Collected Prose: Autobiographical Writings, True Stories, Critical Essays, Prefaces, Collaborations With Artists, and Interviews (48 page)

Authors: Paul Auster

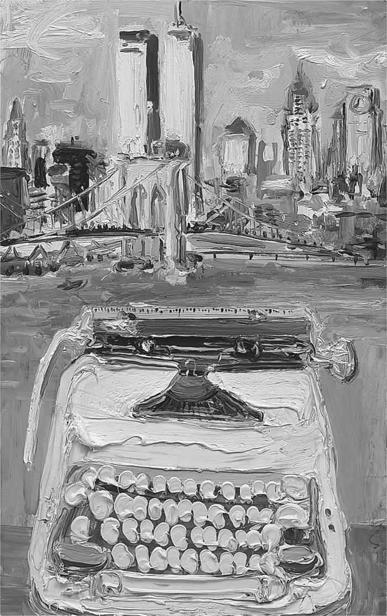

Messer seldom goes anywhere without a sketchbook. He draws constantly, stabbing at the page with furious, rapid strokes, looking up from his pad every other second to squint at the person or object before him, and whenever you sit down to a meal with him, you do so with the understanding that you are also posing for your portrait. We have been through this routine so many times in the past seven or eight years that I no longer think about it.

I remember pointing out the typewriter to him the first time he visited, but I can’t remember what he said. A day or two after that, he came back to the house. I wasn’t around that afternoon, but he asked my wife if he could go downstairs to my work room and have another look at the typewriter. God knows what he did down there, but I have never doubted that the typewriter spoke to him. In due course, I believe he even managed to persuade it to bare its soul.

*

He has been back several times since, and each visit has produced a fresh wave of paintings, drawings, and photographs. Sam has taken possession of my typewriter, and little by little he has turned an inanimate object into a being with a personality and a presence in the world. The typewriter has moods and desires now, it expresses dark angers and exuberant joys, and trapped within its gray, metallic body, you would almost swear that you could hear the beating of a heart.

I have to admit that I find all this unsettling. The paintings are brilliantly done, and I am proud of my typewriter for proving itself to be such a worthy subject, but at the same time Messer has forced me to look at my old companion in a new way. I am still in the process of adjustment, but whenever I look at one of these paintings now (there are two of them hanging on my living room wall), I have trouble thinking of my typewriter as an

it

. Slowly but surely, the

it

has turned into a

him

.

*

We have been together for more than a quarter of a century now. Everywhere I have gone, the typewriter has gone with me. We have lived in Manhattan, in upstate New York, and in Brooklyn. We have traveled together to California and to Maine, to Minnesota and to Massachusetts, to Vermont and to France. In that time, I have written with hundreds of pencils and pens. I have owned several cars, several refrigerators, and have occupied several apartments and houses. I have worn out dozens of pairs of shoes, have given up on scores of sweaters and jackets, have lost or abandoned watches, alarm clocks, and umbrellas. Everything breaks, everything wears out, everything loses its purpose in the end, but the typewriter is still with me. It is the only object I own today that I owned twenty-six years ago. In another few months, it will have been with me for exactly half my life.

*

Battered and obsolete, a relic from an age that is quickly passing from memory, the damn thing has never given out on me. Even as I recall the nine thousand four hundred days we have spent together, it is sitting in front of me now, stuttering forth its old familiar music. We are in Connecticut for the weekend. It is summer, and the morning outside the window is hot and green and beautiful. The typewriter is on the kitchen table, and my hands are on the typewriter. Letter by letter, I have watched it write these words.

July 2, 2000

NORTHERN LIGHTS

Pages for Kafka

on the fiftieth anniversary of his death

He wanders toward the promised land. That is to say: he moves from one place to another, and dreams continually of stopping. And because this desire to stop is what haunts him, is what counts most for him, he does not stop. He wanders. That is to say: without the slightest hope of ever going anywhere.

He is never going anywhere. And yet he is always going. Invisible to himself, he gives himself up to the drift of his own body, as if he could follow the trail of what refuses to lead him. And by the blindness of the way he has chosen, against himself, in spite of himself, with its veerings, detours, and circlings back, his step, always one step in front of nowhere, invents the road he has taken. It is his road, and his alone. And yet on this road he is never free. For all he has left behind still anchors him to his starting place, makes him regret ever having taken the first step, robs him of all assurance in the rightness of departure. And the farther he travels from his starting place, the greater his doubt grows. His doubt goes with him, like breath, like his breathing between each step — fitful, oppressive — so that no true rhythm, no one pace, can be held. And the farther his doubt goes with him, the nearer he feels to the source of that doubt, so that in the end it is the sheer distance between him and what he has left behind that allows him to see what is behind him: what he is not and might have been. But this thought brings him neither solace nor hope. For the fact remains that he has left all this behind, and in all these things, now consigned to absence, to the longing born of absence, he might once have found himself, fulfilled himself, by following the one law given to him, to remain, and which he now transgresses, by leaving.

All this conspires against him, so that at each moment, even as he continues on his way, he feels he must turn his eyes from the distance that lies before him, like a lure, to the movement of his feet, appearing and disappearing below him, to the road itself, its dust, the stones that clutter its way, the sound of his feet clattering upon them, and he obeys this feeling, as though it were a penance, and he, who would have married the distance before him, becomes, against himself, in spite of himself, the intimate of all that is near. Whatever he can touch, he lingers over, examines, describes with a patience that at each moment exhausts him, overwhelms him, so that even as he goes on, he calls this going into question, and questions each step he is about to take. He who lives for an encounter with the unseen becomes the instrument of the seen: he who would quarry the earth becomes the spokesman of its surfaces, the surveyor of its shades.

Whatever he does, then, he does for the sole purpose of subverting himself, of undermining his strength. If it is a matter of going on, he will do everything in his power not to go on. And yet he will go on. For even though he lingers, he is incapable of rooting himself. No pause conjures a place. But this, too, he knows. For what he wants is what he does not want. And if his journey has any end, it will only be by finding himself, in the end, where he began.

He wanders. On a road that is not a road, on an earth that is not his earth, an exile in his own body. Whatever is given to him, he will refuse. Whatever is spread before him, he will turn his back on. He will refuse, the better to hunger for what he has denied himself. For to enter the promised land is to despair of ever coming near it. Therefore, he holds everything away from him, at arm’s length, at life’s length, and comes closest to arriving when farthest from his destination. And yet he goes on. And from one step to the next he finds nothing but himself. Not even himself, but the shadow of what he will become. For in the least stone touched, he recognizes a fragment of the promised land. Not even the promised land, but its shadow. And between shadow and shadow lives light. And not just any light, but this light, the light that grows inside him, unendingly, as he goes along his way.

1974

The Death of Sir Walter Raleigh

The Tower is stone and the solitude of stone. It is the skull of a man around the body of a man—and its quick is thought. But no thought will ever reach the other side of the wall. And the wall will not crumble, even against the hammer of a man’s eye. For the eyes are blind, and if they see, it is only because they have learned to see where no light is. There is nothing here but thought, and there is nothing. The man is a stone that breathes, and he will die. The only thing that waits for him is death.

The subject is therefore life and death. And the subject is death. Whether the man who lives will have truly lived until the moment of his death, or whether death is no more than the moment at which life stops. This is an argument of act, and therefore an act which rebuts the argument of any word. For we will never manage to say what we want to say, and whatever is said will be said in the knowledge of this failure. All this is speculation.

One thing is sure: this man will die. The Tower is impervious, and the depth of stone has no limit. But thought nevertheless determines its own boundaries, and the man who thinks can now and then surpass himself, even when there is nowhere to go. He can reduce himself to a stone, or he can write the history of the world. Where no possibility exists, everything becomes possible again.

Therefore Raleigh. Or life lived as a suicide pact with oneself. And whether or not there is an art—if one can call it art—of living. Take everything away from a man, and this man will continue to exist. If he has been able to live, he will be able to die. And when there is nothing left, he will know how to face the wall.

It is death. And we say “death,” as if we meant to say the thing we cannot know. And yet we know, and we know that we know. For we hold this knowledge to be irrefutable. It is a question for which no answer comes, and it will lead us to many questions that in their turn will lead us back to the thing we cannot know. We may well ask, then, what we will ask. For the subject is not only life and death. It is death, and it is life.

At each moment there is the possibility of what is not. And from each thought, an opposite thought is born. From death, he will see an image of life. And from one place, there will be the boon of another place. America. And at the limit of thought, where the new world nullifies the old, a place is invented to take the place of death. He has already touched its shores, and its image will haunt him to the very end. It is Paradise, it is the Garden before the Fall, and it gives birth to a thought that ranges farther than the grasp of any man. And this man will die. And not only will he die–he will be murdered. An axe will cut off his head.

This is how it begins. And this is how it ends. We all know that we will die. And if there is any truth we live with, it is that we die. But we may well ask the question of how and when, and we may well begin to ask ourselves if chance is not the only god. The Christian says not, and the suicide says not. Each of them says he can choose, and each of them does choose, by faith, or the lack of it. But what of the man who neither believes nor does not believe? He will throw himself into life, live life to the fullest of life, and then come to his end. For death is a very wall, and beyond this wall no one can pass. We will not ask, therefore, whether or not one can choose. One can choose and one cannot. It depends on whom and on why. To begin, then, we must find a place where we are alone and nevertheless together, that is to say, the place where we end. There is the wall, and there is the truth we confront. The question is: at what moment does one begin to see the wall?

Consider the facts. Thirteen years in the Tower, and then the final voyage to the West. Whether or not he was guilty (and he was not) has no bearing on the facts. Thirteen years in the Tower, and a man will begin to learn what solitude is. He will learn that he is nothing more than a body, and he will learn that he is nothing more than a mind, and he will learn that he is nothing. He can breathe, he can walk, he can speak, he can read, he can write, he can sleep. He can count the stones. He can be a stone that breathes, or he can write the history of the world. But at each moment he is the captive of others, and his will is no longer his own. Only his thoughts belong to him, and he is as alone with them as he is alone with the shadow he has become. But he lives. And not only does he live—he lives to the fullest that his confines will permit. And beyond them. For an image of death will nevertheless goad him into finding life. And yet, nothing has changed. For the only thing that waits for him is death.