Climbing Up to Glory (11 page)

Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

From the outset of the Civil War, slaves expended a great deal of effort to learn as much about the war as possible. Children, in particular, became adept at gleaning information from conversations they overheard among both black and white adults. For example, one former slave, who was a small child when the war erupted, recalled: “We colored chaps knew when the war commenced, though we didn't clearly understand what it was all about, but occasionally we got a hint from the older slaves, who had better opportunities for getting news, that somehow, we were the cause of the misunderstandingâthe âunpleasantness' as somebody called it.” As a consequence, slaves “understood in a vague way, that our friends at the North were doing battle for us, or, at least, were on our sideâand all our sympathies were with them.”

168

Likewise, Lizzie Davis, a former slave from South Carolina, became aware of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter because “my parents en de olden people speak bout dat right dere fore we chillun.”

169

A former slave in Tennessee recalled how during the war she and the other children “would go round to the windows and listen to what the white folks would say when they was reading their papers and talking after supper.”

170

Most slaves, including children, learned about the war and its progress through the “grapevine telegraph.” Young Booker T. Washington would sit up late at night with his mother and the other slaves and listen attentively to the whispered discussions about the progress of the fighting. He maintained that “every success of the Federal armies and every defeat of the Confederate forces was watched with the keenest and most intense interest.”

171

Despite the often successful efforts of slave children to solicit news, Southern whites still tried to prevent them from learning about the war. But as the conflict progressed, it became virtually impossible to keep it from the children. How could this information be concealed when they could observe Southern whites enlisting, drilling, and marching off to war? Rachel Harris, a young slave in Mississippi, recollected, “I went with the white chillun and watched the soldiers marchin'. The drums was playin' and the next thing I heerd, the war was gwine on. You could hear the guns just as plain. The soldiers went by just in droves from soon of a mornin' till sundown.”

172

The situation was so serious that even some of the very youngest were aware of what was going on. Ann Nettles, for example, a four-year-old in Georgia at the outset, explained, “Dey was sad times, honey; all de people was goin' to war wid de drums beatin' all aroun' and de fifes blowin'.”

173

The reality of death also brought the war home for many slave children. For instance, Mary Williams, a ten-year-old at the time who lived on a plantation in Georgia, vividly recalled the death of one of her young masters. Her mistress received a letter one day informing her how her son had been “in a pit with the soldiers and they begged him not to stick his head up but he did anyway and they shot it off.” In Mary's words, “Old mistress just cry so.”

174

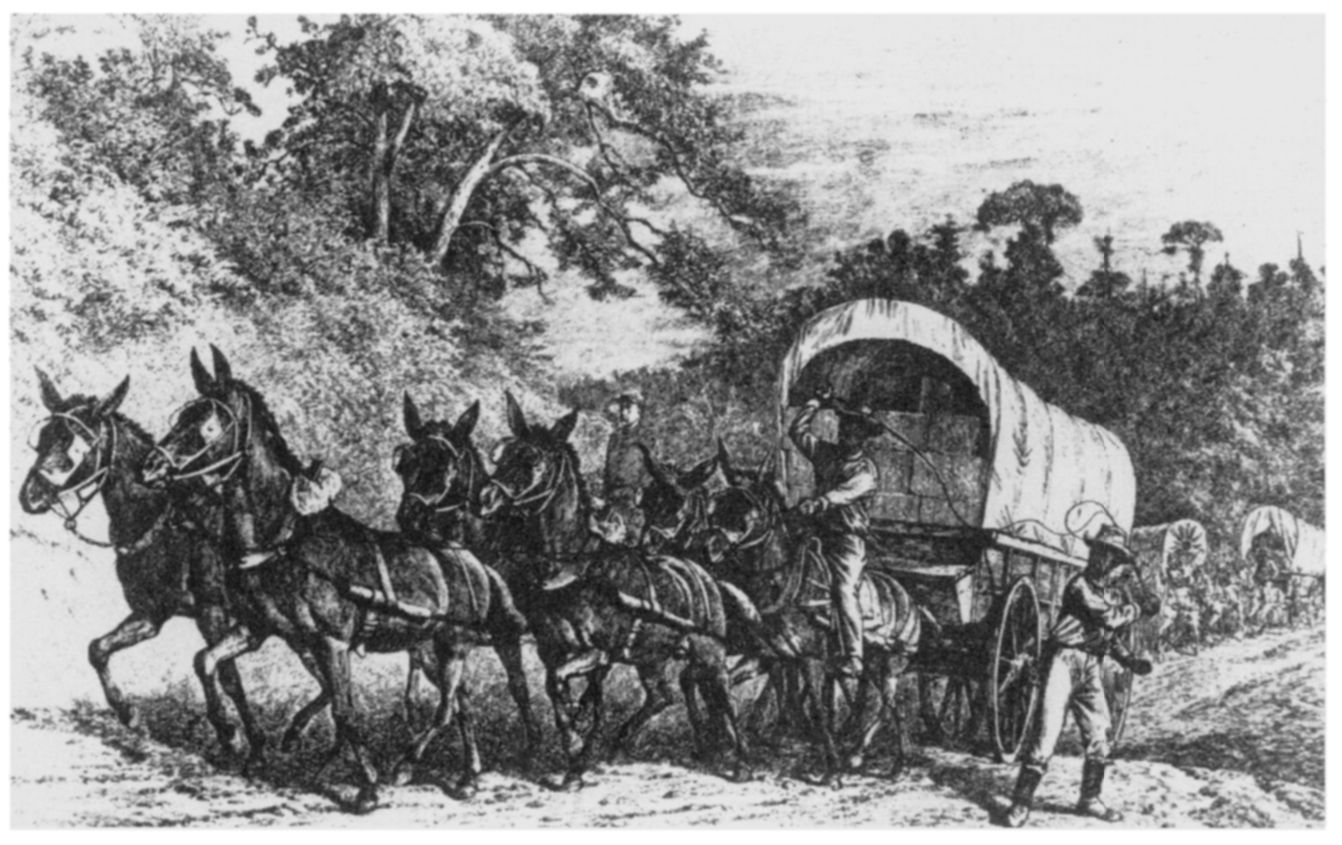

NEGROES PLAYED AN IMPORTANT ROLE IN OBTAINING SUPPLIES FOR GENERAL GRANT.

Courtesy of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History

As expected, when many white men went off to fight for the Confederacy and slave men abandoned the plantations in large numbers to enlist in the Union army, slave children's workload had to be expanded. James Henry Nelson, a ten-year-old when the war concluded, declared, “You know chillun them days, they made em do a man's work.”

175

James Gill longed to return to the antebellum summers when as a slave child in Arkansas, he spent most of his time fishing and swimming. Now, he had to work around the clock.

176

Moreover, Eliza Scantling, fifteen years old in 1865, recalled how she “plowed a mule an' a wild un at dat. Sometimes me hands get so cold I jes cry.”

177

Slaves and free blacks also assisted the Confederacy. The Confederate and state governments obtained slave laborers by impressment, a means of legal seizure at a fixed price, and by contract with their masters for their use for a limited time. Because of the acute labor shortage in the South, by the fall of 1862 most states had authorized the impressment of slaves. In the following year a desperate Confederate government passed a law, which it put into practice in 1864, calling for the impressment of 2,000 slaves. President Davis encouraged the impressment of slaves throughout the war, but the results were not gratifying. Owners did not like the principle of impressment, even though they were compensated, and most slaves disliked it because the work they were doing for military authorities was more strenuous than the work they were accustomed to doing for their masters. Nonetheless, Confederate and state governments were able to secure the services of thousands of slaves who carried out important tasks. In the Confederate army, slaves served as cooks, teamsters, mechanics, hospital attendants, ambulance drivers, and common laborers. Much of the labor in the construction of fortifications was done by slaves, and gangs of slaves and free blacks repaired the railroads and bridges wrecked by invading Union armies. They worked in factories that manufactured gunpowder and arms. Blacks constituted 310 of the 400 workers at the naval arsenal in Selma, Alabama, in 1865.

178

In addition, many affluent Confederates brought their black body servants to war with them. These men cut hair, ran errands, secured rations, cleaned the quarters, washed clothes and groomed uniforms, and polished swords, buckles, and spurs. They also took care of the wounded, served as mule and horse tenders, mail carriers, water carriers, and even entertainers; they dug trenches and erected breastworks. For example, William Johnson, the servant of Major Cooke, could affix his signature to the articles of surrender. Of his war experiences in an interview in January 1938, only days before his death, Johnson recalled, “They kept me busy there. Whenever there was fighting, all of us Negroes had the camp to look after and when the shooting was over we had to help bring in the wounded.” He continued, “In between battles we had to keep all our masters boots polished, the horses and harness cleaned, and the rifles and swords spic and span. Sometimes, too we were all put to digging trenches or throwing up breastworks.”

179

Susanna Metts was one of a few slave women who accompanied their masters to war as cooks, laundresses, or nurses. In Susanna's case, she served Captain M. A. Metts, and his regiment, as a practical nurse.

180

A slave, Howard Divinity, was so outstanding as a forager that he became known throughout the rebel army as the “chicken provider of the Confederacy.”

181

At the tender age of eleven, Juda Dantzler acted as a mail carrier for the rebels,

182

and Wash Ingram served as water carrier for the Confederate soldiers in the battle of Mansfield, Louisiana.

183

Unlike those slaves who were impressed and therefore forced to assist the Confederacy against their will, a large number of the body servants regarded it as a badge of honor to be selected by their masters. For instance, of his master's decision to have him accompany him, Elodga Bradford remembered, “I never will foâgit de day he lef' fo' de war. I was de proudest nigger on de plantation. Doctor Charles was takin' me to de war wid him.”

184

Army Jack, a former slave, loved to recount his war experiences and to dwell on the period he served his master during the war. Indeed, he seemed to think that it gave him a certain prestige.

185

George Washington Chiles served so faithfully for four years that once, when his master was slightly wounded, he “exposed himself to the fire of the enemy and carried him from the battlefield to a place of safety.”

186

John Gregory was so devoted that when his master was killed in action, he accompanied the body home.

187

Although many slaves served diligently as body servants, such a post was sometimes fraught with danger. After a train collision in 1861, for example, a black cook was killed and another had to have his leg amputated below the knee. And a Virginia cook employed by the Forty-fourth North Carolina Infantry was accidentally killed during a manual-of-arms drill in 1863.

Body servants sometimes fought for the South, if given an opportunity, and occasionally replaced white troops. On the few occasions when they encountered black Unionists on the battlefield, black Confederates generally treated them with contempt. In some cases, they seized the servants of Union officers as their personal prisoners. During the battle of Brandy Station in Virginia on June 11, 1863, a Union officer's black servant was captured at gunpoint by body servants with the Twelfth Virginia Cavalry, Tom and Overton, who shared him as their slave. Nonetheless, his fate proved to be better than that of another male Union servant who was captured by Confederate servants. He escaped but was swiftly recaptured. As an expression of their loyalty to the Confederacy, the black servants promptly executed him.

188

According to a white Confederate soldier, when his regiment went into battle, so too, did their servants. They seemed to delight in picking off Federals, particularly black ones. On one charge it was reported that a half-dozen blacks had actually preceded the white troops and had each brought back a black Federal prisoner. They kicked and abused the Federals, saying:

“You black rascal you!âdoes you mean to fight agin white folks, you ugly niggers, you? Suppose you tinks yourselves no âsmall taters' wid dat blue jacket on and dem striped pants. You'll oblige dis Missippi darkey by pulling dem off right smart, if yer doesn't want dat head o' yourn broke” said one of our cooks to his captive; “comin' down Souf to whip de whites! You couldn't stay 't home and let us fight de Yanks, but you must come along too, eh! You took putty good care o' yourself, you did, behind dat ole oak! I was alookin' at yer; and if you hadn't dodged so much, you was a gone chicken long ago, you ugley ole Abe Lincolnite, you!”

189

Indeed, an abundance of evidence points to the fact that on numerous occasions, body servants of the Confederacy actually fought. For instance, one Confederate officer wrote that William, his servant, “fought by my side in more than one affair.”

190

While body servants found their way into combat as circumstances dictated, other black Southerners enlisted, some officially and some surreptitiously, in regular units. Bart Turner, Nat Turner, Dick Berry, and Milt Wiseman all joined the First Arkansas Volunteers, a regiment organized at Helena, of which Patrick R. Cleburne was colonel. They fought at Shiloh, Murfreesboro, Ringgold Gap, Atlanta, and Franklin. In fact, Turner, Berry, and Wiseman were killed in the battle at Franklin.

191

Holt Collier enlisted in a Tennessee regiment and fought his first battle at a bridge over Green River; he eventually served with the Texas Cowboys, Ross's Brigade, and concluded his service under Colonel Dudley Jones.

192

Two black regimentsâone slave, and the other composed of free blacksâtook part in the Battle of Bull Run.

193

Another, Rube Witt, enlisted in the Confederate army in Alexandria, Louisiana, but by the time his regiment was prepared to fight, the war was over.

194

Whereas some slaves volunteered their services to the Confederacy, an even larger number of free blacks volunteered to help. A company of free blacks, for example, in Nashville, Tennessee, offered their services to the Confederate government. Free blacks in Savannah, Georgia, voiced their undying loyalty to the Confederacy in the following letter:

The undersigned free men of color, residing in the City of Savannah and County of Chatham, fully impressed with the feeling of duty we owe to the State of Georgia as inhabitants thereof, which has for so long a period extended to ourselves and families its protection, and has been to us the source of many benefitsâbeg leave, respectfully, in this the hour of danger, to tender to yourself our services, to be employed in the defense of the state, at any place or point, at any time, or any length of time, and in any service for which you may consider us best fitted, and in which we can contribute to the public good.

195

In Richmond in 1861 a company of sixty-three free blacks offered themselves for service,

196

as did free blacks who were members of the New Orleans Native Guards. The Native Guards were composed of proud Creole blacks whose predecessors had served in a free black regiment during the War of 1812, winning the praise of Andrew Jackson for their role in the Battle of New Orleans.

197

Moreover, eighty-two free blacks in Charleston petitioned the state through the mayor “To be assigned any service where we can be useful.”

198

Some blacks, free and enslaved, also served in the Confederate navy. Edward Weeks was a sailor on board the CSS

Shenandoah,

and at least three free blacks served as sailors aboard the CSS

Chicora,

which was used in the defense of Charleston. The CSS

Alabama

had one black crewman, and the Savannah squadron had several blacks. Moses Dallas was the most famous among those in the Savannah squadron. Initially, Dallas enlisted in the Federal army but later deserted and joined the Savannah squadron, where he became “the best inland pilot on the coast.” He led a party of 132 Confederates on a successful attack against a Federal gunboat. Shortly thereafter, he guided the raiders up to the USS

Water Witch

. Military records reported that Dallas was killed in the ensuing battle, but he reappeared three months later as a Union soldier, having joined the 128th U.S. Colored Infantry.

199

A small number of pro-Confederate free blacks and slaves spied for the South under the supervision of Confederate spies such as Belle Boyd or officers such as Colonel John Singleton Mosby. Black Confederate spies often were very proficient in tracking Union troop movements throughout the South. Had Southern whites not displayed so much racial prejudice, in all likelihood they could have garnered even more intelligence information. Like many Union officials, racial prejudice caused many white Confederates to judge blacks as untrustworthy or lacking in the patriotism, brains, skills, and nerve required for the dangerous task of wartime intelligence. Moreover, the efforts of Confederate officials to solicit support from blacks as spies or scouts were hampered by the fact that a significantly larger number of blacks preferred to assist Unionists.

200

As was the case for black Union spies and scouts, the work they engaged in was fraught with danger. If detected, they were executed.

Some free blacks and slaves who did not fight, act as personal servants, or provide intelligence information assisted the Confederate war effort in other ways. For example, Anthony Odingsells, the largest black slaveholder in Savannah, Georgia, sold fish, oysters, meat, and other commodities to Southern troops even after Confederate currency became greatly devalued. With General William Tecumseh Sherman's army swiftly advancing upon the area around Savannah, Odingsells sent his slaves to Fort McAllister to help build fortifications for the impending battle.

201

Likewise, Francis Sasportas, a free black butcher in Charleston, sold meat at reduced prices to the Confederate government to feed the soldiers. One issue of the

Charleston Mercury

reported that “Free Colored men ... contributed $450 to sustain the cause of the South.” The elite Brown Fellowship Society of Charleston voted to donate fifty dollars to defray medical expenses for sick and injured Confederate soldiers, and a group of free black women in the same city collected $450 and presented it to the YMCA for the Confederacy.

202

A black-sponsored ball at Fort Smith, Arkansas, raised money for Confederate soldiers. A Petersburg, Virginia, free black, Richard Kinnard, gave $100, and Jordan Chase, a Vicksburg, Mississippi, free black, donated a horse to the Confederate cavalry and pledged an additional $500. A New Orleans free black real estate broker gave $500 to the war effort.

203

Even though money was in short supply for most slaves, some among this group contributed to the Confederate cause. William, a Virginia slave, patriotically invested $150 in Confederate state bonds, and another Virginia slave donated twenty dollars in cash.

204

Certainly, a lack of money did not prevent those free blacks and slaves who wanted to contribute from doing so. The free black women of Savannah made uniforms for Southern soldiers, and an Alabama slave gave a state regiment a bushel of sweet potatoes.

205

John Jasper, a slave preacher residing in Virginia, ministered to wounded troops in Confederate hospitals.

206

It is not surprising that some black women who assisted the Confederacy were forced to do so, as was the case for many black men. Calvin Moye recalled that his master “had de women folks on de plantation to makes up lots of clothes for de soldiers. I has seed several wagon loads of clothes hauled off from dar at one time.”

207

Kate Crawford, a white owner, remembered that even the youngest of her slaves made sandbags. Another slaveholder recalled the efforts of slave women for a wartime sewing circle that produced only fourteen pairs of drawers in one week.

208

Other black women were forced to work in the hospitals nursing and attending sick soldiers. Whether they were making uniforms, looking after the wounded, or working in any other support role, most black females generally displayed the same lack of enthusiasm for their tasks as did most black males.

209