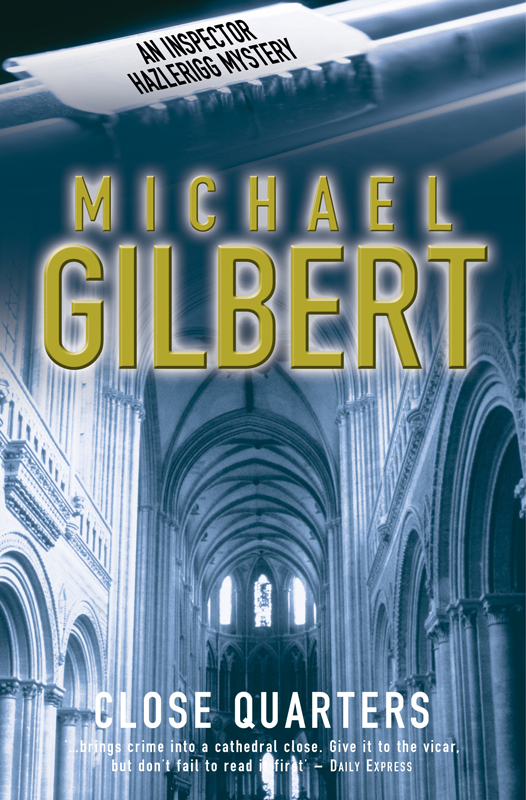

Close Quarters

Authors: Michael Gilbert

Close Quarters

Â

First published in 1947

© Estate of Michael Gilbert; House of Stratus 1947-2012

Â

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of Michael Gilbert to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2012 by House of Stratus, an imprint of

Stratus Books Ltd., Lisandra House, Fore Street, Looe,

Cornwall, PL13 1AD, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

Â

| EAN | Â | ISBN | Â | Edition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0755105060 | Â | 9780755105069 | Â | Print |

| 0755132173 | Â | 9780755132171 | Â | Kindle |

| 0755132173 | Â | 9780755132171 | Â | Epub |

| 0755146573 | Â | 9780755146574 | Â | Epdf |

Â

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author's imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

Â

Â

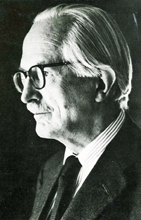

Born in Lincolnshire, England, Michael Francis Gilbert graduated in law from the University of London in 1937, shortly after which he first spent some time teaching at a prep-school which was followed by six years serving with the Royal Horse Artillery. During World War II he was captured following service in North Africa and Italy, and his prisoner-of-war experiences later leading to the writing of the acclaimed novel

âDeath in Captivity'

in 1952.

After the war, Gilbert worked as a solicitor in London, but his writing continued throughout his legal career and in addition to novels he wrote stage plays and scripts for radio and television. He is, however, best remembered for his novels, which have been described as witty and meticulously-plotted espionage and police procedural thrillers, but which exemplify realism.

HRF Keating stated that

âSmallbone Deceased'

was amongst the 100 best crime andmystery books ever published.

“The plot,”

wrote Keating,

“is inevery way as good as those of Agatha Christie at her best: as neatlydovetailed, as inherently complex yet retaining a decent credibility, and asfull of cunningly-suggested red herrings.”

It featured Chief Inspector Hazlerigg, who went on to appear in later novels and short stories, and another series wasbuilt around Patrick Petrella, a London based police constable (later promoted)who was fluent in four languages and had a love for both poetry and fine wine. Othermemorable characters around which Gilbert built stories included Calder and Behrens. They are elderly but quite amiable agents, who are nonetheless ruthless andprepared to take on tasks too much at the dirty end of the business for theiryounger colleagues. They are brought out of retirement periodically uponreceiving a bank statement containing a code.

Muchof Michael Gilbert's writing was done on the train as he travelled from home tohis office in London:

“I always take a latish train to work,” heexplained in 1980, “and, of course, I go first class. I have no trouble inwriting because I prepare a thorough synopsis beforehand.”.

After retirementfrom the law, however, he nevertheless continued and also reviewed for

âTheDaily Telegraph'

, as well as editing

âThe Oxford Book of Legal Anecdotes'

.

Gilbertwas appointed CBE in 1980. Generally regarded as âone of the elder statesmen ofthe British crime writing fraternity, he was a founder-member of the BritishCrime Writers' Association and in 1988 he was named a Grand Master by theMystery Writers of America, before receiving the Lifetime âAnthony' Achievementaward at the 1990 Boucheron in London.

MichaelGilbert died in 2006, aged ninety three, and was survived by his wife and theirtwo sons and five daughters.

TO

CECIL HEWLETT

of Kelowna, Canada

in recognition of the fact that he is the only person mentioned by name

It must have been at about this time, or possibly a little earlier, that Mrs. Mickie had a fright. She was sitting by the fire darning a sock when she heard the front door open with a crash. The wind was now blowing great guns, and thinking that the servant had carelessly left the door unlatched she hurried into the hall. There she stopped in astonishment. Her husband â whom she had imagined to be quietly working in his study â was standing in the doorway, his hair dishevelled, a mackintosh flung loosely round his shoulders, and his face as white as death. He swayed on his feet, and for a moment she had a horrible suspicion that he had been drinking; then she realised, being a woman of some sense, that he had simply been badly frightened.

âWhy, Charles, my dear,' she said quietly, âwhatever has happened? You look as if you'd seen a ghost.'

âI have,' said Mickie slowly.

HOUSEHOLDERS OF MELCHESTER CLOSE

The Rev. Canon Bloss

Late Scholar of Balliol College, Oxford (1st Class Lit. Hum.), 1895. Canon of Melchester and Prebendary of Rowstock Parva. One married daughter.

The Rev. Canon Beech-Thompson, M.A.

Queen's College, Oxford. B.A., 1899, M.A., 1902. Author of

Stained Glass in the Early English Period, Cromwell â Iconoclast,

etc. Canon of Melchester. Married. No surviving children.

The Rev. Canon Trumpington, B.A.

Late Scholar of Wadham College, Oxford. B.A. (2nd Class Lit. Hum.), 1900. Principal of Melset Theological College, Canon of Melchester. Unmarried.

The Rev. Canon Fox

Educated privately. Edinburgh Theological College, 1902-4. Canon of Melchester. Married. Two sons, two daughters.

The Rev. H. H. Hinkey

Vicar Choral and Precentor of Melchester. Rector of St. Crispin's in Melchester. Founder of and contributor to

Cats at Home.

Unmarried.

The Rev. M. J. Malthus

Vicar Choral of Melchester. Chaplain to the Judge in Assize. Hon. Treasurer of “Friends of Melchester Cathedral.” Married. Three children.

The Rev. A. G. Halliday

Vicar Choral of Melchester and assistant

of

Melchester Choir School.

The Rev. E. V. Prynne, M.C., M.A.

Late Scholar of Keble College, Oxford. B.A., 1914. Army Chaplain to the Forces, 1915-18. M.A., 1919. Vicar Choral of Melchester and assistant of Melchester Choir School. Married. One daughter. Wife died, 1930.

C. S. Mickie, Mus. Doc, F.R.C.O.

Organist and Choirmaster

of

Melchester. Until 1930 assistant organist, Starminster. Married. No children.

L. J. Smallhorn, B.A. Cantab.

Headmaster of the Choir School. Associate of the Society for the Preservation of Tombs and Catafalques. Unmarried.

G. H. Scrimgeour

Solicitor. Daniel Reardon and John Mackrell Prizeman. Clerk to the Chapter of Melchester. Late senior partner of the firm of Wracke, Spindrift, and Scrimgeour, Melchester and Starminster. Unmarried.

Mrs. E. A. Judd

Relict of J. D. Judd, D.D., Canon of Melchester, the celebrated author of

Liturgy for the Millions, The Book of Common Prayer done into the Esquimaux Tongue,

etc.

D. Appledown

Head Verger of Melchester. 1887-1900 Deputy Junior Verger. 1900-1 in S. Africa. 1905-14 Junior Verger. 1914 to date: Head Verger. O.B.E. (Civil Division, Coronation award). Unmarried. One brother.

P. H. Parvin

Second Verger. Appointed 1925. Married. One son.

R. Morgan

Third Verger. Appointed 1935. Unmarried.

H. K. Brumfit

Late Sgt. Royal Horse Artillery. Served India, Egypt, Palestine (1915-18). Appointed constable of the Close, 1920. Married. Seven children.

The Dean of Melchester

1

DECANUS VIGILANS

The Dean, as he lay awake in bed that memorable Sunday night, pondered the astonishing vagaries of the weather. He felt, as a personal presence in the room, the oppression of the coming storm. His windows were wide open, and an occasional breath of hot air stirred the curtains. Heavy clouds had been stealing up since early evening, and by this time the night was pitchy black. The chimes, as Melchester cathedral clock struck the half-hour between eleven and midnight, seemed muffled and lethargic.

The Dean turned over in bed for the twentieth time and tried to compose his mind. But his mind refused most obstinately to be composed. And he had a feeling that the elements which troubled it were not entirely atmospheric. The approaching storm magnified and made more oppressive troubles which had been lying in wait, and which needed only this occasion to pop up their confounded heads. Feeling certain that he would get no sleep until the storm broke or passed on, the Dean reluctantly brought himself to consider affairs in general. What was wrong with the Close? In the fourteen years that he had been there he could remember no time of such concentrated irritation and unease. First and foremost, of course, this extraordinary persecution of Appledown, the head verger. It had started over a week ago with anonymous letters. These epistles, typewritten and uniformly abusive, had been received by most of the Close community. The Dean himself had not been favoured, but the Precentor had shown him one which he had found amongst his mail on the previous evening. It was a fair specimen of the anonymous writer's style, and had stated in terms which, despite a liberal classical education, had caused the Dean to clear his throat rapidly, that Appledown was not only inefficient but also immoral â indeed, quite remarkably immoral, the Dean could not help thinking, for a man of nearly seventy.

The postmark had been Starminster â a small market town nearly thirty miles from Melchester â but that this was the merest blind had been made manifest by the disgraceful incidents of the previous Wednesday. The wolf was indeed within the fold.

Melchester, like most other English cathedrals, had its own resident choir school. The sixteen cathedral trebles were housed in two fine Queen Anne buildings standing in the south-west corner of the Close. Wednesday had been the Headmaster's birthday. Such a day was traditionally an excuse, the Dean reflected morosely, for a good deal of unnecessary licence and excess. An extra half-holiday was inevitable; superfluous food was consumed and superfluous spirits were let off. However, the day's proceedings usually began quietly enough. Morning prayers (weather permitting) were held in the forecourt, and at their termination the school flag (a curious confection of primary colours) was hoisted to the top of the flagstaff by the head boy. This impressive ceremony duly took place in the presence of the Dean, a scattering of Close worthies, and such errand boys as felt disposed to linger on their morning rounds, but was rather marred by the fact that when the flag floated out in the morning breeze it revealed â stitched in white bunting and painfully visible â the words “

BOOZY OLD APPLEDOWN

.”

Needless to say, this irreverent legend was taken in very good part by the younger members of the audience, and it was with obvious reluctance that they watched the flag being lowered whilst the offending stitches were cut away. It had been apparent to the Dean that the senior verger, worthy man though he might be, was not over popular with the cathedral choristers. But equally apparent to anyone who knew anything of the curious workings of a boy's mind, was that none of them were accessory to the joke. Their surprise had been genuine and their appreciation entirely spontaneous.

There had been a further show at Evensong. The copies of the anthem, when opened, had shed a shower of leaflets, all typewritten, and all harping on the same note. “Appledown is past his job” had been the theme of the unknown letter-writer on this occasion. It was curious, the Dean reflected, the psychological effect which a manoeuvre of this sort produced. It had crossed his mind more than once in the past six months that Appledown

was

getting old for his work. It was a responsible post, being head verger of a cathedral, and in Parvin, the second verger, they had a younger man well trained to fill the position.

Immediately, however, the anti-Appledown campaign had begun, his feelings veered strongly. The natural reaction to such an underhand assault had been a strong caucus of pro-Appledown opinion. Sympathy and sentiment had united to condemn cowardly tactics, and far from weakening it the whole affair had strengthened the head verger's position considerably. It might even, reflected the Dean grimly, result in Appledown keeping his post some years longer than he would otherwise have done â after he really

was

past it, in fact. This example of the working of Providence the Dean felt to be vaguely comforting, and he settled himself into a fresh position in bed.

There had been other troubles. Why did Malthus always want to be running off at a moment's notice? Malthus was the second of the three vicars choral, and for two weeks out of every six it was his duty to sing morning and evening service in the cathedral. He had other jobs, of course, but what he did for four weeks was his own business. What the Dean objected to was his desertion of his post during the remaining two.

Of course, he had come and asked for permission, but that made it worse, in a way. Almost as if he were pushing the responsibility on to the Dean. Malthus had tackled him in the vestry after Matins that morning. Prynne wouldn't mind taking Evensong for him, and Matins on Monday. His sister was ill, in the country. He must see her. He was sure Prynne wouldn't mind.

The Dean himself was far from sure. In fact, he was pretty certain that Prynne would mind. A feature almost as disturbing to the Dean as the constant absence of second Vicar Choral Malthus was the constant presence of senior Vicar Choral Prynne. Whenever he thought of him â which was frequently â the Dean was reminded of the words in which Milton (his favourite poet) describes Belial at the council of the infernal powers:

“⦠whose tongue

Dropt manna and could make the worse appear

The better reason to perplex and dash

Maturest counsel.”

Decidedly Ernest Vandeleur Prynne, though an able man, as the Dean reluctantly admitted, had proved a sore trial to more than one member of their community.

âHalliday will be back by midday on Tuesday,' Malthus had gone on, âand he won't mind taking over the services for the next day or two.' Of course Halliday wouldn't mind, or anyway he wouldn't say so if he did mind. A bit rough on him though, having to cut short his holiday and come back to help Malthus out of a hole. Good chap Halliday, cut short holiday, Halliday's holiday, holiday for Halliday, Halliday ⦠holiday. Hobday ⦠Halliday â¦

The Dean, despite the oppression in the atmosphere, which seemed, if possible, to have increased during the last few minutes, was on the point of dropping off when a vivid flash of lightning lit up the room and caused him to sit bolt upright in bed. It was not, of course (absurd!) that he was afraid of a thunderstorm, but from boyhood's day he had been, as he put it to himself, more susceptible to their influence than most people. He had counted twenty as fast as he dared before the thunder rolled out, and comforting himself (for he was a firm believer in that particular piece of mumbo-jumbo) with the conclusion that the storm was still twenty miles distant, he lay down again and composed himself once more to sleep.

When all else failed he had still one card to play â one homemade panacea to try. Where other people wooed sleep by counting sheep jumping over a stile, the Dean had often found it efficacious to picture the members of his Chapter as they passed through the choir gates on their way to service. First came the inscrutable Canon Bloss. Canon Bloss had a peculiar aptitude (which the Dean had formerly imagined to be confined to Grand Lamas and Victorian ladies' maids) of progressing without appearing to move his feet. Taken all in all, Canon Bloss was not unlike some Tibetan dignitary in appearance â perhaps some rotund and faintly human idol of the middle Buddhist period, with a good deal of dignity and a number of superfluous stomachs and chins.

Behind him ambled Canon Beech-Thompson, demonstrating both by walk and carriage how inevitable it was that he should be known to a select circle as “Jumbo” Beech-Thompson.

It was with greater tolerance that his mind's eye took in Canon Trumpington, third in the procession. He could not conceal it from himself that he liked Canon Trumpington, unprecedented though it might be for a Dean to entertain such sentiments towards another member of the Chapter.

âTake him all in all,' murmured the Dean, gagging a little, âas just a man as e'er my conversation coped withal. A sweet-faced man. As proper a man as one shall see in a summer's day.'

After him Canon Fox appeared as rather an anti-climax. An indefinite person, Canon Fox. He appeared and disappeared as unostentatiously as his animal namesake. Of course he hadn't been at Melchester very long, and no one knew much about him. Canon Fox. Shivering shocks. Iron locks. Box and Cox. The Dean was nodding again. Canon Fox (a deadly association of ideas flicked across his mind) hadn't been there long. He had come ⦠now when had he come? A year ago, no more. And why had he come? For a moment his sleepy brain refused to deal with the subject. Why should a new canon come to Melchester? At that moment an icy shudder ran down the Dean's back. It was almost as if a real voice had whispered the answer: âHe came because Canon Whyte had died.'

At that moment a second brilliant flash of lightning filled the room, throwing every detail into sharp relief. A moment later and the thunder again rolled out. Nearer and more menacing. But this time it seemed to be muttering, âDied ⦠died ⦠fell from the roof and died.'

The Dean felt something roll down his cheek, and putting his hand to his forehead he found that it was wet.

What, in heaven's name, the Dean asked himself fretfully, had brought that business into his mind at such a particularly unsuitable moment? He was convinced now that he would get no sleep at all that night. The death of Canon Whyte had been very upsetting. Nothing mysterious or really sensational about it, mind you. Nothing â with considerable distaste the Dean formulated the exact word in his mind â nothing “police-court” about it. Just simply upsetting for all concerned, for Canon Whyte's family, and his colleagues on the Chapter, and for Canon Whyte too, of course.

It had all happened more than a year ago. Melchester Cathedral, like many others, was a great centre and an attraction for tourists, in the summer months especially. But the ordinary tourist had perforce to confine his attentions to the more easily accessible parts of the building: the nave, transepts, and choir; the beautiful Lady Chapel and the stately cloisters; the old Chapter House.

But if you could induce one of the vergers to accompany you, you might penetrate the dark little door in the south-west angle and climb up a spiral of well-trodden stone steps. This brought you out on to the clerestory â further steps, and a very low doorway, and then you were outside, in a narrow gallery which had been originally built for the convenience of the workmen who put the first roof on Melchester Cathedral, more than five hundred years before. This gallery, invisible from below, ran right round the roof, and it was from this gallery one sunny morning in early September that Canon Whyte had fallen â a hundred and three measured feet â on to the flagstones in front of the newly erected shed which housed the electric motor which supplied the power for the famous Melchester organ.

It was â the Dean thought of it with a grimace â the only time in the sixty-five years of a sheltered life that he had been brought face to face with the unpleasant reality of violent dissolution. His first thought had been that it was uncommonly messy. A scared and breathless verger with a message that Canon Whyte had fallen and hurt himself had brought him on the scene quite unprepared for the realities of the case. When he had rounded the corner of the Chapter House and seen what was to be seen on the sunlit stones, it was by a firm exercise of control that he had prevented himself from being actually sick. A moment of shock will sometimes etch a scene indelibly on the mind, and he had only to shut his eyes to see it again. The towering grey walls, dwarfing the little engine shed. The respectful but interested faces, of the three vergers; the flat grey stones; the huddled body; blood and the smell of warm tar. He didn't want to think about that. Above them all, two incongruous pigeons preening themselves and cooing.

Accidental death. Naturally. A coroner's verdict had certified so. Canon Whyte very often took parties of adventurous visitors on a ramble round the outside gallery, pointing out the many interesting terminal carvings and gargoyles so characteristic of the period and the building. In fact he had made a special study of them. The coroner had been informed that he was writing a book on the subject. Well, not exactly a book â a brochure. Anyway, he was often up there alone or with visitors. The parapet was high, of course. The coroner had not been up there himself but he had some measurements. Four feet and four inches from the level of the leading. The jury would appreciate that this would come well up to the chest level of an ordinary man. But of course at such a height it was easy to lose one's head. One got giddy. They had heard, no doubt, of people without much head for heights who could not bring themselves within many feet of the top of a precipice or cliff; they entertained a fear that a fit of vertigo brought on by the contemplation of a great depth beneath them might cause them to lose control. No doubt something of the sort had happened here.

In answer to some tactful but obviously leading questions it was established that Canon Whyte had been perfectly happy. That he was an exceptionally sane and balanced man. No, certainly not, he had left no “note” or letter of any kind, or of course the jury would have had it read to them.