City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (9 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

This was theologically extremely tricky. The first stop on the crusade was to be the conquest of another Christian – and Catholic – city. Worse still, its new overlord, Emico of Hungary, had himself taken the cross. They would be attacking another crusader. It was true that Emico had shown no sign of actually going on crusade; as far as the Venetians were concerned he had cynically signed up purely for papal protection against such reprisals, but this still smacked of cardinal sin. Furthermore Innocent had been alerted by Emico to such a possibility and had already sent Dandolo an explicit warning ‘not to violate the land of this king in any way’. No matter. Dandolo promptly muzzled the papal legate, Peter Capuano, by preventing him from accompanying the fleet as the pope’s official spokesman, and continued to ready the ships. The slightly forlorn legate blessed the crusade whilst reserving his position on its objective and hurried back to Rome. Innocent prepared a threatening epistle. His early fears about the treacherous Venetians seemed to be fully confirmed. Within the assembling Christian army word probably leaked out that the first objective was to be a Christian city and Boniface of Montferrat, the titular leader of the crusade, politely excused himself from accompanying the expedition on its initial mission: he evidently wanted no part in Venice’s imperial projects, but the whole crusading expedition was caught between a rock and a hard place – it either went to Zara or it disintegrated.

*

Preparations were now hurried forward. In early October siege machines, weapons, food, barrels of wine and water were laboriously

carried, winched or rolled aboard the ships; the knights’ chargers were led snorting up the loading ramps of the horse transports and coaxed into the leather slings designed to let them swing with the lurch and roll of the sea; the doors were then caulked shut ‘as you would seal a barrel, because when the ship is on the high seas the whole door is underwater’. Thousands of foot soldiers, many of whom had never put to sea before, were crammed into the dark, claustrophobic holds of the troop carriers; the Venetian oarsmen took their places on the rowing benches of the war galleys; the blind Dandolo was led aboard the doge’s sumptuous vessel; anchors were raised, sails unfurled, ropes cast off. Venetian history would be strung together on the recital of its great maritime ventures, but few would surpass in splendour the departure of the Fourth Crusade. None would have a deeper effect on the Republic’s ascent to empire. It marked Venice out as a power whose maritime capabilities were unmatched in the Mediterranean basin.

For the landlubber knights, it was a spectacle that took the breath away and moved them to hyperbole: ‘Never did such a magnificent fleet sail from any port,’ was Villehardouin’s verdict. ‘One might say that the whole sea sparkled on fire with ships.’ To Robert of Clari, ‘it was the most magnificent spectacle to behold since the world began’. Hundreds of ships spread their sails across the lagoon; their banners and ensigns fluttered in the breeze. Standing out in the massed armada were some enormous castellated sailing vessels, rising like towers over the sea with their high poops and forecastles, each one badged with the glittering shields and streaming pennants of the crusader lords to whom they had been assigned, as symbols of magnificence and feudal power. The names of some of these survive: the

Paradise

and the

Pilgrim

, carrying the bishops of Soissons and Troyes, the

Violet

and the

Eagle

. The sheer height of these vessels was to play a significant part in the events ahead. Crusaders in their surcoats bearing the crosses of their nations – green for Flanders, red for France – crowded the stacked decks. The Venetian galley fleet

was led forward by the doge’s vessel, painted a significant vermilion, in which Dandolo sat beneath a vermilion canopy, ‘and he had four silver trumpets which trumpeted before him and cymbals making a tremendous sound’. Volleys of noise swept across the panoramic sea. ‘A hundred pairs of trumpets of both silver and brass which sounded the departure’ blared across the water, drums and tabors and other instruments thumped and boomed; the brilliantly coloured pennants streamed in the salt wind; the oars of the galleys dashed the waves; black-robed priests mounted the forecastles and led the whole fleet in the crusader hymn ‘

Veni Creator Spiritus

’. ‘And without exception, everyone, both great and small, wept with emotion and the immense joy that they felt.’ With this triumphant din and the pious release of pent-up feelings the crusading fleet swept out of the mouth of the lagoon, past the Church of St Nicholas and the outer spits of the Lido, for so many months a prison, and into the Adriatic.

Yet there were uneasy notes amongst the splendid noise. The

Violet

sank on departure. There were those with profound spiritual doubts about attacking Christian Zara; far away in Rome Pope Innocent was sitting, pen in hand, preparing to excommunicate any crusader who dared to do so. And the missing sum of thirty-four thousand marks would continue to haunt the expedition all the way round the coast of Greece, like an albatross dangling from the tall masts.

‘A Dog Returning to its Vomit’

OCTOBER 1202–JUNE 1203

The Venetians had every intention of using this magnificent fleet along the way to reassert their imperial authority in the upper Adriatic, to cuff insubordinate cities, threaten pirates and levy sailors. Where Venice saw this as a legitimate assertion of feudal rights, many of the crusaders, frustrated and impoverished by the long wait on the Lido, already perceived the whole venture as a perversion of crusading vows. ‘They forced Trieste and Mugla into submission,’ an anonymous chronicler bluntly asserted as the fleet worked its way down the coast, ‘they compelled all of Istria, Dalmatia, and Slavonia to pay tribute. They sailed into Zara, where their [crusading] oath came to naught. On the feast of Saint Martin they entered Zara’s harbour.’ Venetian ruthlessness was not always well received.

The fleet smashed through the harbour chain, forced its way in and proceeded to disembark thousands of men. The doors of the transports were prised open; the groggy, disorientated horses were led blindfolded onto dry land; catapults and siege towers were unloaded and assembled; a host of tents, with banners flying, was pitched outside the city walls. The Zarans surveyed this ominous enterprise from their battlements and decided to surrender. Two days after the fleet’s arrival they sent a delegation to the crimson pavilion of the doge to offer terms. The business of Zara was a purely Venetian matter, but Dandolo, either out of scrupulousness or a desire to make the Zarans sweat, declared that he could not possibly accept this until he had conferred with the French barons. He left the delegation kicking its heels.

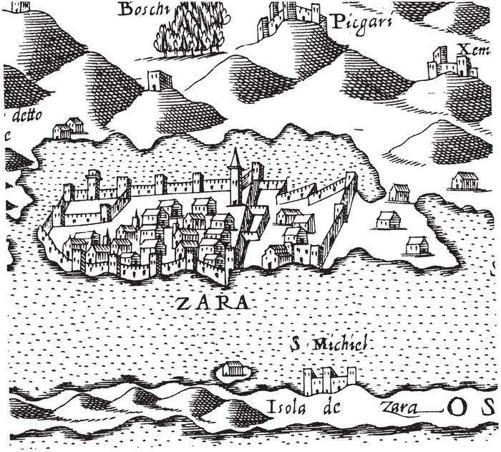

Zara and its harbour

Unfortunately for Dandolo – and as it turned out even more unfortunately for Zara – at almost the same moment a ship arrived from Italy carrying the furious interdict of Pope Innocent. The actual letter is lost but its contents were clearly restated later:

… we took care to strictly enjoin in our letter, which we believe came to your attention and that of the Venetians, that you not be tempted to invade or violate the lands of Christians … Those, indeed, who might presume to act otherwise should know that they are bound by the fetters of excommunication and denied the indulgence that the [pope] granted the crusaders.

This was extraordinarily serious. Excommunication threatened, at a stroke, to damn the very souls crusading was intended to save. The letter was a grenade thrown into the expedition’s uneasy pact and it opened up all the underlying tensions of the enterprise. A dissenting group of French knights, led by the powerful

Simon de Montfort, had always seen the diversion to Zara as a betrayal of crusader vows. While Dandolo was elsewhere discussing the surrender with a body of crusader lords, they called on the Zaran delegation waiting at the doge’s tent. They informed it that the French would refuse to attack the city, and ‘if you can defend yourself against the Venetians, then you will be safe’. Just to make sure the message got across, another knight shouted this information over the battlements. Armed with this promise the Zaran delegation turned on its heels and went back to the city, determined to resist.

Dandolo, meanwhile, had got the agreement of the majority of the leaders to accept the surrender and they all returned to his tent. Instead of the Zaran delegation, which had vanished, they were confronted by the abbot of Vaux, probably with Innocent’s letter in his hand, who stepped dramatically forward with all the force of papal authority and declared: ‘Lords, I forbid you, by the pope in Rome, to attack this city; for it is a place of Christians and you are pilgrims.’ A furious row broke out. Dandolo was incensed and rounded on the crusader leaders: ‘Sirs, by agreement I arranged the surrender of this city, and your men have taken it from me, although you gave me your word that you would help me to conquer it. Now I call on you to do so.’ Furthermore, according to Robert of Clari, he was not prepared to back down before the pope: ‘Lords, you should be aware that I won’t relinquish my vengeance on them at any price, not even for the pope!’

The crusader leaders, more squeamish, found themselves caught between excommunication and the breaking of a secular agreement. Shamefaced and appalled by de Montfort’s actions, they decided they had no option but to underwrite their commitment to the Venetian cause – the outstanding debt was tied up in the deal. Otherwise the crusade might just collapse. It was with heavy hearts that they agreed to this unpalatable act: ‘Sir, we will help you to take the city despite those who want to prevent it.’ The unfortunate Zarans, who had tried to surrender peacefully, now found themselves subjected to overwhelming force. They

tried to prick crusader consciences by hanging crosses from the walls. It made no difference. Giant catapults were wheeled up to bombard the walls; miners began to tunnel beneath them. It was all over in five days. The Zarans sued for peace on more humiliating terms. Barring a few strategic executions, the Venetians spared the citizens’ lives; the city was evacuated and the victors ‘looted the city without mercy’.

It was now mid-November and Dandolo pointed out to the assembled army that it was too late in the year to sail on; the winter could be passed pleasantly enough in the mild climate of the Dalmatian coast. It would be better to wait until spring. It was reasonable enough, unavoidable even, but this suggestion seems to have plunged the crusade into fresh crisis. The rank-and-file crusaders felt they were being yet again shamelessly exploited – and they largely blamed Venice. They had been imprisoned on the Lido, led astray to attack Christian cities, impoverished and deceived. The clock was ticking steadily on the year’s contract with Venice and they were no step nearer the Holy Land, let alone Egypt. The spoils of Zara had been largely appropriated by the lords. ‘The barons kept the city’s goods for themselves, giving nothing to the poor,’ wrote an anonymous eyewitness, evidently sympathetic to the plight of the common man. ‘The poor laboured mightily in poverty and hunger.’ Collectively they still owed thirty-four thousand marks.

Shortly after the sacking of Zara, popular resentment erupted into violence.

Three days later, a terrible catastrophe befell the army near the hour of vespers, because a wide-ranging and very violent fight broke out between the Venetians and the French. People came running to arms from all sides and the violence was so intense that in nearly every street there was fierce fighting with swords, lances, crossbows and spears, and many men were killed or wounded.

It was with considerable difficulty that the commanders regained control of the situation. The crusade was hanging by a thread.

What the ordinary crusaders did not know – and this would have horrified them far more – was that they had now been excommunicated for the attack on the city. In an exercise of creative crisis management, the crusading bishops simply bestowed a general absolution on the army and lifted the ban, which they had no authority to do. Over the winter of 1202–3 the rank and file whiled away the time on the Dalmatian coast in reasonable accord whilst waiting for the new sailing season, blissfully unaware that their immortal souls were still in grave peril. The Frankish barons decided to hurry an abjectly apologetic delegation back to Rome to try to sort the situation out. The Venetians refused point-blank to participate: Zara was their own business; on its capture was built the agreement which would lead to the return of the thirty-four thousand marks and as long as this debt remained outstanding, the whole Republic’s position was critical.