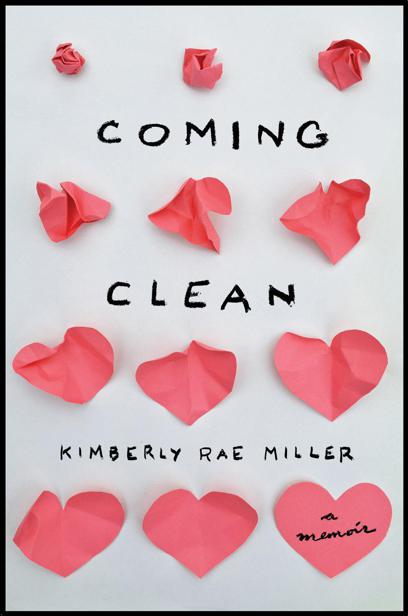

Coming Clean: A Memoir

Read Coming Clean: A Memoir Online

Authors: Kimberly Rae Miller

Copyright © 2013 by Kimberly Rae Miller

Jacket art and design by Lynn Buckley

Author photograph © Chris Macke

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Amazon Publishing

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN-13: 9781477849224

ISBN-10: 147784922X

To Mom and Dad, I love you bigger than the world.

What shames us, what we most fear to tell, does not set us apart from others; it binds us together if only we can take the risk to speak it.

—

STARHAWK

a

I

HAVE A BOX

where I keep all of the holiday and birthday and just-because cards that my friends and family send me. They are memories, tokens of love and thoughtfulness, and there is a part of me that can’t bear to throw them out.

I don’t need these cards. I hardly ever open that box, and so they don’t add anything to my life, but there is a part of me that thinks that maybe, just maybe, one day I will need to remember the moments and people they represent.

This is as close as I can come to understanding the way my father thinks. He loves paper and pens and radios and things that are broken and things that are cheap and things that remind him of things that he once liked and things that remind him of me and of things that I once liked—in that same can’t-bear-to-let-it-go way I feel about those cards. He sees a thousand tangential futures for a broken radio, articles he has yet to read in a nine-year-old issue of the

New York Times,

and one specific memory for that glittery purple pencil he writes notes in his planner with. He used a similarly purple pencil that one time I came home crying from school because I couldn’t write a lowercase

A

. I sat

on his lap and we spent what felt like hours writing little

O

s with tails until I finally mastered the art of the

a.

My father is a hoarder. I can say that now, and people’s eyes widen in understanding. Maybe they know someone who is a hoarder, or maybe they throw that word around to describe their messy roommate, but

hoarder

is now a part of our common vernacular.

As ubiquitous as it may seem, it’s still a relatively new word. When I was growing up, there was no defining term for why my father loved stuff so much. I certainly couldn’t imagine anyone else in the world living the way my family did. None of my friends abandoned entire rooms of their house to the things that lived there. They weren’t pushed off couches or beds by piles of clothes and papers and knickknacks, with the resolution to find somewhere else to sit or sleep in the future.

I stopped thinking about the house I grew up in almost as soon as I left it at eighteen. I didn’t forget or block it out; I just simply decided not to remember. By that time my parents were in a new home—a messy, more than messy, but not as messy home. And then eight years of not-remembering later, in the middle of my clean little grown-up life, I started having nightmares.

In these dreams I am always gearing up to clean. I don’t know where to start and so I do what I always do when I want to avoid work: I go get a snack. In one particular dream I am trudging barefoot through the downstairs hallway, then the den, and eventually the kitchen. I can feel the wet mashed newspapers between my toes, not so different from the way sand feels as you inch closer to the ocean. I tiptoe around the debris in my path, conscious that there is probably something sharp amidst

the sludge, paper, and old clothing. As I rummage through the kitchen I am keenly aware that I do not want to open the refrigerator. It has been abandoned for years, and what exists inside is a soupy mess of rotting food. Instead, I scour the counter for packaged foods. In the bread box there is what was once a loaf of Wonder Bread, but is now a shrunken heap of moss and maggots. Ramen soup is safe, I think, but when I open the package there are bugs inside that, too.

The bugs don’t faze me in my dream, as they didn’t faze me in my adolescence, and I put the bug-infested bag of soup mix back on the counter. I don’t throw it out because there’s really no point anymore.

It’s not always the kitchen. Sometimes I’m in the bathroom, or the hallway, or the living room. Each room has its own particular flavor of squalor, but what remains constant is that I am always trying to figure out where and how to start to fix it.

These are the kind of dreams that jar me from my sleep in the middle of the night. My mind doesn’t always catch up with my body, and it takes me a minute or so to realize that I’m not at the house in the middle-class suburbs of Long Island that I grew up in but the small, neat Brooklyn apartment I have called home for the whole of my adult life. My first instinct, once my bearings have been located, is to call my mom. She is quite possibly the only person who understands how deeply these scars run, and I need her to tell me that this is not my life anymore, and that it never will be again. I know she will, and then she will apologize, as she always does. She has been apologizing for as long as I can remember, but I can never forgive her enough for her to forgive herself. She has always been afraid of dreams like these, afraid that a last straw would come along and I would stop loving her.

She has warned me, “One day you won’t be able to pretend everything was okay, and you’re going to hate us.”

My mother is right more often than not, and she is right that everything was not okay. The memories are still there in the place in my mind I put them years ago, but the person in them doesn’t feel like me at all. She feels like a younger sister, someone close to me, someone I want to reach out to, to tell her that her world will be better. And cleaner. I’ve been there, I’ve seen it, and it turns out normally ever after for her.

But my mother is wrong about one thing: I do not hate her or my father. Sure, I remember the dirt and the rats and the squalor, but I also remember parents who loved me. Doting, fallible people who gave me everything they had, and a whole lot more.

ONE

H

E HAD ONE PLASTIC BAG

tied to another tied to a torn knapsack and rested it all on his shoulders. This man was mesmerizing. This man was homeless. I had never thought about homeless people before, but I knew that was what he was.

I craned my neck backward to watch him, my mother pulling me toward our gate, as he walked through Penn Station and ate the remnants of a box of Kentucky Fried Chicken. I wondered how he had paid for his chicken and watched as his plastic bags swayed from side to side with each of his steps.

When he saw me staring he tilted his box of chicken toward me in offering, and I immediately looked away and ran to catch up with my mother. I didn’t look back, but I thought about him the whole ride home.

“Are you feeling okay?” My mom asked as she bent over to kiss my forehead. “You don’t have a fever.”

I wasn’t usually quiet, at least not around my parents, and whenever I was speechless for more than a few minutes at a time my parents assumed that I wasn’t feeling well. I nodded my head to indicate that I was fine. I wasn’t, but the bad feeling wasn’t

sickness—it was something else. The man in the train station, with his tattered appearance, bags of trash, and kind offering, reminded me of my father.

My dad wasn’t like other people. He didn’t follow the rules that seemed to govern other grown-ups, and the priorities that he tethered himself to were ideas and knowledge, mostly in the form of newspapers and books, reinforced by a steady soundtrack of NPR. He did the things that other adults did: He had a family, he had a job, but even when I was a little girl they seemed to me like accidental realities he had stumbled into.