Clash of the Sky Galleons (19 page)

Critch! Critch! Critch!

He spun round, just in time to see a long scaly tail disappear down the aisle behind him. He peered down the narrow gap. And there, scurrying away, was a scrabster -one of the more destructive examples of Edgeland sky-vermin. Gelatinous beneath an opaque, bleached shell, the creature had a whiplash tail, three clawed mandibles and a dozen or so spindly legs. Ratbit raised the crossbow and fired. There was a thud as the bolt embedded itself in the floor - the scrabster froze, squeaked, then scampered away between the crates, unhurt.

‘Damn you to Open Sky, Ratbit cursed, turning sideways on to slip down the aisle.

Two hundred crates were stacked tightly together in the cargo-hold beneath the fore-deck, each one containing a thousand candles made from the finest hammelhorn-rendered tallow, the best that the League of Taper and Tallow Moulders could produce. They burned for hours, smelled sweet and produced no drips of wax. The shrykes loved them. Unfortunately, so too did scrabsters. In the worst infestations, entire cargoes could be consumed.

Suddenly, as Ratbit turned a corner, there was the creature just ahead of him, crouching down on its spindly legs, its beady black eyes glinting back at him from the shadows.

‘There

you are,’ Ratbit purred, before loosing a second bolt. But the scrabster darted off before the bolt had even landed. ‘Sky curse you!’ he shouted as he slipped another bolt into the chamber and primed it.

Scrabsters were just one of the verminous creatures that could infest a well-stocked sky ship. Hull-weevils, bow-worms, hullrot- and mire-clams all floated, hovered or sailed on the air currents in the hope of finding a free ride on a passing sky ship. Ratbirds usually picked most of them off and kept the hull and cabins clear, but in a well-stocked cargo-hold, you had to be on constant guard …

Ratbit caught the sight of movement out of the corner of his eye. Slowly, silently, he twisted round, raising lantern and crossbow as he did so. And there, not half a dozen strides in front of him, was the scrabster. This

time, however, it was not looking at

him,

but rather at a narrow crack in the side of a crate, as if trying to determine whether it was wide enough to squeeze through.

It was a large specimen, fat, clawed and oozing gelatinously out of its knobbly shell which, Ratbit thought, rather suggested that it had already started on the tallow candles. Its black eyes extended on the end of thin stalks and glinted in the lantern light as they peered into the hole in the crate. A moment later - having made up its mind - it raised one claw to the splintered wood and cut round its edges.

Ratbit pulled the trigger, firing the crossbow bolt. It sped through the air with a soft whistle and embedded itself in the right flank of the revolting creature. For a moment, nothing happened. Then, as if a lightning bolt had passed through its body, the scrabster twitched and jolted, green ooze pouring from the wound as it emitted a strangulated high-pitched squeal.

The next instant, it flipped over and its claws went limp.

‘That’ll learn you,’ Ratbit murmured. He crossed over to the dead creature, seized its tail and pulled it free of the crate. Then, holding it up, he

inspected it by the light of the lantern - and gave a low groan. An empty egg sac hung down from beneath the creature’s shell. From behind him there came tiny scuttling sounds in the shadows.

‘Young’uns,’ Ratbit growled, reloading his crossbow. ‘This means war …’

In the small cabin on the port-side of one of the central rudder-cogs, Maris pulled open the storm shutters and let the light in.

‘That’s better,’ she said brightly, turning to Duggin the gnokgoblin. ‘Now we can see what we’re doing.’

She opened the sumpwood trunk that hovered in front of her and searched its velvet-lined compartments. They were full of small bottles and stoppered phials that clinked musically as she rummaged.

Tweezel the spindlebug had taught Maris everything she knew about cures and remedies. Her father’s old butler had had a medicine for every occasion. Tinctures for rashes, potions for aches and pains, poultices and salves for cuts and burns, grazes and bruises. Many was the time that he had patiently and methodically cleaned and dressed a cut or scratch that she’d picked up at the Fountain House School in the floating city.

It seemed so far away now, Maris thought…

Duggin peeled the poultice-dressing from the nasty-looking bump above his left eye and smiled.

‘Galerider’s

a lot bigger than what I’m used to, Mistress Maris, but to be hit by a swinging jib-sail - an old ferry pilot like me -why, it makes me blush …’

‘You’ll get used to the

Galerider,’

said Maris, gently. ‘I have. Now, hold still…’

She took the dressing from the gnokgoblin, reached into the trunk and pulled out a small pot of salve. As she unscrewed the pot, a sweet herbal fragrance - at once fruity and peppery - filled the small cabin. Duggin licked his lips.

‘That smells good,’ he said.

Maris laughed. ‘Certainly better than the smell of frying woodonions coming from the galley’

‘What is it, though?’

‘Hyleberry,’ said Maris. ‘It’s excellent as a salve for burns and bruises - and Welma, my old nurse, used to make jam from it as well. Absolutely delicious …’

Her eyes took on a distant look once more. Long ago, when they’d first met in her

father’s palace, Quint had burned himself, and she’d tried to soothe the burn by smearing hyleberry jam on his fingers. Her nurse, Welma, had been furious - not that she’d wasted the jam, but that Quint had been fiddling with the lufwood stove in the first place. But he was being brave, trying to protect her, just as he always did …

‘What are you thinking about?’ said Duggin, dragging Maris back from her memories.

‘I … I was just wondering how you got to be a sky ferry pilot,’ she lied, her cheeks reddening. She busied herself with the hyleberry salve.

‘I joined the leagues as a young’un,’ said Duggin. ‘But being a leaguer and taking orders from high-hats wasn’t for me. So then I got work on a rubble-barge in the boom-docks. Stayed there for ten years, and earned enough to get a sky ferry of my own built.’ He smiled at Maris. ‘Ten long years, they were. But the

Edgehopper

was worth every day of it.’

Maris smiled back and, leaning across, removed a roll of bandage from one of the chest’s velvet-lined compartments. She placed the end of the bandage gently over the gnokgoblin’s bruise. Next, taking care not to make it too tight, she wound it round his forehead and tied it behind his rubbery ear.

‘And now you’re a sky pirate,’ she said. ‘Just like the rest of us.’

A flock of snowbirds flew high over the stern of the

Galerider,

their plaintive mewing cries filling the sky.

‘Never thought I’d live to sail in a sky pirate ship,’ said

Duggin, joining Maris at the small cabin window, ‘and see snowbirds flying high over the Deepwoods.’

Maris adjusted the gnokgoblin’s bandage which had slipped down over one eye.

‘If you want to live any longer,’ she laughed, ‘next time you see a jib-sail, duck!’

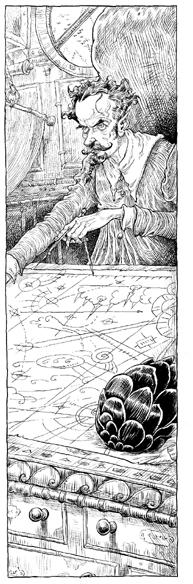

In the ornately decorated main cabin, high in the aft-castle of the

Galerider,

Wind Jackal stood before the great ‘Captain’s Desk’. With its edges and corners covered in inlaid calibrations of tilder ivory, and its leather surface tooled with flight paths and tether-points, the desk was a template on which to place the sky charts of tracing-parchment.

Wind Jackal flattened out a roll of parchment on the desk before him and weighted it down at the corners with four polished ironwood pinecones. Then he opened one of the broad, flat drawers of the desk and surveyed the array of glistening gold dividers laid out carefully upon its velvet lining. Each divider was set to the particular distance a sky ship could sail from ‘tether to tether’.

Depending on cloud and weather conditions, a sky ship could sometimes sail for days over the Edgelands before needing to descend and tether itself to the anchor rings, rocky crags or ancient ironwood pines that dotted the time-worn flight paths which led to the great markets of the Deepwoods. At other times, a sky ship would go barely a hundred strides at a time in the teeth of ice gales or driving storms - a course charted by the smallest dividers in the drawer.

Of course, a sky ship could always soar off high into the sky, far higher than its tether chain - yet only the most desperate or foolhardy captain would risk his vessel in Open Sky No, it made sense to judge your flight carefully from tether-point to tether-point, keeping low over the endless canopy of Deepwoods forest, and inching closer each day to the remote hammelhorn runs, timber yards or …

‘Great Shryke Slave Market,’ Wind Jackal murmured, picking up a large divider and walking it, point to point, across the expanse of parchment spread out before him on the Captain’s Desk. Twenty teth-erings at least, he thought, and that was only if the weather held …

He glanced across the cabin at the barometer on the wall and shook his head.

The needle was still falling. There was definitely a storm imminent - and it looked like a bad one. The last thing he wanted now was to get blown off-course. After all, it was hard enough plotting a path to the great market at the best of times - one could sail for weeks tracking the routes the slavers had taken.

That was the thing with shrykes. Always on the move. They would arrive at a particular part of the forest, set up their roosts - killing the trees and enslaving all who lived in the surrounding area - then, when the forest around had been stripped bare, they would up sticks, pack everything onto the backs of their prowlgrins and move on. In good weather, a voyage to the slave market could take weeks. In bad weather, with an ill wind and worse luck, a voyage could take years …

Wind Jackal laid down the divider and sat back in his tooled tilder-leather chair. Hands folded behind his head, he looked up at the ornately panelled ceiling and sighed a long, weary sigh. All his life he’d thrilled to the excitement of skysailing. He’d relished the challenge of plotting a course, calculating when to risk everything and when to sail safe and treetop close … But somehow, on this voyage, the joy had gone out of it. The charts, the dividers, the barometer were no longer his friends. Ahead seemed to lie only storm clouds and foreboding and …

‘Turbot Smeal,’ he murmured coldly.

Wind Jackal had barely slept for days. Every time he closed his eyes, the quartermaster’s evil face would loom up before him. Even here in his cabin with its

panelled walls and polished instruments, with the great Captain’s Desk inlaid with tilder ivory and clam-pearl, with its sumpwood hammock and fire-crystal lanterns -the place he felt most at home in the whole world - the spectre of Turbot Smeal hovered. He heard his nasal voice in the whispering of the sails, his laughter in the creaking of the hull, and sometimes when he looked in the mirror it was Smeal’s sneering face he saw, overlaid upon his own.

He leaned forwards and clasped his head in his hands. His stomach churned and his heart was thumping.

Just then, outside the broad windows, a flock of snowbirds flew past, their haunting cries filtering through into the cabin. Wind Jackal groaned and put his hands over his ears. It wasn’t the cry of the snowbirds he could hear, but Turbot Smeal’s mocking laughter …