Civilization: The West and the Rest (59 page)

A third plausible scenario is that a rising middle class could, as so often in Western history, demand a bigger political say than they currently have. China was once a rural society. In 1990 three out of four Chinese lived in the countryside. Today 45 per cent of people are city-dwellers and by 2030 it could be as high as 70 per cent. Not only is a

middle class rapidly growing in urban China; the spread of mobile telephony and the internet means that they can form their own spontaneous horizontal networks as never before. The challenge this represents is personified not by the jailed dissident Liu Xiaobo, awarded the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, who belongs to an earlier generation of activists, but by the burly, bearded artist Ai Weiwei, who has used his public prominence to agitate on behalf of the victims of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. The counter-argument here comes from a young Beijing-based television producer I got to know while researching this book. ‘My generation feels like it’s the lucky one,’ she told me one night. ‘Our grandparents had the Great Leap Forward, our parents had the Cultural Revolution. But we get to study, to travel, to make money. So I guess we really don’t think that much about the Square thing.’ At first I didn’t know what she meant by that. And then I realized: she meant the

Tiananmen

Square ‘thing’ – the pro-democracy protest crushed by military force in 1989.

The fourth and final pitfall is that China may so antagonize its neighbours that they gravitate towards a balancing coalition led by an increasingly realist United States. There is certainly no shortage of resentment in the rest of Asia about the way China throws its weight about these days. Chinese plans to divert the water resources of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau have troubling implications for Bangladesh, India and Kazakhstan. In Hanoi patience is wearing thin with the Chinese habit of employing their own people in Vietnamese bauxite mines. And relations with Japan took such a turn for the worse in a dispute over the tiny Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands that China imposed an embargo on rare-earth exports, in retaliation for the arrest of a stray Chinese fisherman.

59

Yet these frictions are very far from sufficient grounds for what would be the biggest shift in US foreign policy since Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger reopened diplomatic communications with China in 1972. And the forty-fourth incumbent of the White House seems a long way removed from the realist tradition in American foreign policy, despite the impression left by his visits to India and Indonesia in late 2010.

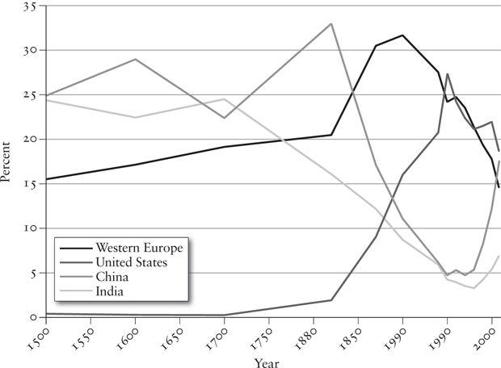

Europe, America, China and India, Estimated Shares of Global GDP, Selected Years, 1500–2008

The dilemma posed for the ‘going’ power by the ‘coming’ power is always agonizing. The cost of resisting Germany’s rise was heavy indeed for Britain; it was much easier quietly to slide into the role of

junior partner to the United States. Should America seek to contain China? Or appease China? Opinion polls suggest that ordinary Americans are no more certain how to respond than the President. In a recent survey by the Pew Research Center, 49 per cent of respondents said they did not expect China to ‘overtake the U.S. as the world’s main superpower’, but 46 per cent took the opposite view.

60

Coming to terms with a new global order was hard enough after the collapse of the Soviet Union, which went to the heads of many commentators. But the Cold War lasted little more than four decades and the Soviet Union never came close to overtaking the US economy. What we are living through now is the end of 500 years of Western predominance. This time the Eastern challenger is for real, both economically and geopolitically. It is too early for the Chinese to proclaim ‘We are the masters now.’ But they are clearly no longer the apprentices. Nevertheless, civilizational conflict in Huntington’s sense still seems a distant prospect. We are more likely to witness the kind of shift that in the past 500 years nearly always went in favour of the West. One

civilization grows weaker, another stronger. The critical question is not whether the two will clash, but whether the weaker will tip over from weakness to outright collapse.

Retreat from the mountains of the Hindu Kush or the plains of Mesopotamia has long been a harbinger of decline and fall. It is significant that the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan in the

annus mirabilis

of 1989 and ceased to exist in 1991. What happened then, like the events of the distant fifth century, is a reminder that civilizations do not in fact appear, rise, reign, decline and fall according to some recurrent and predictable life cycle. It is historians who retrospectively portray the process of dissolution as slow-acting, with multiple over-determining causes. Rather, civilizations behave like all complex adaptive systems. They function in apparent equilibrium for some unknowable period. And then, quite abruptly, they collapse. To return to the terminology of Thomas Cole, the painter of

The Course of Empire

, the shift from consummation to destruction and then to desolation is not cyclical. It is sudden. A more appropriate visual representation of the way complex systems collapse may be the old poster, once so popular in thousands of college dorm rooms, of a runaway steam train that has crashed through the wall of a Victorian railway terminus and hit the street below nose first. A defective brake or a sleeping driver can be all it takes to go over the edge of chaos.

Can anything be done to save Western civilization from such a calamity? First, we should not be too fatalistic. True, the things that once set the West apart from the Rest are no longer monopolized by us. The Chinese have got capitalism. The Iranians have got science. The Russians have got democracy. The Africans are (slowly) getting modern medicine. And the Turks have got the consumer society. But what this means is that Western modes of operation are not in decline but are flourishing nearly everywhere, with only a few remaining pockets of resistance. A growing number of Resterners are sleeping, showering, dressing, working, playing, eating, drinking and travelling like Westerners.

61

Moreover, as we have seen, Western civilization is more than just one thing; it is a package. It is about political pluralism (multiple states and multiple authorities) as well as capitalism; it is about the freedom of thought as well as the scientific method; it is

about the rule of law and property rights as well as democracy. Even today, the West still has more of these institutional advantages than the Rest. The Chinese do not have political competition. The Iranians do not have freedom of conscience. They get to vote in Russia, but the rule of law there is a sham. In none of these countries is there a free press. These differences may explain why, for example, all three countries lag behind Western countries in qualitative indices that measure ‘national innovative development’ and ‘national innovation capacity’.

62

Of course Western civilization is far from flawless. It has perpetrated its share of historical misdeeds, from the brutalities of imperialism to the banality of the consumer society. Its intense materialism has had all kinds of dubious consequences, not least the discontents Freud encouraged us to indulge in. And it has certainly lost that thrifty asceticism that Weber found so admirable in the Protestant ethic.

Yet this Western package still seems to offer human societies the best available set of economic, social and political institutions – the ones most likely to unleash the individual human creativity capable of solving the problems the twenty-first century world faces. Over the past half-millennium, no civilization has done a better job of finding and educating the geniuses that lurk in the far right-hand tail of the distribution of talent in any human society. The big question is whether or not we are still able to recognize the superiority of that package. What makes a civilization real to its inhabitants, in the end, is not just the splendid edifices at its centre, nor even the smooth functioning of the institutions they house. At its core, a civilization is the texts that are taught in its schools, learned by its students and recollected in times of tribulation. The civilization of China was once built on the teachings of Confucius. The civilization of Islam – of the cult of submission – is still built on the Koran. But what are the foundational texts of Western civilization, that can bolster our belief in the almost boundless power of the free individual human being?

*

And

how good are we at teaching them, given our educational theorists’ aversion to formal knowledge and rote-learning? Maybe the real threat is posed not by the rise of China, Islam or CO

2

emissions, but by our own loss of faith in the civilization we inherited from our ancestors.

Our civilization is more than just (as P. G. Wodehouse joked) the opposite of amateur theatricals (see the

epigraph

above). Churchill captured a crucial point when he defined the ‘central principle of [Western] Civilization’ as ‘the subordination of the ruling class to the settled customs of the people and to their will as expressed in the Constitution’:

Why [Churchill asked] should not nations link themselves together in a larger system and establish a rule of law for the benefit of all? That surely is the supreme hope by which we should be inspired …

But it is vain to imagine that the mere … declaration of right principles … will be of any value unless they are supported by those qualities of civic virtue and manly courage – aye, and by those instruments and agencies of force and science [–] which in the last resort must be the defence of right and reason.

Civilization will not last, freedom will not survive, peace will not be kept, unless a very large majority of mankind unite together to defend them and show themselves possessed of a constabulary power before which barbaric and atavistic forces will stand in awe.

63

In 1938 those barbaric and atavistic forces were abroad, above all in Germany. Yet, as we have seen, they were as much products of Western civilization as the values of freedom and lawful government that Churchill held dear. Today, as then, the biggest threat to Western civilization is posed not by other civilizations, but by our own pusillanimity – and by the historical ignorance that feeds it.

INTRODUCTION: RASSELAS’S QUESTION

1

. Clark,

Civilisation

.

2

. Braudel,

History of Civilizations

.

3

. See also Bagby,

Culture and History

; Mumford,

City in History

.

4

. On manners see Elias,

Civilizing Process

.

5

. See Coulborn,

Origins of Civilized Societies

and, more recently, Fernández-Armesto,

Civilizations

.

6

. Quigley,

Evolution of Civilizations

.

7

. Bozeman,

Politics and Culture

.

8

. Melko,

Nature of Civilizations

.

9

. Eisenstadt,

Comparative Civilizations

.

10

. McNeill,

Rise of the West

.

11

. Braudel,

History of Civilizations

, pp. 34f.

12

. See Fernández-Armesto,

Millennium

; Goody,

Capitalism and Modernity

and

Eurasian Miracle

; Wong,

China Transformed

.

13

. McNeill,

Rise of the West

. See also Darwin,

After Tamerlane

.

14

. Based on data in Maddison,

World Economy

. The historic figures for global output (gross domestic product) must be treated with even more caution than those for population because of the heroic assumptions Maddison had to make to construct his estimates, and also because he elected to calculate GDP in terms of purchasing-power parity to allow for the much lower prices of non-traded goods in relatively poor countries.