Compartment No 6 (16 page)

Authors: Rosa Liksom

She woke to the hideous shriek of a song thrush. She watched from her mattress as Gafur and the people of the yurt gnawed at mutton, without greed or any great gusto, and gulped down

kumis.

She was careful not to step on the threshold when she went outside. The gentle silence of the night greeted her. The seething sun had set behind the Golden Mountains and the sky gradually was lit with a thousand dry, restless stars. They swept across the blue space, the Milky Way zigzagging fitfully above the mountains, galaxies hissing over the village of yurts. She sat down on a stone, touched its cold surface. The stone was silent. She watched the song thrush torment the tethered falcon.

In the morning her eyes hurt again. Her head was splitting; there was an unbearable cosmic roar in her ears. Her shoulders slumped, her head hung limply.

The bright icy sun didn't ask forgiveness. In the summer, that same sun dried up the raindrops before they could reach the earth. A stinging icy wind flowed from the north, dragging a mountain crow and a tattered burlap sack with it. Frost laid down by the night's freeze grew from the ground up the walls of the yurt. Thin black trails of smoke floated sleepily through the air.

The girl stood still. From the east a piercing brightness came, in the west a thick grey gelatinous fog swirled, and in the north, at the northern edge of the sky, hung a blood-red comet. It looked like an old 1930s decal glued to a paper sky stained with dark-blue ink. She marvelled at a flock of cranes that stepped in a phalanx along the level ground, pecking up dead grasshoppers from the autumn before. She saw five black long-haired bulls. They were scraping the ice with their hooves to find the grass beneath. She heard the goats bleating and strolled towards a grove of frosty, sad-hanging branches. The women were milking the goats.

Gafur appeared out of nowhere, lively, enjoying his fix, capering over the hard-frozen snow in his dandy's pointy-toed shoes, and followed a Mongolian man to where the horses were. They took the harnesses of two restive horses and led them out in front of the yurt. They were on their way to look for a half-tamed flock of sheep that had disappeared during the night.

She walked to the edge of the bubbling river. From there she could see the wooden fence of the corral, which was empty now. A small mongrel dog followed her. White steam rose from its mouth. It stopped to watch her, thought for a moment, stared at her with bitter green eyes, then crept up to where she stood, laid its snout against her knee, sighed deeply, and continued on its way. Farther up the mountain a thick-furred camel swayed, pulling a flimsy long-shafted cart behind it. The man saw the girl. He walked over to her.

âYou can't see farther than your nose, no matter how you try. But remember, even at the darkest moments, beyond the dead horizon, there's always life. When Mishka left, I envied him. He got away and I stayed behind. But now â¦'

He smelled like warm sweat. The strong sunlight reflected from the frozen mountainside where powdered snow had fallen during the night. A light, melancholy feeling floated like a low cloud over the pure landscape. He scratched the back of his head thoughtfully. The sky glowed with spring light.

âDo you know why people live longer than other animals do? It's because animals live by their instincts, and they don't make mistakes. We people, on the other hand, rely on reason, and we screw up all the time. We spend half our lives messing things up, half realising the stupid mistakes we've made, and the rest of the time trying to fix whatever we can. We need all the years we live for all that rigamarole. I was born in 1941. My father, whom I didn't get to choose, begat me on his way from the work camp to the front. My mother is a mean, bitter woman. She hated my father for travelling in a prison carriage to get to a soup kettle in Siberia, leaving her to be trampled by the war and starve. I knew everything about life when I was five, and I spent the next forty years trying to understand it.'

He picked up a handful of rocks and started to toss them into the water. She could see his hands growing hard.

âI often wonder at how I've managed to stay alive. When I was young I was crazy with fear, then I learned to overcome fear. I studied judo and five years later I was a black belt. After that I wasn't afraid. I'm ready to die at any time. I still get goosebumps when I go home to Moscow and hear my mother breathing in the next room. I despise my mother; sometimes I feel sorry for her. A person who's always right is a blind, deaf murderer. But you wouldn't understand that, and you don't have to. As long as you're here.'

He stopped speaking and a smothered silence settled around them. He took his knife out of his boot, sprang its sharp blade open, and felt it with a finger, its brightly polished surface. Disappointment lay deep in his half-closed eyes.

âI didn't have a family, or relationships. That thread broke before I was born, and why wake the ghosts of the past? The cart of the past only leads to the rubbish dump.' He held the knife out to her. âThis is my father's cross, a Siberian knife. I don't know all he did with it, but I stabbed Vimma with this knife. One good-for-nothing killing another.'

He touched his cheek with the blade. âIt's yours now.'

She took the knife. It was heavy. The black handle was made of bone and had a silver Orthodox cross inlaid in it. She felt the power of the knife, and the trip up to this point, with all its light and shadow, flooded through her. Its joys, sorrows, hope, hopelessness, hate and, perhaps, love. Then she looked him in the eye and said, as Job said: âFor the thing which I greatly feared is come upon me, and that which I was afraid of is come to me, Vadim Nikolayevich.'

He touched her hand tenderly, took a pack of

papirosas

out of his pocket, and lit one. She snapped the blade open and looked at the man's hands. She looked at the heavy sharp knife. How many people had been killed with it?

She dug in her pocket, took out a twenty-five-rouble note, and handed it to him. He took the note, smiling faintly, and folded it into his pocket. The thick snow squeaked under his heavy leather shoes. Tatters of large light snowflakes drifted from the sky.

When he left, the children came. They admired and begged for everything she had on: a ring, a necklace, buttons, a belt, hairpins, her scarf. She handed her necklace to the oldest boy. He looked at it for a moment, threw it on the ground, and started to beg for her shoes. Black-tailed squirrels followed after the children. They jumped onto her shoulders and head; one tried to nibble at her face. The children swarmed around her and sicced the squirrels on her. One small boy had a stick in his hand and he tried to poke her with it. When she screamed loudly he dashed away, but he soon came back and continued to poke her. She grabbed the stick from his hand and broke it in two. The boy started to bawl, the squirrels disappeared, and the other children laughed.

She went walking along the shore of the river. The children followed her every step; one of them was throwing small stones at her. The women watched the children and chuckled proudly. The girl put her hand in her pocket and felt the knife; she didn't think about the children or the women.

The sleepy sky darkened quickly and a strong wind from the mountains threw down a brief shower of grainy snow. Then the wind calmed and the peace of a spring night settled over everything.

Dusk hung lightly over the village as the Mongolian man and Gafur returned from the mountain with the flock of sheep. The Mongolian slaughtered one large sheep, let it bleed from the neck into a red plastic bucket, and handed the bucket to the old woman. She disappeared with it into a yurt.

The Mongolian man flayed the sheep and he and Gafur cut up the meat. Meanwhile the women lit a fire on a stove in the yard. When the meat was cut up, the man put the pieces in the bloody sheepskin, and he and Gafur dragged the bundle over to the stove.

The man opened the stove lid. It was full of hot rocks. He picked up a pair of tongs, lifted the stones one by one off the stove, and put them inside the sheepskin. Then he and Gafur hung the whole thing over the fire to burn the wool from the skin.

An hour later they opened the skin and lifted the cooked meat into a metal dish. A cold wind was rising from the northwest.

The girl went into the yurt to warm herself. The man was sitting at a low table, relaxed, twirling a teaspoon in a glass. She rubbed her hands together over the open fire.

âIt'll be May soon, my girl,' he said. âI like April, but I hate May in Siberia. The wind starts to blow from rotten places, and it brings horrible blizzards with it. It feels obscene and disgusting.'

The limp sun melted from the sky and the moon rose. They sat on the floor of the yurt, each of them in their place. The man handed the host a hand auger, marmalade, a jar of pickles, and a pile of newspapers as a gift, and for the hostess some Polish perfume and amber beads. In return he received fifteen fresh marmot skins. They ate the good mutton in the warmth of the yurt and raised their glasses. Gafur filled a water pipe with marijuana grown in Astrahan and some

neftyanka

made from Khazakstani hemp, strong and oily. The men smoked â it wasn't offered to the women.

It was quiet. A young woman poured

kumis

into mugs.

As evening fell, Gafur and the man got up to leave. They made their long goodbyes to the old man and the women, gave out a few more gifts, and finally went outside. She followed them. Gusty winds tossed fine icy snow through the air. There was a turquoise ring around the grey moon.

The travellers got into the car, the men in front, the girl in the back as before. The car started, huffing and banging. A flock of children ran after it, throwing stones.

The whirling snowstorm and dark of early evening gradually aged into night over the ancient mountains, and made the girl's thoughts return to Moscow. She thought about those Moscow mornings when thick fog covered both shores of the Moscow River, how the fresh, ice-cold water trickled through the fog, the metro trains full of people, country people getting their enormous bags stuck in the metro doors, confused by the escalators, pushing and crowding and dashing around, the mass of passengers drifting from one tunnel to the next. She forgot everything else for a moment. A sandstorm from the north lashed lazily at the windshield.

They got back to the city after midnight.

THEY STOOD FOR A MOMENT

in front of the hotel, the two men smoking farewell cigarettes. The man looked at her sharply with his bright eyes, peering from under his brows in the eastern manner, a serious yet boyish look of excitement on his face.

âWe're going out goating, going to get a smell of life and death,' he said, waving a hand faintly at her as he went.

The girl sat in her dark room until morning. She thought about Mitka, about the time they were on their way back from Irina's friend's dacha. They'd sat in a crowded electric train that smelled of want and apathy. She'd leaned against Mitka's shoulder and felt motion, the motion of everything around her and the motion inside her. She'd fallen asleep and Mitka had woken her at Moscow station, asked her to name an eighteen-digit number. She said a number and it took only a moment for him to name its fifth root. He practised logarithms with great enthusiasm, the numbers sometimes growing so large in his head that they gave him a fever.

Not until the east was painted in blue light and the stars yellowed to mandarin behind a veil of clouds did the first tears streak down her cheeks.

The tour guide was waiting for her at the restaurant door at breakfast. They ate in silence. The guide looked at her nonchalantly and suggested that she spend her last day in Ulan Bator on her own â he had a German tourist coming.

All day long, a silent snow fell. A gentle wind swept the snow into the potholes to cover the frozen, muddy water. All that was grey and dull had disappeared. She stepped into a café. Amid the everyday stench and the smell of roasted mutton a primus stove whistled, children wrestled in the slush on the floor, a schoolboy caught the light on the windowsill in a piece of mirror, and she drank a cup of tea with goat's milk.

In the evening she went back to the hotel, packed her few things, put her airline tickets on the bedside table, and focused on breathing. A pleasant gloom searched its way towards her, then reached her. A dim orange star dangling in a crescent moon. The pair of them couldn't quite light up the sleeping town. The stars had fallen frozen into the red sand of the Gobi Desert. Only Venus twinkled in the sky, bright and blazing. The last snowflakes drifted to the ground. She was ready to meet her life, its happiness and unhappiness.

She was ready to go back to Moscow! To Moscow!

THANKS

Riikka Ala-Harja, Jonni Aromaa, Mihail Berg, Jelena Bonner, Vladimir Dudintsev, Viktor Erofeyev, Venedikt Erofeyev, J. K. Ihalainen, Ilf and Petrov, Anne Kaihua, Risto Kautto, Mihail Lermontov, Nikolai Leskov, Sari Lindstén, Jukka Mallinen, Nadežda Mandelstam, Pekka Mustonen, Vladimir Nabokov, Eila Niaska, Teija Oikkonen, Soï¬ Oksanen, Outi Parikka, Konstantin Paustovsky, Viktor Pelevin, Paula Pesonen, Pekka Pesonen, Lyudmila Petrushevskaya, Andrei Platonov, Yevgeni Popov, Nina Sadur, Varlam Salamov, Esa Seppänen, Vasili Shukshin, Konstantin Simonov, Andrei Sinyavsky, Vladimir Sorokin, Marina Tarkovskaya, Andrei Tarkovsky, Tatyana Tolstaya, Leo Tolstoy, Artemi Troitski, Yury Trifonov, Marina Tsvetaeva, Ivan Turgenev, Lyudmila Ulitskaya, Jarmo Valtanen, Galina Vishnevskaya, Marina Vlady, Sergei Yesenin, Mihail Zoshchenko, and many others

WORLD LITERATURE from SERPENT'S TAIL

THE BOOK OF DISQUIET

Fernando Pessoa

âThe very book to read when you wake at 3am and can't get back to sleep â mysteries, misgivings, fears and dreams and wonderment. Like nothing else' Phillip Pullman

ISBN 978 184668 7358

eISBN 978 184765 2379

DOÃA FLOR AND HER TWO HUSBANDS

Jorge Amado

âA master storyteller'

TLS

ISBN 978 185242 7108

THE PASSPORT

Herta Müller

Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature

ISBN 978 185242 1397

eISBN 978 184765 2492

THE PIANO TEACHER

Elfriede Jelinek

Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, and a major film by Michael Haneke

ISBN 978 184668 7372

eISBN 978 184765 3062

HER PRIVATES WE

Frederic Manning

â[I read

Her Privates We

] every year to remember how things really were so that I will never lie to myself or anyone else about them' Ernest Hemingway

ISBN 978 184668 7877

eISBN 978 184765 7640

NO MAN'S LAND

Edited by Pete Ayrton

The first international collection of First World War fiction by contemporary writers

ISBN 978 184668 9253

eISBN 978 184765 9224

TOMORROW I'LL BE TWENTY

Alain Mabanckou

âIrreverent wit and madcap energy' Giles Foden, author of

The Last King of Scotland

ISBN 978 184668 5842

eISBN 978 184765 7893

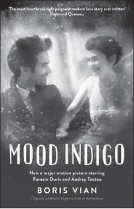

MOOD INDIGO

Boris Vian

French cult classic is now a film by Michel Gondry

ISBN 978 184668 9444

eISBN 978 184765 9699