City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (32 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

Within the city the bell was rung to call the popular assembly to hear the response. The gathered crowd was now given an unvarnished account of their plight. A year earlier, Genoa’s defeat at the sea battle of Anzio had nearly torn that city apart. This was to be a similar test of Venice’s character, its patriotism and class coherence. The mood was initially resolute. They would go down fighting rather than die of starvation: ‘Let us arm ourselves; let us equip and mount what galleys are in the arsenal; let us go forth; it is better to perish in the defence of our country than to perish here through want.’ Everyone prepared for sacrifices. There was to be universal conscription. Salaries of magistrates and state officials were suspended; new patriotic state loans were demanded; business and commerce were abandoned; property prices fell to a quarter of their previous value. The whole city was mobilised in a desperate bid for survival, so that its bronze horses, looted in their turn from Constantinople, could continue to paw the humid Venetian air unfettered. Emergency earthworks were hastily thrown up on the Lido of St Nicholas; a ring of palisades erected in the shallow water around the city; armed boats ordered to patrol the canals night and day; signal arrangements redefined. The arsenal set to unceasing work, refitting mothballed galleys.

Yet this show of patriotic unity under the banner of St Mark concealed dangerous fault lines. At the point of sacrifice the unbearable haughtiness of the noble class stuck in the popular

gullet. The people wanted to be led by commanders who shared the same conditions and dangers. The crews declared they would not now man the new trenches on the Lido of St Nicholas unless the nobles went too, and the appointment of Taddeo Giustinian as commander of the city’s defences brought the city to the edge of revolt. He was evidently detested; there was only one man they would accept. ‘You want us to go in the galleys,’ went up the cry in St Mark’s Square, ‘give us our Captain Pisani! We want Pisani out of prison!’ The crowd grew in strength and became increasingly vocal in their disapproval. According to popular hagiography, Pisani could hear the cries from the ducal prison. Putting his head to the bars, he called out ‘Long live St Mark!’ The crowd responded with a throaty roar. Upstairs in the senatorial chamber a panicky debate was underway. The crowd put ladders to the windows. They hammered the chamber door with a rhythmic refrain: ‘Vettor Pisani! Vettor Pisani!’ Thoroughly alarmed, the senate caved in: the people would be given Pisani. It was now the end of a nerve-racking day, but when Pisani was told of his release he placidly replied that he would prefer to pass the night where he was, in prayer and contemplation. Release could wait for the morrow.

At dawn on 19 August, in one of the great popular scenes from Venetian history, the unshackled Pisani stepped free from prison to the roar of the crowd. Hoisted onto the shoulders of the galley crews with people climbing up onto ledges and parapets to get a glimpse of the hero, raising their hands to the sky, shouting and cheering, he was carried up the steps of the palace and delivered to the doge. There was an immediate reconciliation; a solemn mass. Pisani played his part carefully, pledging himself humbly to the Republic. Then he was again raised aloft on the shoulders of the crowd and carried away to his house.

It was an exhilarating moment, but also a dangerous one. It was only twenty-four years since a doge had been beheaded for an attempted coup and Pisani was wary of personal adulation. On his way home, he was stopped by an old sailor who stepped

forward and called out in a loud voice, ‘Now is the time to avenge yourself by seizing the dictatorship of the city. Behold, all are at your service; all are willing at this very moment to proclaim you prince, if you choose!’ Pisani turned and dealt the man a stinging blow. Raising his voice, he called, ‘Let none who wish me well say “Long live Pisani!” – rather, “Long live St Mark!”’

In fact, the senate, piqued by this popular revolt, had been more grudging with their favours than the crowd at first understood. Pisani was not appointed captain-general, only commander of the

lido

defences. The crews were still ordered to report to the detested Taddeo Giustinian. When this fact sank in there was a further wave of popular dissent. They threw down their banners and declared they would rather be cut to pieces than serve under Taddeo. On the 20th the senate caved in again. Pisani was declared overall commander of the city’s defence. At an emotional service in St Mark’s he vowed to die for the Republic.

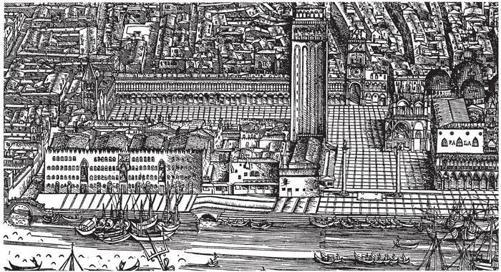

The waterfront at St Mark’s. Recruiting benches were set up on the Molo – the quayside in front of the two columns

The confirmed appointment had a galvanic effect on morale. The following day the customary recruiting benches were set up near the two columns; the scribes could not enter the names of volunteers fast enough. Everyone enrolled: artists and cutlers, tailors and apothecaries. The unskilled were given rowing lessons in

the Giudecca Canal; stone fortifications were erected by masons on the Lido of St Nicholas at lightning speed; thirty mothballed galleys were re-equipped; palisades and chains encircled the city and closed the canals; every sector of the city’s defences was detailed to particular officers. They were to be manned night and day. Many gave their savings to the cause; women plucked the jewellery from their dresses to pay for food and soldiers.

None of this was a moment too soon. In darkness on 24 August Doria mounted a two-pronged attack. One force attempted a galley landing on the Lido of St Nicholas. A second pushed in a swarm of light boats to attack the palisades that protected the city’s southern shore. Both were beaten back, but the defenders were compelled to abandon other towns along the

lidi

. Doria established himself at Malamocco, from where he could bombard the islands of the southern lagoon. The red-and-white flag could be seen from the campanile of St Mark’s.

Venice was almost completely cut off; there was now just one land route by which it could receive supplies. The sea was sealed. Yet the balance had shifted slightly. Doria had missed a moment. If he had struck out for Venice as soon as Chioggia fell, the city must have capitulated. The brief hesitation had allowed Pisani to regroup and the failure on the 24th gave Venice brief hope. The lord of Padua, disgusted by the failure to force home the advantage, politely took his troops off to the siege of Treviso. Doria decided on attrition. He would starve Venice to death. With winter coming on he withdrew his men from the

lidi

back to Chioggia. Within Venice, supplies started to run low; desperate schemes were proposed to abandon the city and emigrate to Crete or Negroponte. They were instantly rejected. Patriotic Venetians declared that ‘sooner than abandon their city, they would bury themselves under her ruins’.

Fight to the Finish

AUTUMN 1379–JUNE 1380

Slowly, relentlessly, Venice was being squeezed dry because ‘the Genoese held [the city] locked tight, both by sea, and by land from Lombardy’. As autumn wore on the price of wheat, wine, meat and cheese rose to unprecedented levels. Attempts at replenishment proved disastrous; eleven light galleys loading grain further down the coast were caught and destroyed. The strain of guarding the palisades by night and day, waiting for the ringing of church bells, serving in the trenches on the Lido as the weather worsened, all started to take their toll. The Genoese meanwhile continued to receive plentiful provisions down the river routes from Padua. But after the eruption of popular anger at the fall of Chioggia, the patricians realised that it was in their better interest to take regard for the suffering of the poor. ‘Go,’ the people were told, ‘all who are pressed by hunger, to the dwellings of the patricians; there you will find friends and brethren, who will divide with you their last crust!’ A fragile solidarity persisted.

The only hope of relief was the return of Zeno, still far over the horizon. In November it was learned he was off Crete, after months of plundering Genoese shipping on a wide track between the coast of Italy and the Golden Horn. Yet another ship was despatched with all haste to call him back. Knowledge of his whereabouts raised a small hope.

Pisani’s seamen attempted to damage Doria’s supply chain. They used their knowledge of the inner lagoon, its creeks and secret channels, sandbanks and reed beds, to intercept the supply

boats coming down the Brenta. With information passed by spies within Chioggia, teams of small boats probed the shallows, lying low at twilight to catch unwary merchants delivering grain or wine. Near the Castle of the Salt Beds, the beleaguered Venetian outpost close to Chioggia, they ambushed sufficient boats to force the Paduans to supply armed escorts, and to discourage merchants from making the voyage. They also had the advantage over the deep-draughted Genoese galleys, uncertain of the channels and liable to grounding if the water was low or they missed their way. Watching the movement of these ships closely, ambitious plans were made to trap isolated vessels, like hunters trying to down an elephant. Lying up at evening in the reed beds, using the cover of the fog and closing night to surprise a foe unable to manoeuvre, landing detachments of archers to shoot from the shelter of the clustering trees, setting fire to the reeds to confuse and obscure, taking short cuts to head off their prey, darting out from nowhere in rowing boats to the sudden blaring of trumpets and drums, they began to play on their enemy’s nerves. They had an emboldening success when they cornered and destroyed an enemy galley, the

Savonese

, and captured its noble commander.

It was a small triumph which had disproportionate effects on morale. Upping the stakes, Pisani attempted to snare three galleys on their way to bombard the Castle of the Salt Beds, but the plan was spoiled when the ships spotted the soldiers’ banners behind the reeds. Back-paddling furiously and under a bombardment of missiles from the banks, they slipped away. And Pisani had his outright failures; trying to reconnoitre Chioggia’s defences with increasing curiosity, he lost ten small boats and thirty men, including the doge’s nephew killed in the skirmish. But his close observation of the position of the enemy and the entrances and exits of the lagoon convinced him of the possibility of a daring strike. The disparity between the two forces was huge. The enemy had thirty thousand men, fifty galleys, between seven and eight hundred light boats, ample food supplies,

access to timber, gunpowder, arrows, crossbow bolts. But they also had one hidden weakness, which he was certain they had not foreseen.

Some time in late autumn he put forward a proposal to the doge and the war committee for positive action. The city had its back to the wall. Zeno’s whereabouts were unknown; the people were wilting both from a lack of hope and a shortage of food; rather than let their morale dwindle to nothing, it was better to die on their feet. The plan was supported by Venice’s hired general, Giacomo de Cavalli. The senate accepted it and, perhaps still mindful of the sailors hammering on the chamber door, published a remarkable decree to harness all the resources of patriotic goodwill of a languishing people. For a hundred years, entry to the Venetian nobility had been closed to newcomers. Now the senate published a proclamation offering to ennoble fifty citizens who provided the most outstanding service to the Republic in its hour of need.

The resulting influx of money, resources and goodwill had a short-term galvanising effect on the mood of the people. The work fitting out the galleys was pushed forward in the arsenal; there was rowing practice in the Grand Canal for the inexpert oarsmen who volunteered for the operation, but it was touch and go. The sharpness of deprivation drove people wailing into the piazza. When would Zeno come? There was fear that any delay could prove fatal to the willpower of the city. It was impossible to wait for the missing fleet, and news from Chioggia that the Genoese and Paduans had fallen out over the distribution of booty suggested that the time was ripe. The old doge declared that he would lead the expedition as captain-general with Pisani as vice-captain.