City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (6 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

This was not a good start. The threat of excommunication was heavy and Innocent did not trust Venice at all, but practically he had no choice but to bend a little: only the Republic could supply the ships.

So it was that when six French knights arrived at Venice in the first week of Lent 1201, the doge probably had a good idea of their mission. They came as envoys of the great crusading counts of France and the Low Countries – from Champagne and Brie, Flanders, Hainaut and Blois – with sealed charters that gave them full authority to make whatever agreements they saw fit for maritime transport. One of these men was Geoffroi de Villehardouin of Champagne, a veteran of the Third Crusade and a man with experience of assembling crusader armies. It was Villehardouin’s account that would form a principal, but highly partial, source for all that followed.

Venice had a long tradition of equating age with experience when it came to appointing doges, but the man the counts had come to see was remarkable by any measure. Enrico Dandolo was the scion of a prominent family of lawyers, merchants and churchmen. They had been intertwined in nearly all the great events of the past century and had built up an impressive record of service to the Republic. They had been involved in reforming the city’s church and state institutions in the middle years of the twelfth century and participated in Venice’s crusading ventures. By all accounts the male Dandolos were a clan of immense wisdom, energy – and longevity. In 1201 Enrico was over ninety. He was also completely blind.

No one knows what Enrico looked like; his physical image has been shaped by numerous anachronistic portrayals, so it is easy now to imagine a tall, thin, wiry man with a white beard and piercing but sightless eyes, steely in his resolve for the Venetian state,

sagacious with experience of many decades at the heart of Venice’s life during a century of rising prosperity – an impression for which there is no material substance. Of his personality, contemporary impressions and subsequent judgements have been sharply divided. They would match the divergent views of Venice itself. To his friends Dandolo would become the epitome of the Republic’s shrewdness and good government. To the French knight Robert of Clari he was a ‘most worthy man and wise’; to Abbot Martin of Pairis, a man who ‘compensated for physical blindness with a lively intellect’; the French baron Hugh of Saint-Pol called him ‘prudent in character, discreet and wise in making difficult decisions’. Villehardouin, who came to know him well, declared him to be ‘very wise, brave and vigorous’. To the Greek chronicler Niketas Choniates, who did not, he was destined to a counter-judgement which has also passed into the bloodstream of history: ‘a man most treacherous and hostile to the [Byzantines], both cunning and arrogant; he called himself the wisest of the wise and in his lust for glory surpassed everyone’. Around Dandolo would gather accretions of myth that would define less the man than the way that Venice would be seen both by itself and its enemies.

Dandolo had always been destined for high office, but some time in the mid-1170s he started to lose his sight. Documents that he signed in 1174 show a firm, legible signature well aligned along the page. Another in 1176 bears the tell-tale signs of visual impairment. The words of the Latin formula (‘I, Henry Dandolo, judge, have signed underneath in my hand’) slope away downhill to the right, as the writer’s grasp of spatial relationship falters across the page, each successive letter taking its stumbling position from an increasingly uncertain guess as to the orientation of its predecessor. It appears that Dandolo’s eyesight was slowly fading and in time utterly extinguished. Eventually, according to Venetian statute, Dandolo was no longer permitted to sign documents, only to have his mark attested by an approved witness.

The nature, the degree and the cause of Dandolo’s loss of sight were destined to become subjects of much speculation and to be

held as a key explanation for the events of the Fourth Crusade. It was rumoured that during the Byzantine hostage crisis of 1172, when Dandolo was in Constantinople, the emperor Manuel ‘ordered his eyes to be blinded with glass; and his eyes were uninjured, but he saw nothing’. This was held to be the reason why the doge harboured a profound grudge against the Byzantines. In another version he lost his sight in a street brawl in Constantinople. Variants of this tale perplexed the medieval world in all subsequent considerations of Dandolo’s career. Some held that his blindness was feigned, or not total, for his eyes were attested to be indeed still bright and clear, and how otherwise was Dandolo able to lead the Venetian people in peace and war? Conversely it was said that he was adept at covering up his blindness, and that this was a proof of the treacherous cunning of the man. It is certain, however, that Dandolo was not blinded in 1172 – his signature was still good two years later – nor did he himself ever apportion blame for it. The only explanation that he subsequently gave was that he had lost his sight through a blow to the head.

However it happened, it did nothing to dim the clarity of his judgement or his energy. In 1192 Dandolo was elected to the position of doge and swore the ducal oath of office to ‘work for the honour and profit of the Venetians in good faith and without fraud’. Despite the fact that Venice, always profoundly conservative in its mechanisms, was never given to a heady admiration of youth, the blind man who had to be led to the ducal throne remained an unusual choice; it is possible he was viewed as a stop-gap. Given his advanced years the electors could feel reasonably confident that his term of office would be short. None of them could have guessed that it had thirteen years to run, during which time he would transform the future of Venice – or that the arrival of the crusader knights would be the trigger.

Dandolo welcomed the knights warmly, examined their letters of credence carefully and, being satisfied with their authority, proceeded to the business. The matter was unfolded in a series of meetings. First to the doge and his council, ‘inside the doge’s

palace, which was very fine and beautiful’, according to Villehardouin. The barons were highly impressed with the splendour of the setting and the dignity of the blind doge, ‘a very wise and venerable man’. They had come, they said, because they ‘could be confident of finding a greater supply of ships at Venice than at any other port’ and they outlined their request for transport – the number of men and horses, the provisions, the length of time for which they requested them. Dandolo was evidently taken aback by the scale of the operation that the envoys outlined, though it is unclear exactly how detailed their projections were. It was a week’s work for the Venetians to size up the task. They came back and named their terms. With the thoroughness of experienced workmen quoting on a job they stipulated exactly what they would supply for the money:

We will build horse transports to carry 4,500 horses and nine thousand squires; and 4,500 knights and twenty thousand foot soldiers will be embarked on ships; and our terms will include provisions for both men and horses for nine months. This is the minimum we will provide, conditional on payment of four marks per horse and two per man. And all the terms we are setting out for you will be valid for a year from the day of departure from the port of Venice to serve God and Christendom, wherever that may take us. The sum of money specified above totals ninety-four thousand marks. And we will additionally supply fifty armed galleys, free of charge, for as long as our alliance lasts, with the condition that we receive half of all the conquests that we make either by way of territory or money, either by land or at sea. Now take counsel among yourselves as to whether you are willing and able to go ahead with this.

The per capita rate was not unreasonable. The Genoese had asked for similar from the French in 1190, but the aggregate sum of ninety-four thousand marks was staggering, equivalent to the annual income of France. From the Venetian point of view it was a huge commercial opportunity, shadowed by considerable risk. It would require the undivided attention of the whole Venetian economy for two years: a year of preparation – shipbuilding, logistical arrangements, manpower recruitment, food sourcing –

followed by a second year of active service by a sizeable section of the male population and the use of all its ships. It would commit the Venetians to the largest commercial contract in medieval history; it would mean the cessation of all other trading activity during the span of the contract; failure at any point would mean disaster for the city, because all its resources were involved. It was small wonder that Dandolo had studied the letters of authority so closely, drawn the contract so carefully and asked for half of the proceeds. The two dimensions were time and money; both had been scrupulously weighed. The Venetians were seasoned merchants; contracting was what they did and they believed in the sanctity of the deal. It was the gold standard by which Venetian life operated: its key parameters were quantity, price and delivery date. Such bargains were hammered out on the Rialto every day of the trading year, though never on this scale. The doge might have been surprised that the crusaders agreed so readily after only an overnight consideration. The envoys were particularly impressed by the Venetian offer to contribute fifty galleys at their own expense. It was not without significance. Nor was the seemingly innocuous phrase ‘wherever that may take us’ inserted in the contract without purpose.

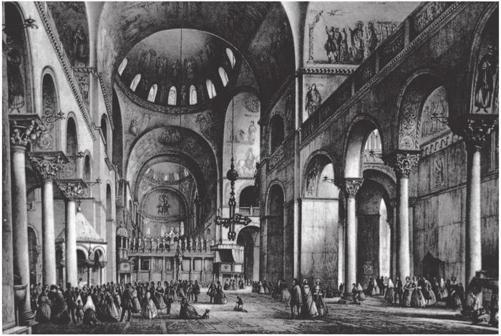

The interior of St Mark’s

The doge might have been driving the deal, but Venice defined itself as a commune, in which all the people theoretically had a say in the major decisions of the state. In this case their whole future was at stake. It was critical to obtain wide consent for the deal. Villehardouin recorded the process of Venetian democracy at work. The transaction had to be sold to an ever widening audience: first the Great Council of fifty, then to two hundred representatives of the Commune. Finally Dandolo called the general populace to St Mark’s. According to Villehardouin, ten thousand people were gathered together in expectation of dramatic news. In the smoky darkness of the great mother church, ‘the most beautiful church that might be’, wrote Villehardouin, who was evidently as susceptible as anyone to the atmosphere of the place, glimmering like a sea cave shot through with shafts of obscure

light and the smouldering gold of its mosaic saints, Dandolo constructed a scene of mounting drama, using ‘his intelligence and powers of reason – which were both very sound and sharp’. First he requested ‘a mass to the Holy Spirit and to beg God that he might guide them concerning the request the envoys had made to them’. Then the six envoys entered the great doors of the church and walked down the aisle. The Frenchmen, doubtless wearing their surcoats emblazoned with the scarlet cross, were the object of intense interest. People craned and jostled to catch a glimpse of the foreigners. Clearing his throat, Villehardouin made a powerful address to his audience:

My lords, the greatest and most powerful barons of all France have sent us to you. They have begged your mercy to take pity on Jerusalem, which is enslaved by the Turks, so that, for the love of God, you should be willing to help their expedition to avenge Jesus Christ’s dishonour. And for this, they have chosen you because there is no nation so powerful at sea as you, and they have ordered us to throw ourselves at your feet and not to get up until you have agreed to take pity on the Holy Land overseas.

The marshal flattered their maritime pride and their religious zeal, as if they had been personally called upon by God to perform this mighty deed. All six envoys fell weeping to the floor. It was an appeal direct to the emotional core of the medieval soul. A thunderous roar swept through the church, along the nave, mounting to the galleries and up into the swirling heights of the dome. People ‘called out with one voice and raised their hands up high and cried “We agree! We agree!”’ Dandolo was then helped to the pulpit, his sightless eyes sensing the moment, and sealed the pact: ‘My lords, behold the honour God has done you, because the finest nation on earth has scorned all others and asked

your

help and co-operation in undertaking a task of such great importance as the deliverance of Our Lord!’ It was irresistible.

The Treaty of Venice, as it came to be known, was signed and sealed the following day with all due ceremony. The doge ‘gave them his charters … weeping copiously, and swore in good faith on the relics of saints to loyally hold to the terms in the charters’. The envoys responded in kind, sent messengers to Pope Innocent and departed to prepare for crusade. Under the terms of the treaty, the crusading army would be gathered on the auspicious St John’s Day, 24 June the following year, 1202, and the fleet would be ready to receive them.

Despite the fervent assent of the population, the Venetians were, by nature, a cautious people, in whom the mercantile spirit had bred shrewd judgement, not given to flights of fancy, and Dandolo was a cautious leader. Yet any measured risk analysis of the Treaty of Venice would suggest that it involved hazarding the whole economy of the Commune on one high-stakes project. The number of men and ships required, the sums of money to be laid out – the figures were breathtaking. Dandolo was probably over ninety years old with presumably only a few years to live. He personally was responsible for pushing through this enormous project. On the face of it he had much to lose. Why on earth should he risk his declining years in this gamble?