally a massacre. The difference lay in the outcome – where previous wars had ended in uneasy truce, the resulting contest was fought to the finish. In the last quarter of the fourteenth century both sides went for the jugular. The War of Chioggia, as it is known to history, brought together all the choke points of commercial rivalry – the shores of the Levant, the Black Sea, the coasts of Greece, the troubled waterways of the Bosphorus – but it was decided within the Venetian lagoon.

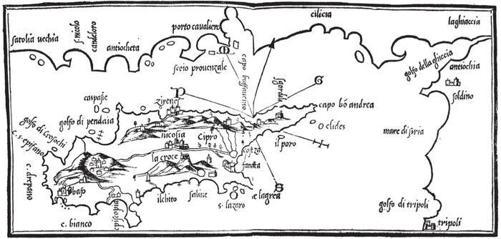

The flashpoint was the port of Famagusta. Cyprus, ruled by a fading dynasty of French crusaders, the Lusignans, was a crucial trading hub for both republics. Venice had strong commercial interests there in cotton and sugar growing, and the island was a market for the exchange of goods and a way station on the route to the Levant. Famagusta, lying among palm trees beside a glittering sea, was only sixty miles from Beirut. Here, at the coronation of a new Lusignan king, Peter II, the jostling rivalries of Venice and Genoa suddenly exploded. The issue was petty precedence. The Venetians seized the reins of the king’s horse as he was led to the cathedral; at the subsequent banquet a dispute broke out as to which consul should have the honoured place at the king’s right hand. The Genoese started throwing bread and meat at their hated rivals, but they had also come with concealed swords. The Cypriots turned on them and hurled their consul out of a window, then descended on the Genoese quarter and ransacked

it. For Genoa this was an insufferable insult. The following year a substantial fleet descended on the island and seized it.

The Venetians were not expelled from Cyprus but this turn of events ratcheted up the tension. It made them strategically anxious. They were in danger of being squeezed out of crucial trading zones. This feeling was soon compounded by affairs back in Constantinople, where the Italian republics were meddling furiously in the interminable dynastic struggles for the Byzantine throne. They had become rival kingmakers in the city. Venice supported the emperor, John V Palaeologus; the Genoese backed his son Andronicus.

Cyprus

Both acted with ruthless self-interest. Venice was particularly keen to maintain its access to the Black Sea, which Genoa continued to dominate. When John visited the city in 1370, they held him prisoner for a year over an unpaid debt. Six years later they demanded the island of Tenedos with menaces – a war fleet in the Bosphorus – in return for his crown jewels, which they held in hock. Tenedos, a small rocky island off the coast of Asia Minor, was strategically critical; twelve miles from the mouth of the Dardanelles, it surveyed the straits to Constantinople and beyond. As such it was ‘the key to the entrance for all those who wanted to sail to the Black Sea, that is Tana and Trebizond’. The Republic wanted it as a throttle on Genoese sea traffic.

The emperor surrendered the island. Genoa’s reply was equally prompt. They simply deposed him, replaced him with his son and demanded the island back. However, when they despatched their own fleet to claim their prize, they were met with a forthright response. The Greek population sided with the Venetians and refused; the intruders were repelled. Andronicus arrested the Venetian

bailo

in Constantinople. Venice demanded the release of their officials and restitution of John V, now lingering in a gloomy dungeon on the city walls. On 24 April 1378 the Republic declared war.

The fleets that both sides could put out were still small in the long shadow of the Black Death. What amplified the contest were the terrestrial allies that the maritime rivals could now enlist. Venice was increasingly involved in the complex power politics of the city states of Italy. For the first time, the Republic had not only a

stato da mar

but also a modest

stato da terra

– holdings of land on mainland Italy, centred on the city of Treviso sixteen miles to the north. From the surrounding area, the Trevigiano, the city derived vital food supplies, floated down the River Brenta to the Venetian lagoon near the town of Chioggia. Three great rivers, the Po, Brenta and Adige, whose alluvial deposits, drawn out of the distant Alps, had formed the Venetian lagoon, debouched into the sea near this strategic point. These waterways, along with an interconnecting web of cross-canals, were the arterial trade routes into the heart of Italy, and Venice guarded them all at their point of exit. The Republic was able to apply vice-like economic pressure on northern Italy, controlling salt supplies, taxing river traffic, pushing its own goods upstream on the slow waters in flat-bottomed boats under monopoly conditions. To its immediate neighbours – Padua to the west, the king of Hungary to the east, nervous for his control of the Dalmatian coast – Venice was too powerful, too rich, too proud. If the Republic was a source of admiration, it also evoked envy and fear. The letters that passed between Genoa, Padua and Hungary voiced the profound disquiet ‘that if [the Venetians] were allowed to establish a firm foothold

on the Italian mainland, as they had on the sea, they would in a short time make themselves lords of all Lombardy, and finally of Italy’. Genoa, Francesco Carrara, lord of Padua, and Louis, king of Hungary, signed a pact to encircle Venice by land and sea ‘for the humiliation of Venice and all her allies’.