City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (51 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

Pyramid of Fire

1498–1499

On 31 October 1498 Andrea Gritti wrote from Constantinople to Zacharia di Freschi in Venice: ‘I can’t tell you more about business and investments than I’ve told you already; if prices go down I will let you know.’ Gritti, forty-one years old, was well established in Constantinople as a Venetian grain trader. He was also a spy, sending back information to the senate

sub enigma

– in coded or concealed messages to a fictional business partner. The meaning in Venice was plainly taken: ‘The sultan continues to assemble a fleet.’

For nearly twenty years after Mehmet’s death, peace with the Ottomans had held firm. Bayezit II, who inherited the throne in 1481, initially promised more tranquil times for Christian Europe. Bayezit was known as ‘the Sufi’; he was devoutly religious, mystical even, with a keen interest in poetry and the contemplative life, and for a long time relations with his Christian neighbours remained temperate. He even released Venice from its annual tribute of ten thousand ducats. In the interim, the Republic felt itself more than compensated for the loss of Negroponte by the acquisition of Cyprus in 1489.

But there were other, strictly worldly reasons for Bayezit’s quiescence. Because of his father’s appetite for war he had inherited an empty treasury and an exhausted army – and he remained fearful of a counter-crusade in the name of his exiled brother, Cem, who was being conveniently retained in the courts of Europe as a useful hostage. Underlying these restraints, the new sultan was aware of unfinished business in the Aegean: as long as Venice

held footholds in Greece, the Ottoman frontier was incomplete. When Cem died in 1495, Bayezit, encouraged by Venice’s enemies in Florence and Milan, felt the time right to sweep the Republic from Greece. This could not be achieved without a powerful fleet.

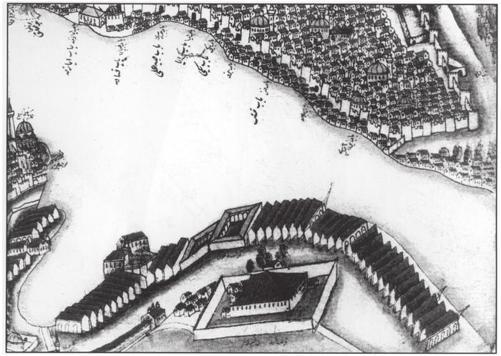

It was impossible to hide the preparations. To Andrea Gritti the evidence was literally in front of his eyes. After its fall, all Europeans were barred from living in Constantinople. Instead they resided on the hills of the old Genoese settlement of Galata, looking across the Golden Horn, the city’s deep-water harbour. Gritti could gaze down on the new arsenal below, which was not yet encircled by a high wall, and see the preparations: the arrival of men and materials, the sound of hammers and saws, the boiling of pitch and the endless trundling of ox carts.

The Ottoman arsenal in Constantinople

Gritti had been supplying a steady stream of subtle gossip back to the Venetian senate since 1494. As 1498 tipped into 1499, the messages were becoming more precise – he was providing guesstimates at timescales and objectives for a Turkish attack – and their despatch more risky. On 9 November 1498, he wrote, ‘The

corsair has taken a ship with a capacity of two hundred

botte

,’ meaning ‘The sultan is preparing two hundred ships’; on the 20th he declared himself uncertain of their purpose. On 16 February 1499 he wrote, in cipher, ‘It will depart in June … a great force by both land and sea, the number is not known, nor where it will go.’ This departure date was repeated on 28 March, in an encrypted mention that he was in prison for debt but hoped to depart in June. Sending letters by land was dangerous. Gritti’s method was to despatch messengers along the old Roman road to the port of Durazzo, then across to Corfu. Capture for these men meant certain death. In October 1498, the

bailo

in Corfu reported the fate of two messengers sent back to Gritti. The first was discovered buried under a dungheap in a village along the way; the second was taken once he reached the city. He was now despatching a third. In January, Gritti wrote back to say that he ‘will write no more by land because of the great danger’.

Both sides claimed peace while preparing for war. In Constantinople it was given out that a fleet was being readied against pirates. The Venetians were not deceived; it was too powerful simply for policing operations. ‘They are spending money furiously,’ Gritti had pointed out, ‘it’s being disbursed without even being requested – this is a sure sign.’ No one, however, could be certain of the objective. Theories, spying reports, indications poured into Venice from listening posts across the sea – a fuzzy but ominous crescendo of ill-omened noise. Deception was rife. When the latest ambassador arrived from Venice in April, it was reported by the diarist Girolamo Priuli that ‘the sultan honoured and banqueted him as an ambassador was never before treated there and that he has sworn peace and will never break the treaty with the Venetians … but the Venetians, having taken mature counsel on this, resolved to give no credence to such promises’. But was the operation being prepared against Venice? Rhodes was mooted and the Black Sea. There were even rumours of a strike against the Muslim Mamluk: letters were received from Damascus and Alexandria in May that a large number of Turkish horsemen had

been seen on the Syrian frontier. This sighting proved to be innocent – it was just an escort for the sultan’s mother on her way to Mecca. It was clear however that a sizeable army was also being assembled. There were fears for Zara; Corfu was guessed; people in Friuli braced themselves for raids.

*

The year 1499 was destined to be a cataclysmic one in the annals of Venetian history. It was tracked month by month in the diaries of two Venetian senators: the banker and merchant Girolamo Priuli, obsessive about the fiscal state of the Republic, and Marino Sanudo, whose forty-year record provides a vivid description of Venetian life; a third chronicler was the galley commander Domenico Malipiero, the only one to report from the front line.

They recorded an aggregation of malign events. The year started badly and went downhill. Venice was deeply entangled in the affairs of terra firma and money was tight. At the start of February the banks of the Garzoni family and the Rizo brothers failed. In May the bank of Lipomano went down; the next day when the bank of Alvise Pisani opened, ‘with a huge roar, a mighty crowd of people came running to the bank to get their money’. The Rialto was in turmoil. Priuli felt this to be extremely damaging:

… because it was understood throughout the world that Venice was haemorrhaging money and there was no money in the place, since the first bank to fail was the most famous of all and it had always had the greatest credibility, so that there would be a complete lack of confidence in the city.

In this climate, with rumours of the Turkish menace becoming louder, even the matter-of-fact Venetians were susceptible to superstition. An extraordinary aerial combat was observed in Puglia between vultures and crows; fourteen were picked up dead, ‘but more vultures than crows’, reported Malipiero. ‘God willing that this … is not an omen of some evil between Christians and Turks!’ More premonitions followed. With news of a Turkish

battle fleet growing by the day, a new captain-general of the sea was elected in March. At the ritual blessing of the battle standard in St Mark’s, Antonio Grimani held the admiral’s baton the wrong way up. Old men recalled other such instances and the disasters to which they had led.

Grimani was a money man, a fixer with political ambitions. He had made his fortune in the spice markets of Syria and Egypt. His astuteness was legendary. ‘Mud and dirt became gold to his touch,’ according to Priuli. It was said that on the Rialto men attempted to find out what he was trading in and followed suit, like aping a successful share dealer. Grimani had proved himself to be physically brave in battle but he was not an experienced naval commander and had no knowledge of manoeuvring large fleets. In the banking crisis of the early months of 1499 he got the job, which he undoubtedly saw as a stepping stone to the position of doge, by astutely offering to arm ten galleys at his own expense and advancing a loan of sixteen thousand ducats against the state salt trade. He set up the recruiting benches on the quay in front of the doge’s palace, the Molo, with a gaudy display of showmanship – ‘with the greatest pomp’, according to Priuli. Dressed in scarlet he invited the enlisting of crews before a mound of thirty thousand ducats heaped up in five glittering piles – a mountain of gold – as if to advertise his golden touch. Whatever the techniques, Grimani was highly successful in the organisation of the fleet. Despite shortages of men and money, outbreaks of plague and syphilis among the crews, by July he had assembled off Modon the largest maritime force Venice had ever seen. Grimani was talked up as ‘another Caesar and Alexander’.

There were however hairline cracks in these arrangements. The Republic had the right to commandeer the state merchant galleys for war service. In June all these galleys, already auctioned out to consortia for the

mude

to Alexandria and the Levant, were requisitioned and their

patroni

(tenderers) given the title and salary of galley captains. This was not popular; it was indicative of the fraying of group loyalty between the concerns of the state

and the commercial interests of sections of a self-serving noble oligarchy. Patriotism to the flag of St Mark was being put under strain. Severe punishments were proclaimed for non-compliance:

patroni

who did not assent would be banished from Venice for five years and fined five hundred ducats. There were still those who did not obey. Priuli believed, perhaps with hindsight, that Venice was being led towards disaster. ‘I doubt but that this glorious and worthy city, in which our nobility pervert justice, will through this sin suffer some detriment and loss and that it will be brought to the edge of a precipice.’ Over the summer, with all merchant activity suspended, the price of Levantine cargoes – ginger, cotton, pepper – started to rise. The demands of naval defence were starting to stress the city’s commercial system.

The news from Constantinople got bleaker. ‘With what great and frightening power does Turkish power resound across land and sea,’ wrote Priuli. In June all the Venetian merchants in the city were arrested and their goods confiscated. The customary penitential church services were held in the parishes of the lagoon. Meanwhile Gritti’s luck had run out. A messenger despatched by land with an unencoded message was intercepted and hanged; another was impaled on the way to Lepanto. Word got back to the city to arrest the merchant; he was soon in a gloomy dungeon on the Bosphorus under threat for his life.

It was reported that the Turkish fleet had passed out of the Dardanelles on 25 June, while a large army had set out for Greece at the same time. Doubtless some kind of pincer movement was intended. As the fleet worked its way round the Peloponnese, many of the impressed Greek crew ran away. Soon Grimani learned that the objective was either Corfu or the small strategic port of Lepanto at the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth. When the Ottoman army showed up outside the walls of Lepanto in early August both the objective and the tactics became clear. The walls of Lepanto were substantial and trundling cannon over the Greek mountains was not an option. The task of the Ottoman fleet was to deliver the guns, that of the Venetians to prevent

them. On the same day, the senate learned that Gritti was still alive.

The fleet that had sailed out of the Dardanelles in June had been prepared for battle at a moment of change in naval tactics. Sea warfare was traditionally a contest between oared galleys, but by the late fifteenth century experiments were underway in the use of ‘round ships’ – sail-powered, high-sided vessels known as carracks, traditionally merchant vessels – for military purposes. The Ottomans had constructed two massive vessels of this type. Like most innovations in their shipyards, these were probably adapted from Venetian models and were the work of a renegade master shipwright, one Gianni, ‘who having seen shipbuilding at Venice, had there learned the craft’. These ships, with their high stern and bow castles and steepling crow’s nests, were enormous by the standards of the day. According to the Ottoman chronicler Haji Khalifeh, ‘the length of each was seventy cubits and the breadth thirty cubits. The masts were several trees joined together … the maintop was capable of holding forty men in armour, who might thence discharge their arrows and muskets.’ These vessels were a hybrid species, snapshots in the evolution of shipping: as well as sails, they had twenty-four immense oars, each pulled by nine men. Because of their enormous size – the estimate is that they displaced 1,800 tons – they could be packed with a thousand fighting men and could, for the first time, carry substantial quantities of cannon able to fire broadsides through gunports. The Ottomans believed their two talismanic vessels would be invulnerable to Venetian galleys.