Classic Christmas Stories (5 page)

Read Classic Christmas Stories Online

Authors: Frank Galgay

by Jim Rockwood

H

AS THE NEWFOUNDLAND OUTPORT Christmas really changed

that much from those of yesteryear?

Undoubtedly there havebeenchanges—the result of anumber of factors, not the

least of which are the vast improvements in transportation and communication

methods—which have resulted in a decrease in the number of small communities and

an opening up of those that remain.

Today, with roads, television, radio, telephone and telegraph facilities

inhabitants are not isolated to the same degree as in the past.

Accordingly, there has been a change in the celebration of Christmas, although

a typical old-fashioned Christmas can still be found and it does not require a

trip to some remote location.

It can be found in many small communities which exist near larger towns.

Here, residents still seem to be closer knit than those in the larger centres

and as a result it shows in their celebrations which sees Christmas the biggest

and longest.

However, even the length of the Christmas celebration is changed.

True, Christmas extends from Christmas Eve, until Old Christmas Day, but

commercialism has resulted in its beginning long before.

Commercialism, which some feel is destroying Christmas, has

seen Christmas start in late November when stores put up their Christmas

decorations, inaugurate their Christmas shopping hours and begin spreading their

Christmas shopping propaganda via all mediums.

By beginning interest in Christmas in late November some feel the interest in

“the big day” itself is diminished.

Christmas in the outports usually started Christmas Eve, although preparations

for the celebration got under way a day or so before.

The women of the house started preparations by cleaning house and baking the

many treats needed for the 12-day event that lay ahead not to be left out, the

men made their own preparations, not the least of which was filling the liquor

cabinet with either “store bought” or that well known other method known as

“moonshine, ” slightly illegal mind you, but certainly didn’t detract from the

taste.

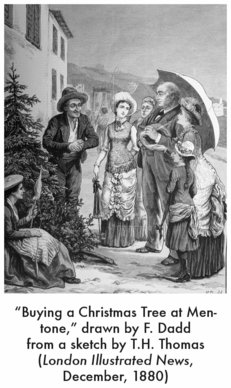

Christmas Eve itself was a time for putting all in order for the big day. It

meant an excursion to the woods by the men folk and children to select that

“just right” tree for the living room. Then it was off home to decorate

it.

Evening saw the children off early to bed awaiting the arrival of Santa Claus,

while the older folks went off to midnight service and then home to bed.

Bed, however, offered little sleep for the young. At or before the crack of

dawn it was downstairs—no one minded the cold floor because the stove wasn’t lit

yet—and into the presents.

Christmas morning saw the family off to church as a unit, normally without

mother who stayed home to cook Christmas dinner. Whether it be wild duck or

goose, whatever meat was available or if possible that

wonderful turkey, Christmas dinner was a treat fit for a king.

The table would be laden down with vegetables—mostly grown in the back

garden—along with breads, buns, cakes and of course the traditional boiled

Christmas pudding.

The majority of Newfoundlanders in the smaller outports were fishermen or

farmers and accordingly couldn’t afford a holiday during the five months of the

year when they had to make a living. So, when Christmas came it “certainly made

up for the summer vacation that a farmer or fisherman could not have, ” said one

person who lived for a number of years on the south coast.

The 12-day period was one of continuous parties, teas, socials, dances, times

and of course the “mummering” without which a Newfoundland Christmas would not

be complete.

Starting on Christmas Eve, children and adults would disguise themselves in old

clothes, cover their faces and visit other members of the community. When they

would arrive at the door, they’d ask “any mummers tonight, ” and when invited in

would sing and dance before unmasking and receiving a piece of Christmas cake

and a “drop of good cheer.”

Unfortunately, mummering is something that just about disappeared.

A noted Newfoundlander a few years ago, in an address to a local service club,

said that mummering is not something which originated here, but is “as old as

man himself.”

Lodges and societies were an integral part of Newfoundland outports and during

the Christmas season each in turn had its “time.”

These were for the entire community. Children played and frolicked while the

adults danced to music supplied by accordions and fiddles. Food was in

abundance. Hard beverages were not provided at the “time, ” but many the man and

younger person who sneaked outside for a “nip.”

In addition to the community-wide activities, Christmas was a time for visiting

friends and neighbours. Whenever one visited a neighbour’s home they were

required to taste the Christmas cake and sip a drop of rum or wine while the

children got the traditional syrup.

Times are changing, the traditional outport Christmas with it. However, while

adults may find changes, for children Christmas remains

a

mystical and wonderful experience.

Could it be that the child’s ability to believe in fantasy makes the

difference?

Christmas, noted Reginald Sparkes, a former speaker of the House of Assembly,

some years ago, is “a microcosm of our culture” and reflects every shade of

us.

Western civilization has achieved a goal of affluence during the recent

decades, but “nothing can be had without a price.” We gained a whole world, but

have lost the ability to enjoy pure fantasy.

Maybe the only way to get back many of the fast-fading customs of Christmas

past is to become like little children for one day, and in so doing recapture

the feeling of good will and only then will Christmas be not a “feast of

remembrance, but a feast of beginning.”

Christmas can be what every individual makes it.

by P. K. Devine

N

EARLY EVERY CIVILIZED COUNTRY intheworld has its

customs and superstitions peculiar to Christmas, and to this rule Newfoundland

is no exception. Our forefathers brought their traditions with them from

England, Ireland and Scotland, and they are, though gradually dwindling away,

still handed down to their descendants, to this day, especially among the people

of the outports.

On the “French Shore, ” at midnight on Christmas Eve, a live brand from the

Yule-log is solemnly taken out doors and thrown over the house, to preserve it

from being burnt down the coming year.

Peculiar observance is attached to the crowing of the cock on Christmas night,

and it is a common thing in Bonavista Bay to hear the people say, when the cock

crows in the stillness of Christmas Eve night, “He is scaring away the evil

spirits from the Christmas Holy Day.”

Most people believe, too, that the cattle kneel at the Manger when the cock

strikes twelve.

On Christmas Eve, at Broad Cove (Bonavista Bay), a custom brought from Ireland

by the generation of hardy pioneers, long passed away, is still religiously

observed, and is believed to ensure plenty of provisions and good times during

the coming year. A loaf of the Christmas baking is cut into four parts by the

housewife, and a quarter thrown to each such side of the house, indicating

plenty from north, south, east and west.

It is also believed that the deer kneel on Christmas night,

and it is a common thing for those who go in the bottoms of the Bays “on winter

works” to stay up all night to watch the caribou kneeling on the snow.

This custom is also peculiar to the woodmen of Upper Canada, where the

lumbermen and hunters also believe that horses and cattle have, on Christmas

night, the gift of speech, but that to play eavesdropper on them means death

before the New Year.

This belief is also common in Switzerland. According to an Alpine legend, a

doubting servant once hid in his master’s barn yard on a Christmas Eve, to prove

to his neighbours that they were fools to believe such trash. Upon the striking

of twelve, he heard a farm horse say, “We shall have hard work to do this day

week.” “Yes, ” replied his mate, “the farmer’s servant is heavy and the way to

the graveyard is long and steep.” Upon New Year’s Day, the servant was

buried.

In French Canada, Christmas is still marked among the farmers by many of the

old customs brought from Brittany by the early settlers. The children are told

that the domestic animals have the gift of speech on Christmas Eve, as a memento

of their presence in the stable when our Blessed Saviour was born. The little

children are taken to the Midnight Mass to see the Manger with the Infant Christ

lying therein, and the ox and the ass in the immediate foreground.

Under the French regime the Midnight Mass was always saluted by the firing of

the guns at the fortress, at Quebec, five times in succession.

In Russia, the home of “Santa Claus, ” it is easy to believe that special

observances are attached to the celebration of Christmas Eve. At sunset the

peasantry go in procession to the houses of the local dignitaries and serenade

them, when money is lavishly distributed among them. At sunset a sacred feast is

held, after which the nobleman, or “little father, ” as he is called invites the

peasants to behold a gigantic pine tree prepared in their honor and decked with

gifts which he distributes among those present. Herein can be recognized the

counterpart of our Santa Claus.

In Norway and Sweden, every member of the household must bathe on the day

before Christmas. In the evening, the Bible history of the Nativity is read in

every home, followed by special prayers. In the villages, among the peasants, a

candle is placed in every window to guide Kristine (Santa Claus) on his way. A

pan of meal and sheaf of wheat upon a pole are placed at each

door as an offering to the friends of Heaven, the little winter birds.

Games and dances are held in many of the houses on Christmas night, the parties,

like in our own Newfoundland, being often interrupted by masquerades, who sing

and dance a pantomime, and are at the conclusion rewarded with cakes, sweetmeats

or money. The small boy also have customs peculiar to themselves, and clad in

white pass from house to house, one of them carrying a star shaped lantern,

representing the Star of Bethlehem, and another a box containing two images to

represent the Virgin and Child.

It will be seen that there is certain resemblance in all the Christmas customs

of northern Europe to our own, which is very interesting to trace, and shows

that they all had a common origin.

Telling fortunes, by melting lead, on Christmas and New Year nights, is a

custom still kept up among the ladies in at least one village I know of in

Newfoundland. It is invariably done to obtain some knowledge of what kind of a

looking fellow the future husband will be, and whether the result will confirm

the omen of the cards and about the “dark-haired man across the water, ” or

not.

In Poland when the marriageable maiden yearns to get an idea of the appearance

of her future husband, she draws a stick at haphazard from a heap of wood on

Christmas Eve. As the stick proves to be long or short, straight or crooked, so

shall the husband to be. She next proceeds to find out his occupation, by

dropping hot lead into cold water. The lead will form an imaginary plane

(carpenter), or a last (shoemaker), pair of scissors (tailor), and so on, to all

the trades. This practice is still kept up on New Year’s night among the

peasantry of England and Ireland.

Who will not say that those practices are so conducive to the object aimed at

as the palmistry and Christian science of the so-called cultured and enlightened

people of the present day.

The utilitarian spirit of the age deals with those old customs and traditions

with a ruthless hand. Many of the old customs that our forefathers of

Newfoundland observed at Christmas, in the days of the open-fireplace, are

looked on by their descendants with ridicule, if not with contempt.

Cui

bono?

After a hard season’s work at the fishery, the harmless sports and

relaxation of the Christmas season made new men of them, and a firm religious

belief quickened them into close touch with the grand story of the Nativity and

made them better Christians. Phlegmatic and silent

fishermen,

who had not a word to say all the year round, now blossomed into Grand Knights

of St. Patrick, St. Michael and St. George, Hector Alexander, etc., and gave out

their heroic speeches in verse as they went in fantastic mumming costume from

one neighbours’ house to another. At the village of Vocksinge, the last of them

passed away to his eternal reward a year ago. Alas! Old age and hard work had

shrivelled him up to unheroic proportions. But “poor old Tommy Holland” once

stood on the floor on Christmas night, a veritable hero, as he recited:

“Here come I, Hector, the renowned Hector,

King Priam’s only son, ” etc.

May the light of Heaven shine upon them all, this Christmas morn.