Complete History of Jack the Ripper (56 page)

Read Complete History of Jack the Ripper Online

Authors: Philip Sudgen

Presumably the man in the building trade was Joe Flemming, the plasterer also mentioned by Barnett. It is obvious that an especially close relationship once existed between Mary and Flemming. Barnett tells us that Mary was very fond of him. Mrs Carthy believed that Flemming would have married Mary. And Mary told Julia Venturney, a German charwoman who lodged opposite her in Miller’s Court, that a man called Joe continued to visit her after she had taken up with Barnett. But we know next to nothing about this or any other of Mary’s early relationships. Our sources, too, leave important questions unanswered. Why did Mary leave Wales for London? What was the truth behind the stories of the West End brothel and that mysterious jaunt to France? And why was a girl of Mary’s youth and apparent good looks precipated so swiftly into the desperate squalor of the East End lodging house? Ripperologists have pondered such questions for decades. We can reap a harvest of speculation and theory from their labours. But they are no substitute for facts.

Mary’s life acquires sharper focus after her meeting with Joe Barnett in Commercial Street in 1887. At that time she was living at Cooley’s lodging house in Thrawl Street.

4

Barnett, a steady respectable Irish cockney, worked as a market porter at Billingsgate. The two struck up an immediate friendship. Over a drink they arranged to meet again the next day and on that second meeting agreed to live together. At first the couple took lodgings in George Street. From there they moved to Little Paternoster Row, Dorset Street, and from there, evicted for getting drunk and failing to pay their rent, to Brick Lane. At the beginning of 1888 they rented 13 Miller’s Court from John McCarthy, the owner of a chandler’s shop at 27 Dorset Street.

Neither the horrendous scene-of-crime photographs taken by the police nor the fanciful sketches of the illustrated papers help us to visualize Mary’s appearance. But she was young and evidently quite

attractive. Mrs Phoenix said that she was about ‘5 feet 7 inches in height, and of rather stout build, with blue eyes and a very fine head of hair, which reached nearly to her waist.’ Some of Mary’s neighbours in Dorset Street have also left us word portraits of her. To Elizabeth Prater, lodging in a room directly over Mary’s, she was ‘tall and pretty, and as fair as a lily’, a very pleasant girl who ‘seemed to be on good terms with everybody’. To Caroline Maxwell, living in Dorset Street across the way from Miller’s Court, ‘a pleasant little woman, rather stout, fair complexion, and rather pale . . . she spoke with a kind of impediment.’

5

The only durable result of her French connection seems to have been the affectation of the name Marie Jeanette Kelly.

Mary lived at Miller’s Court with Joe Barnett until 30 October, when Barnett walked out after a quarrel. He had been out of work for several months, the couple had fallen behind in their rent and Mary had returned to prostitution. Her trade had occasioned differences between the two. ‘I have heard him say that he did not like her going out on the streets,’ Julia Venturney, a neighbour, told the police, ‘he frequently gave her money, he was very kind to her, he said he would not live with her while she led that course of life.’

6

But Mary’s compassion was the immediate cause of their separation. Always big-hearted, she invited a homeless prostitute to share their room at Miller’s Court.

7

Barnett suffered the intrusion two or three nights and then remonstrated and left.

Barnett found shelter in. a common lodging house in New Street, Bishopsgate, but he and Mary remained friends. On the evening of Thursday, 8 November, he visited her at Miller’s Court and told her that he was very sorry he had no work and could not give her any money. The terror that had gripped the East End that autumn had touched Mary as it had every other prostitute. In Dorset Street, within a few yards of the entrance to Miller’s Court, a bill proclaiming the

Illustrated Police News

£100 reward offer hung precariously from a wall. And several times Mary had asked Barnett to read to her from the newspapers about the murders. But when they parted that Thursday night, perhaps about eight, neither could possibly have anticipated the disaster that was about to engulf them. It was the last time Barnett saw Mary alive. And when he would look upon her, dead and mangled in Shoreditch Mortuary, he would recognize her only by her hair and eyes.

8

Friday, 9 November 1888. The day of the Lord Mayor’s Show. The day when the Right Honourable James Whitehead, the new Lord

Mayor, would drive in state, amidst all the pomp and pageantry the wealthiest city in the kingdom could devise, to the Royal Courts of Justice in the Strand for his oath of office. Mary would have enjoyed the festivities. Apparently she had been looking forward to it. ‘I hope it will be a fine day tomorrow,’ she had told Mrs Prater on Thursday morning, ‘as I want to go to the Lord Mayor’s Show.’

9

John McCarthy, Mary’s landlord, had other things on his mind. At 10.45 on Friday morning he was in his shop at 27 Dorset Street and checking his books with concern. He was not a hard man but he had already allowed Mary to clock up 29s. in rent arrears. So, calling Thomas Bowyer, his shop assistant, he sent him round to her room to see if she could pay the money. Perhaps he thought they might catch her before she disappeared to see the Lord Mayor’s procession.

10

Bowyer knocked twice at the door of No. 13. Each time there was no answer. He stepped round the corner to the broken window and, reaching inside, pulled aside the curtain. A first glance into the room revealed two lumps of flesh on the bedside table. A second discovered Mary’s bloody and mutilated corpse lying on the bed itself. It was enough for poor Bowyer. He fled precipitately back to the shop. ‘Governor,’ he stammered, ‘I knocked at the door and could not make anyone answer. I looked through the window and saw a lot of blood.’ Such words, in the East End that autumn, presaged horrific murder, and filled with forebodings McCarthy returned with Bowyer to No. 13. There the sight which greeted the landlord when he looked through the window was even more stomach-turning than he had prepared himself for. The bedside table was covered with what looked like pieces of flesh and the body on the bed resembled that of a butchered beast. White-faced and shaken, he turned to Bowyer. ‘Go at once to the police station,’ he said, ‘and fetch someone here.’

At Commercial Street Bowyer found Inspector Walter Beck on duty. Chatting with him was Walter Dew, the young detective who, fifty years later, recalled for us Bowyer’s dramatic entrance. A youth, his eyes bulging out of his head, burst panting into the station. For a time he was so overcome with fright as to be unable to utter a single intelligible word. But at last he managed to babble something: ‘Another one. Jack the Ripper. Awful. Jack McCarthy sent me.’

11

Soon they were hearing the tale from McCarthy himself who, having recovered his composure, had hurried after his assistant. ‘Come along, Dew,’ said the inspector, donning his hat and coat, and they set out together with Bowyer and McCarthy for the scene of the crime. They arrived at Miller’s Court at or soon after eleven. ‘The room was pointed out to me,’ recalled Dew. ‘I tried the door. It would not yield. So I moved to the window, over which, on the inside, an old coat was hanging to act as a curtain and to block the draught from the hole in the glass. Inspector Beck pushed the coat to one side and peered through the aperture. A moment later he staggered back with

his face as white as a sheet. ‘For God’s sake, Dew,’ he cried. ‘Don’t look.’ I ignored the order, and took my place at the window. When my eyes had become accustomed to the dim light I saw a sight which I shall never forget to my dying day.’

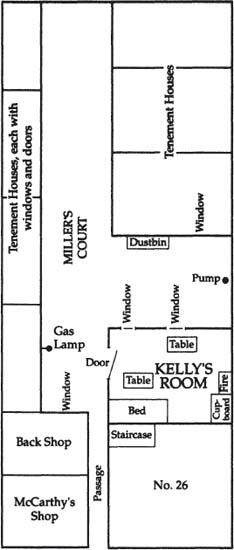

DORSET STREET

Miller’s Court and Mary Jane Kelly’s room

Miller’s Court was soon bustling with police personnel. Dr George Bagster Phillips, the divisional police surgeon, arrived at 11.15. Abberline was there by 11.30. Both must share some responsibility for the ensuing fiasco. The door of Mary’s room was locked but, incredibly, no attempt was made to force it until 1.30 in the afternoon. Although Phillips was primarily responsible for the delay the testimony he gave three days later at the inquest cannot be said to be very illuminating on the point. There he described how, having looked through the broken window and ascertained that Mary was beyond help, he decided that ‘probably it was advisable that no entrance should be made into the room at that time.’ It was left to Abberline, who had charge of the case, to explain this bizarre decision to the inquest: ‘I had an intimation from Inspector Beck that the dogs had been sent for [and] Dr Phillips asked me not to force the door but to test the dogs if they were coming.’

12

The dogs, as we now know, were no longer available, and in the two and a half hours after eleven the police did little more than seal off Miller’s Court, accumulate statements from local residents and get in a photographer to photograph the corpse. At 1.30 Superintendent Arnold arrived. He brought the news that the order for the bloodhounds had been countermanded and gave immediate instructions for the door to be forced. John McCarthy then broke it open with a pickaxe. It was an unfortunate beginning to the investigation. Even the violence visited upon the offending door was unnecessary. Joe Barnett later told Abberline that the key had been missing for some time. The door had a spring lock that fastened automatically when it was pulled to but the catch could easily be moved back from the outside by reaching through the broken window!

The little room was cluttered. As the door was pushed open it banged against the bedside table. A moment later Abberline and his team were inside. The sight that met their eyes was one to haunt dreams.

Sparsely furnished, the room was nevertheless so small that there was very little space in which to move around. It was about twelve or fifteen feet square. The bedside table, against which the door had knocked, was close to the left-hand side of an ancient wooden

bedstead and the right-hand side of the bedstead was close up against the wooden partition which sealed Mary’s room off from the rest of the house. The only other furnishings were another old table, a chair or two, a cupboard, a disused washstand and a fireplace. The grate contained the ashes of a large fire. There was little attempt at decoration. A cheap print, ‘The Fisherman’s Widow’, hung over the fireplace. But the floorboards were bare and filthy and although the walls themselves were papered the pattern was barely discernible beneath the dirt.

Mary’s body, grotesquely mutilated, lay on the bed, two-thirds over towards the left-hand edge, that nearest the door. The first person through the door was Dr Phillips. From Phillips, above all others, we might have expected an authentic report about the condition of the body but he tells us almost nothing. Certainly he spoke at the inquest three days later. On that occasion, however, he deliberately suppressed the details of Mary’s injuries. The immediate cause of death, he said, was the severance of the right carotid artery. From the blood-saturated condition of the palliasse, pillow and sheet at the top right-hand corner of the bed, and from the large quantity of blood found under the bedstead there, he deduced that she had been moved from the right-hand side of the bed after receiving her death wound.

13

Phillips’ silence ensured that for a century little authentic scene-of-crime information was known about what was perhaps the Ripper’s last and most gruesome murder. Then, in 1987, a set of long-lost medical notes made by Dr Thomas Bond, who had worked with Phillips at Miller’s Court and during the subsequent post-mortem, came to light among a bundle of documents posted anonymously to Scotland Yard. These notes, written on 10 November 1888, after the post-mortem, blow to bits the untrustworthy news reports and the fictional flourishes of Ripperologists that have served to bridge the gap in the documentation for so many years.

Dr Bond had been sucked into the Ripper investigation as early as 25 October, when Anderson had written to him requesting him to review the medical evidence given at the inquests and to hazard an opinion respecting the killer’s alleged anatomical knowledge. ‘In dealing with the Whitechapel murders,’ the Assistant Commissioner had explained, ‘the difficulties of conducting the inquiry are largely increased by reason of our having no reliable opinion for our guidance as to the amount of surgical skill and anatomical knowledge probably

possessed by the murderer or murderers.’

14

Anderson looked to Bond for such guidance and, on the face of it, there were few more qualified to give it. For in addition to conducting the post-mortem examination in the celebrated Whitehall torso case at the beginning of October

15

he had twenty-one years’ experience as police surgeon to A Division.