City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (22 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

The contest at Acre set the tone for a long series of Venetian–Genoese wars – driven by profit but sustained by patriotic fervour and visceral hate. Genoa was bitterly discomfited by the defeat but did not submit. It simply altered its angle of attack; it decided

to use diplomatic methods to strike at the eastern hub of Venetian sea power – Constantinople itself.

*

From the start the Latin Empire of Constantinople had been a sickly creature: starved of long-term supplies of manpower, short of funds, hemmed in by resentful and unassimilated Greeks. By the middle of the century its position was critical. The Latin emperor, Baldwin II, controlled little more than the footprint of the city itself. He was so short of cash that he sold off the copper from the palace roofs and pawned the city’s most precious relic, the crown of thorns, to Venetian merchants – who sold it on to the king of France. Only the Venetians, for whom the city was both a second home and a trading base of enormous value, worked wholeheartedly to sustain Baldwin’s position; the permanent presence of a Venetian fleet in the Golden Horn was the best guarantor of the Latin emperor’s survival. Sixty miles over the water in Asia, the Byzantine emperor in exile, Michael VIII, was biding his time in the lakeside town of Nicaea, when an unexpected Genoese deputation called on him in the autumn of 1260.

The Genoese arrived with a proposition. They offered the emperor the services of their fleets for the reconquest of the city. To Michael this was providential. He knew how weak Baldwin’s position was; he also knew how hard the Latins would be to displace with the Venetian navy unchecked. A deal was hammered out. The Genoese would supply fifty ships, the running costs (for which they set a high price) to be paid by Michael, to win back Constantinople. In return they were to supplant the Venetians in the city with all the tax-free trading rights, land and commercial infrastructure – the quays and warehouses – which their rivals presently enjoyed. Free trade and self-governing colonies were to be granted in a scattering of key trading locations across the Aegean, such as Salonica and Smyrna; they would also become the rightful owners of Venice’s most precious colonies – Crete and Negroponte. So keen was Michael for the deal he also granted

an unprecedented additional favour: access to the trade of the Black Sea, from which the Byzantines had always been careful to exclude Italian merchants. In effect Genoa would supplant Venice in the eastern Mediterranean. The Treaty of Nymphaion, signed on the coast of Asia Minor on 10 July 1261, opened up new imperial prospects for Genoa and a second front in the maritime war.

In the event, the end came fifteen days later without the Genoese firing a shot. On 25 July 1261, the Venetian fleet made a sally up the Bosphorus to attack a Byzantine position; Michael meanwhile despatched a small contingent to study Constantinople’s defences. Inside knowledge informed the raiders of an underground passage and a scalable wall. While Baldwin was asleep in his palace on the other side of the city, a band of men slipped into the city, hurled a few surprised guards off the ramparts and opened the gates. It was so abrupt, so opportunist that Baldwin had to flee to a Venetian merchant ship without his crown and sceptre. By the time the Venetian fleet hurried back to the Golden Horn, they found their whole quarter on fire, their families and their compatriots crowding the waterfront like bees smoked out of their hives, arms outstretched, begging for rescue. Perhaps three thousand were taken off. The refugees, who had lived in the city for generations, watched their lives and their fortunes guttering down to the water’s edge and called out farewells to the city they considered home. Many died of thirst or starvation before the dangerously overcrowded ships reached Negroponte. Back in Venice the news was received with astonishment and dismay. Venice had propped up the Latin Empire for fifty years; its commercial loss was a catastrophe, doubled by the sudden preferment of the hated rival. The Genoese methodically destroyed the Venetian headquarters in Constantinople and shipped its stones home as a trophy to construct a new church to St George. Such national taunts mattered.

The sea war ground on for nine more attritional years. The Venetians won the pitched battles, but found themselves unable to counter Genoese privateers harrying their merchant convoys.

Such hit-and-run tactics were discomfiting and potentially inexhaustible. Venice preferred defined, short sharp wars and a return to peaceful business; for a city dependent on the sea endemic piracy had the potential to inflict grave damage. Underlying this first Genoese war was a profound truth: neither side had the resources to win the sea by conventional means – they could only exhaust themselves in the endeavour. Peace, when it came in 1270, was little more than a truce imposed on embittered foes. The resumption of war was merely a matter of time, but the idea of inflicting a maritime knockout blow was potent: Genoa did just that to Pisa in 1284. It remained the elusive goal of both Genoa and Venice for another century.

*

When the Venetian refugees gazed back at their burning quarter from the choppy waters of the Bosphorus in the summer of 1261 they might have thought that they had seen Constantinople for the last time. It looked too as though the Republic’s imperial and commercial expansion had come juddering to a halt as it braced itself for the Byzantine and Genoese backlash. Genoese merchants hurried back to the city, took over their rivals’ locations and began to exploit the new commercial concessions in the Black Sea.

Yet none of Venice’s worst fears ever quite came to pass. Though Michael unleashed a swarm of privateers across the Aegean, Venice was too deeply entrenched to be dislodged. A few small islands were lost. Crete, Modon–Coron and Negroponte held firm. And the Genoese quickly became as unpopular as ever the Venetians had been; all the Byzantine hauteur about the arrogance and greed of the Italian traders resurfaced: ‘a foreign land peopled by barbarians of the utmost insolence and stupidity’ remained the considered view. Worse still the Genoese were caught plotting for a different reinstatement of a Latin empire within the city. The Genoese, in their turn, were temporarily banished, then reinstated – but this time outside the city walls. They were granted a separate settlement across the Golden Horn in the suburb of Galata –

and the Venetians were allowed back into Constantinople in 1268 with a resumption of permitted trading rights and equal access to the Black Sea. The two troublesome republics were to be kept physically apart and played off against each other.

It was a typical piece of Byzantine diplomacy but it concealed an uncomfortable fact. The Treaty of Nymphaion, signed with the Genoese in 1261, would prove to be a stepping stone to disaster. By overtly recognising the need for Italian naval support, allowing the Genoese an autonomous, fortified settlement at Galata and throwing open the Black Sea to foreign trade, Byzantium’s key prerogatives were given away and its naval power progressively undermined. Twenty years later, the emperor Andronicos disbanded the Byzantine fleet altogether as a cost-cutting measure. Henceforward Venice and Genoa would usurp naval control over her seas, ports, straits, grain supplies and strategic alliances. The war between the two republics would be fought in the Bosphorus, beneath the walls of Galata, in the Black Sea and the shores of the Golden Horn, while the Byzantine emperors watched helplessly from behind their walls or were dragged in as hapless pawns. The enmity between the maritime republics would remain a malign force within Constantinople to the very last day of its Christian life, and it muffled the stealthy advance of another emergent power in the region – the Turkic tribes now moving west across the land mass of Asia Minor.

In the city’s hippodrome there was a remarkable column, erected by Constantine the Great at the city’s founding eleven hundred years earlier. Even then it was ancient. It had once stood in the temple of Apollo at Delphi as a monument to Greek freedom, commemorating the defeat of the Persians at the battle of Plataea in 479

BC

; it was said to have been cast from the shields of the Persian dead. The bodies of three intertwined serpents formed a tightly coiled column cresting into flaring heads, finely worked in polished bronze. After 1261, the intertwined creatures might as well have represented, not freedom, but entanglement, the serpent head of the Byzantine Empire hopelessly intertwined with

those of Genoa and Venice in an embrace from which henceforth it could never extricate itself.

The game that was now being set out across the waters and shores of the Byzantine Empire was being played for high stakes. Venice and Genoa were involved in a contest for both survival and wealth. By the thirteenth century Europe was in the middle of a long boom from which the Italian maritime republics were uniquely placed to profit. Between classical times and 1200 no western city had a population that surpassed twenty thousand. By 1300 there were nine cities in Italy alone of more than fifty thousand. Paris swelled from twenty thousand to two hundred thousand in a century; Florence had 120,000 by 1320, Venice a hundred thousand, fed by immigration from the Dalmatian coast. The population of northern Italy was immense. It would continue to climb until an ominous day some time in early 1348 when an unknown ship from the Black Sea tied up near Petrarch’s house in the Basin of St Mark. It would not be surpassed again until the eighteenth century.

Italian urban centres such as Milan, Florence and Bologna were unable to feed themselves, no matter how closely they dredged the agricultural resources of the Po valley. Like ancient Rome, the growing metropolises depended on the import of food by sea. Genoa and Venice were now poised to dominate its provision. Venice, the landless city which had always lived solely on import, had an unsurpassed understanding of food supply. It was as dense as any city on earth; by 1300 almost all available land had been built on; the islands had been linked by bridges. Hunger like the threat of the sea was a constant. The records of the various Venetian governing bodies reveal a near obsession with grain. The orders, the prices, the quantities, the damping down or increase of supply are monotonous but crucial entries in the state registers. Grain not only preserved the serenity of the city, but the

biscotto

– literally the ‘double-cooked’ long-lasting dry ship’s biscuit – was the carbohydrate that powered the merchant galleys and war fleets without which it could not be secured. Venice

had an office for grain, as it did for other staples, whose activities were scrupulously regulated as a matter of national security. Grain officials had to report every month to the doge on the city’s stocks, which were subject to delicate controls. (It was a fine balance – if levels were too low, the want would be felt; too high, grain prices would fall, inflicting losses on the Commune.) After 1260 with the inexorable rise in the populations of both Genoa and Venice, the competition for grain would spill over into the contested waters of the Byzantine world. In other commodity foodstuffs – oil, wine, salt, fish – Venice and Genoa had the opportunity to profit as critical middlemen to the clamouring markets on their doorsteps.

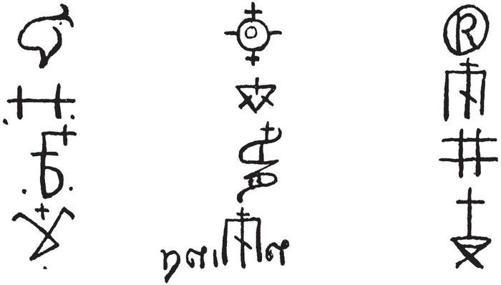

Symbols used by individual Venetian merchants to mark their goods

If there was one trade in hunger, there was another in luxury. The thirteenth century also witnessed a commercial revolution that promised the restless merchant cities of Italy a steadily rising tide of wealth. More coin was in circulation than ever before; people were moving from payments in kind to payments in cash; to investing rather than hoarding; to the legitimate loan of money; to international banking; to credit and bills of exchange; double-entry bookkeeping and new forms of entrepreneurial organisation. The invention of novel instruments of transaction facilitated the development of trade on an unprecedented scale. While twenty-five per cent of the urban population might be destitute,

there arose a desire to consume among the courts, churchmen and the rising middle class of urbanising Europe that found its expression in a demand for distant luxuries – and the means to pay for them. Venice traded not just in staples, but in conspicuous consumption. And this trade was largely orientated towards the incomparably richer, better provided East.