City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (49 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

I promise you that from head to tail the whole fleet is conservatively more than six miles long. To tackle this armada at sea, in my opinion we would need not less than a hundred good galleys, and even then I don’t know how it would turn out; to be certain of winning, it’s necessary to have seventy light galleys, fifteen heavy galleys, ten sailing vessels each of a thousand

botte

[perhaps about six hundred tons] – all well armed … now we need to show our power … and send with all possible speed ships, men, food, money; if not, Negroponte is in peril, all our empire in the Levant will be lost as far as Istria.

Longo was predicting the collapse of the whole Stato da Mar. The Adriatic itself would be in terrible danger: Istria lay at the doorstep of Venice, just a night’s sail away.

In Venice, public prayers were being ordered. Late in the day, the danger was at last being perceived on the Italian mainland. Everyone now understood what defeat might bring. ‘The Turkish navy will soon be at Brindisi, then Naples, then Rome,’ wrote Cardinal Bessarion. ‘With the Venetians defeated, the Turks will rule the seas as they do the land.’ Pope Paul directed prayers be said throughout Italy. On 8 July a penitent procession of cardinals wound its way barefoot from the Vatican to St Peter’s; a Turk was baptised as a morale-raiser; everyone was exhorted to pray; indulgences were granted to people who fought or paid another to fight. Despite the vast fleet and Longo’s urgent words, the memory of Gallipoli buoyed Venetian confidence. Its naval supremacy had never been challenged in battle.

*

Negroponte – the Black Bridge – was the name the Venetians had given to both the principal town and the whole of the Greek island of Euboea. The island is a freak in the geological history of the Mediterranean. It lies so hard up against the eastern coast of Greece that it is hardly an island at all: a long ribbon of land, mimicking the rhythm of the mainland into which it interlocks, but separated from it by a drowned valley, the Euripus, which comprises a minor wonder of the marine world. The narrow channel acts like a hydraulic ram, pumping the water through in a series of tidal bores at the rate of fourteen a day, seven in each direction. At its narrowest point, where the island and the mainland are separated by a strait only fifty yards wide, the water surges with the speed of a mill race. It was here that the Venetians had their town, on the site of the ancient Greek settlement of Chalkis. This was the Italian state in miniature, impressively bastioned, with a harbour and a bridge linking it to the mainland that was surmounted, halfway, by a fortified tower and a double drawbridge to seal the island from intruders.

After the fall of Constantinople the strategic importance of the island was inestimable. Its population was never large – probably no more than three thousand – but it was Venice’s hub in the

northern Aegean. ‘The place was well stocked with wealthy men and great merchants … so that it was in its greatest splendour and prosperity,’ according to a flattering contemporary account.

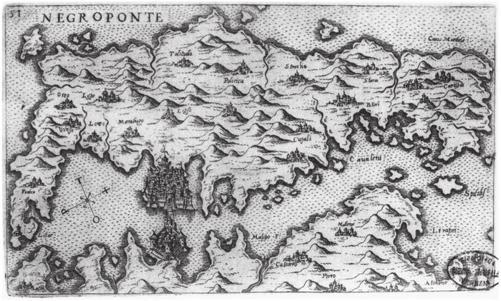

Negroponte, separated from mainland Greece by the Euripus. The Ottomans built their bridge to the right of the island’s black bridge. Da Canal’s fleet came down the strait from the north, to the left of the bridge.

Some time around 8 June, the Ottoman fleet reached Negroponte and anchored downstream from the city, disembarking men and guns on the shore. As intelligence had predicted months earlier, they immediately started constructing their own bridge of boats across the straits, south of the Black Bridge, whose drawbridge was now pulled up. What was obscured from the defenders was that this naval force was just one arm of a pincer movement. The shouts of defiance died on their lips on 15 June when a large army was spotted cresting the skyline on the mainland opposite, led by Mehmet himself. The personal presence of the sultan lent weight to a campaign; Mehmet only took to the field to win. Reining in his horse on the ridge, he spent two hours telescopically appraising the panorama below him: the narrow strait, the causeway with the fortress at its midpoint, then the moated and fortified city beyond, with the lion of St Mark carved on its outer

walls and fluttering from its towers; his own fleet rocking at anchor. The immaculately co-ordinated operation was a trademark of Mehmet’s style. His aim was to deliver a knockout blow before the Venetian fleet could respond.

His army of perhaps twenty thousand jingled down the slope to the banks of the Euripus, followed by a long train of camels and mules with all the impedimenta of a beseiging army. He crossed the pontoon bridge, erected his tents and started to draw his forces tightly around the city. The stock request to surrender was shouted over the walls: none of the inhabitants would be harmed; they would be free from all taxation for ten years; ‘To any nobleman who own a villa, he will give two. And the magnificent

bailo

and captain he will appoint as lords if they want to stay here; if not he will give them great honours in Constantinople.’ Mehmet was well aware that no Venetian governor could tamely surrender a city and return home alive.

The response was spirited. The

bailo

, Paolo Erizzo, conscious that da Canal’s fleet was on its way, declared that the place was Venetian and would remain so. He promised that within a fortnight he would burn the sultan’s fleet and root up his tents, then warming to his theme, invited the sultan ‘to go and eat pig’s flesh and come and meet us at the ditch’. When this insult was translated, Mehmet narrowed his eyes and resolved that no one would come out alive.

What followed was a miniature re-enactment of the siege of Constantinople, a pitiless spectacle of cruelty and blood. Mehmet had brought a battery of twenty-one large bombards that pounded the high medieval walls of the town without ceasing, day and night, terrifying the population and gradually reducing their bastions to rubble. The Venetian cannon had some success of their own, knocking out guns and killing their crews, but the weight of Ottoman firepower was relentless. Incendiary bombs and mortars, which lobbed missiles into the heart of the city, compelled the terrified population to shelter in the lee of the outer walls, ‘since the firing for the most part hit the centre of

the city’. ‘There was so much artillery and because the firing was so continuous,’ wrote Giovan-Maria Angiolello, a survivor of the siege, ‘it was impossible to make lasting repairs, since so many of our men were killed by the gunfire which scoured the city both frontally and from the flanks.’ The Turks inched their ladders and siege trenches forward into the rubble of the outer walls; on 29 June, accompanied by a wall of noise – the blaring of horns and the deep rhythmic thud of drums – Mehmet ordered a general assault. It was beaten back with much loss of life.

The

bailo

soon had to contend not only with continuous attacks but also the presence of a fifth column within his walls. Critical to the Venetian defence were five hundred mercenary infantry recruited largely from the Dalmatian coast under their commander Tommaso Schiavo. It was discovered that Schiavo had been sending envoys to the Ottoman camp; the administration covertly unpicked the plot, arresting and torturing his associates to expose a web of spying and intrigue that stretched years back and all the way to Venice. Mehmet had agents planted deep within the state. Under torture Schiavo’s brother revealed a plan to let the Turks into the city at the next attack. He was quietly killed.

The

bailo

now had to deal with Schiavo himself. It required extreme stealth as the traitor commanded a substantial force. Erizzo summoned him to the loggia – the administrative centre of the town – to discuss details of the defence. Doubtless suspicious, he came to the central square with a large and fully armed retinue. Entering the loggia, his fears were allayed by the

bailo

’s cordial manner. After some lengthy discussion, Schiavo dismissed his men back to their posts. With his back turned, twelve concealed men fell upon the commander and struck him down. He was strung up in the square by the foot.

Mehmet, meanwhile, was unaware of this turn of events. He was awaiting a pre-arranged signal to indicate that a certain bastion would surrender without a fight. The

bailo

prepared a trap. The signal flag was hoisted; when the Ottomans rushed forward, they were slaughtered, according to a chronicler, ‘like pigs’.

In the aftermath, the authorities in the town moved to kill many of the other ringleaders but the whole event had a deeply destabilising effect on the citizens’ morale. There was uproar in the streets and fighting between the townspeople and some Cretans on one side and the Dalmatian mercenaries on the other. An increasing number of the hired Slavs had to be put to death. With the supply of manpower ebbing away, public criers went round the streets ordering all boys of ten and over to the arsenal. Five hundred were chosen, rapidly trained in the use of handguns and sent to the walls, with the promise of a reward of two aspers for every Turk shot dead. ‘Each day in the evening,’ according to an eyewitness, ‘the

bailo

distributed to these boys three to five hundred aspers.’ A further major attack was beaten off.

The Ottomans continued to pound the walls, killing men on a daily basis, but Erizzo knew that if he could just hold out a little longer, da Canal would come. By the same token, Mehmet became increasingly anxious. To shore up his position, he had boats dragged over land and a second bridge constructed on the other side of the Black Bridge, as a defence against a rescue attempt down the channel from the north. He stepped up the bombardment, pulverising the walls and mounting attacks day and night to wear down the defence. He interspersed these with promises of safe conduct for a peaceful surrender. On the morning of 11 July, after three days of heavy gunfire, Mehmet was about to launch what he hoped might prove the final assault when he was stopped dead in his tracks.

Ottoman lookouts suddenly became aware of the Venetian fleet sweeping down the Euripus channel from its northern end. There were seventy-one ships, short of Longo’s recommended hundred, but still a sizeable force, including a powerful squadron of fifty-two war galleys and one weighty great galley, much feared by the Turks. They were under sail, making strong headway down the strait with the breeze and the tidal bore behind them. At a stroke Mehmet was horribly vulnerable. The fleet had only to smash the pontoon bridges to sever the Ottoman line of retreat

and isolate it on the island. Mehmet was said to have shed tears of impotent rage at the imminent ruin of his plan; he mounted his horse ready to escape from the island. On the walls of the citadel the defenders’ spirits rose. Relief seemed certain. Another hour and the bridges would be broken.

Then, quite inexplicably, the fleet stopped and anchored upstream. And waited.

Nicolo da Canal, captain-general of the sea, was a scholar and a lawyer rather than a seaman, more used to carefully weighing legal options than to decisive action. At that moment the lawyer’s instinct came into play. He was worried for the safety of his ships against gunfire and unnerved by the strange shifts of the current. He ordered the fleet to pause. His captains urged him forward; he resisted. Two Cretans begged to charge the first pontoon bridge in the great galley with the momentum of the wind and the tidal bore. Some of the sailors had family in the city; the will was there to do or die. Reluctantly permission was granted. The galley raised sail, but just as it was underway, da Canal changed his mind. It was commanded back by cannon shot.

On the walls, the defenders watched all this – first with joy at the prospect of rescue, then with disbelief, finally with horror. They sent increasingly desperate signals to the static fleet – torches were lit and extinguished, then the standard of St Mark was raised and lowered. Finally, according to Angiolello, ‘a great crucifix, the size of a man, was constructed and carried along the side of the city facing towards our fleet, so the commanders of the fleet might be moved to have some pity on us in ways that they could well imagine for themselves’. To no avail. Da Canal took his fleet back upstream and anchored. ‘Our spirits sank,’ remembered Angiolello; ‘and [we] were left with almost no hope of salvation.’ Others cursed: ‘May God forgive the individual who failed to perform his duty!’

Mehmet was quickest to react. Responding to this surprising turn of events, he immediately announced an all-out attack early next day and personally toured the camp on horseback promising

the troops everything in the city by way of plunder. He then commanded a large detachment of hand gunners to the upper bridge to protect it from da Canal’s fleet. In the dark hours before dawn, to the customary din of drums and trumpets, he ordered forward his least reliable troops – ‘the rabble’ – to wear down the defence. As they were shot down, the regulars advanced over the trampled corpses and stormed their way in. The whole population, men, women and children, participated in a last-ditch defence, barricading the narrow lanes and hurling scalding water, quicklime and boiling pitch on the enemy as it battled forward, foot by foot, street by street. By mid-morning they had reached the central square; from the fortress on the bridge, the defenders hoisted a black flag as a last despairing plea for help. Da Canal responded too little and too late. A half-hearted assault was mounted on the pontoon, but when the sailors saw the Ottoman flag fluttering from the walls, the captain-general raised his anchor and sailed off, leaving the despairing populace to a ghastly fate. Alvise Calbo, commander of the city, was killed in the Church of St Mark, Andrea Zane, the treasurer, in the Church of St Bastiano. Heaps of bodies were piled up in the streets. Mehmet remembered the jibes about pig meat and issued stern orders: no prisoners. Those who surrendered were slaughtered on the spot. Others were pointedly taken to the Church of the Holy Apostles to be killed. Their heads were piled up outside the patriarch’s house. In cold fury, Mehmet ordered any of his men hiding profitable captives to be beheaded along with their victims; he had the galleys searched accordingly.