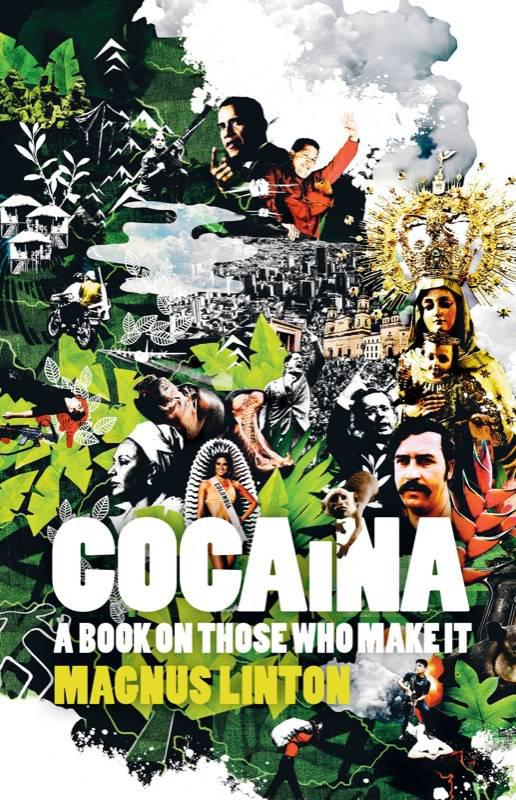

Cocaina: A Book on Those Who Make It

Read Cocaina: A Book on Those Who Make It Online

Authors: Magnus Linton,John Eason

Tags: #POL000000, #TRU003000, #SOC004000

Scribe Publications

COCAÍNA

Magnus Linton is a Swedish writer whose work tackles controversial social, political, and ethical topics. He is the author of several acclaimed non-fiction books, including

The Vegans

(2000), a provocative account of the ethics of eating meat that turned then Swedish prime minister Göran Persson into a ‘semi-vegetarian’;

Americanos

(2005), a pioneering masterpiece exploring the rise of neo-socialism in Latin America; and

The Hated

(2012), which examines the emergence of the new radical right in Europe.

Cocaína

was first published in Swedish in 2010 and was nominated for the August Prize, Sweden’s most important literary award. Magnus lives in Stockholm and Bogotá with his family.

John Eason is an American translator and educator based in Stockholm. He holds a PhD in Scandinavian Studies from the University of Wisconsin, where he has taught Scandinavian literature and Swedish. John has also been a guest lecturer at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

Scribe Publications Pty Ltd

18–20 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria, Australia 3056

Email: [email protected]

First published in Swedish by Atlas Bokförlag in 2010

First published in English by Scribe 2013

Published by agreement with the Kontext Agency

Copyright © Magnus Linton 2010, 2013

Translation copyright © John Eason 2013

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

While every care has been taken to trace and acknowledge copyright, we tender apologies for any accidental infringement where copyright has proved untraceable and we welcome information that would redress the situation.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data

Linton, Magnus, author.

Cocaína: a book on those who make it / Magnus Linton; translated by John Eason.

9781922072238 (e-book.)

1. Cocaine industry. 2. Drug traffic. 3. Drug control. 4. Drugs of abuse.

Other Authors/Contributors: Eason, John, translator.

363.45

scribepublications.com.au

To Sid and Elina

CONTENTS

1

Cocaturismo

: Medellín as heaven

2

Green Gold

: the carousel of war

3

Pablo’s Party

: the State gets cancer

4

The War on Drugs

: from Nixon to Obama

5

Mañana

: the future of the powder

PREFACE

ON THE EVENING

of 18 August 1989, I was in a taxi in Bogotá, on the way to meet a friend. The car was cruising down the colonial quarter, dodging potholes, but it was not until the headlights swept across the road as we crossed Avenida Jiménez that I was able to get a good look, and I realised the city centre was dead. No one was hanging out by the statue in the park; no one but

los gamines

, street kids, sitting around like lifeless shadows with their noses stuck in bags, inhaling glue in an effort to numb their bodies against the impending cold of the night.

‘

¡

Mataron a Galán

!

Galán’s been murdered,’ said the driver.

Luis Carlos Galán was a liberal left-wing politician running for president in the upcoming 1990 election, and he had been the clear frontrunner. He had promised to reform Colombia’s backward landownership structure, but first and foremost he had attacked the way the elite was protecting a man who would go down in history as one of the most bloodstained mobsters of all times: the ‘King of Cocaine’, Pablo Escobar Gaviria.

We continued across the city. I wanted to keep talking about the murder, but the driver just shrugged his shoulders and dropped his head in what I would later recognise as a very common Colombian gesture. At the same time he uttered two words, a phrase that I would one day come to understand as a verbal accompaniment to the gesture. When poor Colombians say

lo mataron

— literally ‘they murdered him’, but meant more in the sense of ‘he was murdered’ so as to avoid the agent — they make a dismissive gesture in which the neck muscles relax, causing the head to drop. The motion signifies that the topic is closed for discussion; that you have touched on an issue foreigners seem unable to understand: the fact that almost everyone in Colombia has a friend or relative who has been murdered. A child. A parent. A friend. A sibling. It is a collective experience.

But in this case, the comment was not made in relation to a family member but about a presumptive president. Consequently, in this context the words and the gesture took on a less personal, more public meaning. It quite simply established the fact that what had happened was not at all unexpected, as in this country most big conflicts end in not just one murder but several.

When I continued to question the driver about what he thought had happened, he only ever answered me with those same two words, and at my destination I silently handed him a roll of pesos and got out of the car. He drove off, but his stiff answer had left me hanging with all my naïve questions about the elusive agents of Colombia. ‘

Lo mataron.

’

ONE DAY IN

the 1990s, I went along with a Colombian friend, Alfonso, to buy a gram of

perico

— cocaine — in western Bogotá. It was a typical middle-class neighbourhood, where families in some of the two-storey houses had

tiendas

: little kiosk-like shops in a front room on the ground floor, where they sold cigarettes and staple foods. We entered one of them, and Alfonso asked the young man sorting through packets of gum behind the counter if the ‘philosopher’ was home.

The guy nodded in the affirmative. ‘

Sí

. In the bedroom upstairs.’

The question was superfluous, as Alfonso well knew, since the philosopher was paraplegic and could not leave the house. But Colombians are the politest people in the world, and an aspect of their good behaviour is to never take anything for granted.

As we entered the living quarters I winced when I saw who was sitting there, but Alfonso quietly assured me that everything was okay. Four policemen were chatting around the dinner table, feasting on a chicken, and the philosopher’s wife was joking with the uniformed men in a familiar way while she assisted the maid to serve them.

‘Good evening; good evening.’ We greeted everyone as we circumnavigated the party and scuttled up a flight of stairs.

The bedridden philosopher, whose lifeless limbs were covered by a heavy layer of blankets, was flipping through the afternoon-television soap operas. He was somewhere between 60 and 70. Alfonso asked him how he was doing, and he responded with a wisecrack before asking, ‘How many?’

Alfonso held up his index finger.

The philosopher pulled a white envelope out from behind a burgundy silk pillow, placed it on the blanket before him, and accepted the cash.

We went downstairs and made another lap around the officers, wishing them

bon appétit

. ‘

Gracias

,’ they said in unison.

IN SPRING 2007

I had a temporary job with a Swedish aid organisation in Bogotá. We had arranged, along with other non-government organisations, a lobbying meeting with one of the most powerful diplomats in the country: Adrianus Koetsenruijter, the head of the European Commission delegation to Colombia.

The purpose of the meeting was to find out the European Union’s opinion on the human-rights situation in the country. New statistics indicated that the number of displaced people in ‘the world’s longest ongoing armed conflict’ was rapidly approaching four million, and everyone was aware that the cocaine industry had become the primary driving force behind the war. Broadly speaking, the guerrillas controlled the coca-growing peasants, the paramilitary groups controlled the higher levels of cocaine production, and the government waged war on the guerrillas (with support from the US military) under the banner of ‘the war on drugs’; it was a strange triangle of combat, in which all the weapons were financed by some facet of cocaine production.

Koetsenruijter was in high spirits. He was about to resign and was pleased to be doing so, as a new job awaited him in another part of the world. We happened to catch him during some downtime, when he felt he could relax and speak off the record. He said it would be refreshing not to have to put on diplomatic airs anymore. But to be on the safe side, he requested that our conversation go no further, and we nodded in agreement.

He spoke from the heart. In his opinion, the sitting right-wing government had been good for Colombian society in many ways: cities were safer, people were more inclined to report attacks by armed groups, and there was even a left-wing party in Congress whose representatives could speak out without fear of being murdered. Yet when asked the key question — whether this progress was sustainable — he gave a deep sigh. ‘No.’

And then he said something I have often heard from people in Colombia, but never from a top-ranking EU official. ‘Legalisation. There’s no other option. I don’t know a single person in any high-ranking political post any longer who isn’t in favour of legalising drugs. But that, of course, is politically impossible.’