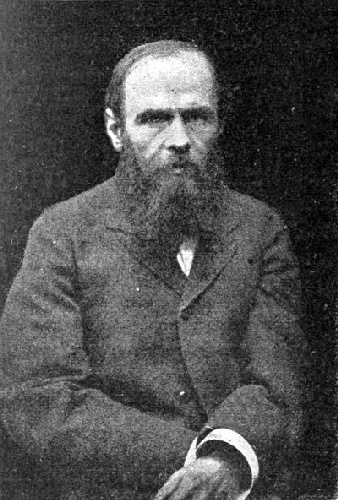

Complete Works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky (446 page)

Read Complete Works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky Online

Authors: Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Velchaninoff returned home and opened the letter, which was sealed and addressed to himself.

There was not a syllable inside in Pavel Pavlovitch’s own hand writing; but he drew out another letter, and knew the writing at once. It was an old, faded, yellow-looking sheet of paper, and the ink was faint and discoloured; the letter was addressed to Velchaninoff, and written ten years before — a couple of months after his departure from T —— . He had never received a copy of this one, but another letter, which he well remembered, had evidently been written and sent instead of it; he could tell that by the substance of the faded document in his hand. In this present letter Natalia Vasilievna bade farewell to him for ever (as she had done in the other communication), and informed him that she expected her confinement in a few months. She added, for his consolation, that she would find an opportunity of purveying his child to him in good time, and pointed out that their friendship was now cemented for ever. She begged him to love her no longer, because she could no longer return his love, but authorized him to pay a visit to T —— after a year’s absence, in order to see the child. Goodness only knows why she had not sent this letter, but had changed it for another!

Velchaninoff was deadly pale when he read this document; but he imagined Pavel Pavlovitch finding it in the family box of black wood with mother-of-pearl ornamentation and silver mounting, and reading it for the first time!

“I should think he, too, grew as pale as a corpse,” he reflected, catching sight of his own face in the looking-glass. “Perhaps he read it and then closed his eyes and hoped and prayed that when he opened them again the dreadful letter would be nothing but a sheet of white paper once more! Perhaps the poor fellow tried this desperate expedient two or three times before he accepted the truth!”

CHAPTER XVII.

Two years have elapsed since the events recorded in the foregoing chapters, and we find our friend Velchaninoff, one lovely summer day, seated in a railway carriage on his way to Odessa; he was making the journey for the purpose of seeing a great friend, and of being introduced to a lady whose acquaintance he had long wished to make.

Without entering into any details, we may remark that Velchaninoff was entirely changed during these last two years. He was no longer the miserable, fanciful hypochondriac of those dark days. He had returned to society and to his friends, who gladly forgave him his temporary relapse into seclusion. Even those whom he had ceased to bow to, when met, were now among the first to extend the hand of friendship once more, and asked no questions — just as though he had been abroad on private business, which was no affair of theirs.

His success in the legal matters of which we have heard, and the fact of having his sixty thousand roubles safe at his bankers — enough to keep him all his life — was the elixir which brought him back to health and spirits. His premature wrinkles departed, his eyes grew brighter, and his complexion better; he became more active and vigorous — in fact, as he sat thinking in a comfortable first-class carriage, he looked a very different man from the Velchaninoff of two years ago.

The next station to be reached was that at which passengers were expected to dine, forty minutes being allowed for this purpose.

It so happened that Velchaninoff, while seated at the dinner table, was able to do a service to a lady who was also dining there. This lady was young and nice looking, though rather too flashily dressed, and was accompanied by a young officer who unfortunately was scarcely in a befitting condition for ladies’ society, having refreshed himself at the bar to an unnecessary extent. This young man succeeded in quarrelling with another person equally unfit for ladies’ society, and a brawl ensued, which threatened to land both parties upon the table in close proximity to the lady. Velchaninoff interfered, and removed the brawlers to a safe distance, to the great and almost boundless gratitude of the alarmed lady, who hailed him as her “guardian angel.” Velchaninoff was interested in the young woman, who looked like a respectable provincial lady — of provincial manners and taste, as her dress and gestures showed.

A conversation was opened, and the lady immediately commenced to lament that her husband was “never by when he was wanted,” and that he had now gone and hidden himself somewhere just because he happened to be required.

“Poor fellow, he’ll catch it for this,” thought Velchaninoff. “If you will tell me your husband’s name,” he added aloud, “I will find him, with pleasure.”

“Pavel Pavlovitch,” hiccupped the young officer.

“Your husband’s name is Pavel Pavlovitch, is it?” inquired Velchaninoff with curiosity, and at the same moment a familiar bald head was interposed between the lady and himself.

“Here you are

at last

,” cried the wife, hysterically.

It was indeed Pavel Pavlovitch.

He gazed in amazement and dread at Velchaninoff, falling back before him just as though he saw a ghost. So great was his consternation, that for some time it was clear that he did not understand a single word of what his wife was telling him — which was that Velchaninoff had acted as her guardian angel, and that he (Pavel) ought to be ashamed of himself for never being at hand when he was wanted.

At last Pavel Pavlovitch shuddered, and woke up to consciousness.

Velchaninoff suddenly burst out laughing. “Why, we are old friends” — he cried, “friends from childhood!” He clapped his hand familiarly and encouragingly on Pavel’s shoulder. Pavel smiled wanly. “Hasn’t he ever spoken to you of Velchaninoff?”

“No, never,” said the wife, a little confused.

“Then introduce me to your wife, you faithless friend!”

“This — this is Mr. Velchaninoff!” muttered Pavel Pavlovitch, looking the picture of confusion.

All went swimmingly after this. Pavel Pavlovitch was despatched to cater for the party, while his lady informed Velchaninoff that they were on their way from O —— , where Pavel Pavlovitch served, to their country place — a lovely house, she said, some twenty-five miles away. There they hoped to receive a party of friends, and if Mr. Velchaninoff would be so very kind as to take pity on their rustic home, and honour it with a visit, she should do her best to show her gratitude to the guardian angel who, etc., etc. Velchaninoff replied that he would be delighted; and that he was an idle man, and always free — adding a compliment or two which caused the fair lady to blush with delight, and to tell Pavel Pavlovitch, who now returned from his quest, that Alexey Ivanovitch had been so kind as to promise to pay them a visit next week, and stay a whole month.

Pavel Pavlovitch, to the amazed wrath of his wife, smiled a sickly smile, and said nothing.

After dinner the party bade farewell to Velchaninoff, and returned to their carriage, while the latter walked up and down the platform smoking his cigar; he knew that Pavel Pavlovitch would return to talk to him.

So it turned out. Pavel came up with an expression of the most anxious and harassed misery. Velchaninoff smiled, took his arm, led him to a seat, and sat down beside him. He did not say anything, for he was anxious that Pavel should make the first move.

“So you are coming to us?” murmured the latter at last, plunging

in medias res

.

“I knew you’d begin like that! you haven’t changed an atom!” cried Velchaninoff, roaring with laughter, and slapping him confidentially on the back. “Surely, you don’t really suppose that I ever had the smallest intention of visiting you — and staying a month too!”

Pavel Pavlovitch gave a start.

“Then you’re

not

coming?” he cried, without an attempt to hide his joy.

“No, no! of course not!” replied Velchaninoff, laughing. He did not know why, but all this was exquisitely droll to him; and the further it went the funnier it seemed.

“Really — are you really serious?” cried Pavel, jumping up.

“Yes; I tell you, I won’t come — not for the world!”

“But what will my wife say now? She thinks you intend to come!”

“Oh, tell her I’ve broken my leg — or anything you like!”

“She won’t believe!” said Pavel, looking anxious.

“Ha-ha-ha! You catch it at home, I see! Tell me, who is that young officer?”

“Oh, a distant relative of mine — an unfortunate young fellow — —”

“Pavel Pavlovitch!” cried a voice from the carriage, “the second bell has rung!”

Pavel was about to move off — Velchaninoff stopped him.

“Shall I go and tell your wife how you tried to cut my throat?” he said.

“What are you thinking of — God forbid!” cried Pavel, in a terrible fright.

“Well, go along, then!” said the other, loosing his hold of Pavel’s shoulder.

“Then — then — you won’t come, will you?” said Pavel once more, timidly and despairingly, and clasping his hands in entreaty.

“No — I won’t — I swear! — run away — you’ll be late!” He put out his hand mechanically, then recollected himself, and shuddered. Pavel did not take the proffered hand, he withdrew his own.

The third bell rang.

An instantaneous but total change seemed to have come over both. Something snapped within Velchaninoff’s heart — so it seemed to him, and he who had been roaring with laughter a moment before, seized Pavel Pavlovitch angrily by the shoulder.

“If I —

I

offer you my hand, sir” (he showed the scar on the palm of his left hand)— “if

I

can offer you my hand, sir, I should think

you

might accept it!” he hissed with white and trembling lips.

Pavel Pavlovitch grew deadly white also, his lips quivered and a convulsion seemed to run through his features:

“And — Liza?” he whispered quickly. Suddenly his whole face worked, and tears started to his eyes.

Velchaninoff stood like a log before him.

“Pavel Pavlovitch! Pavel Pavlovitch!” shrieked the voice from the carriage, in despairing accents, as though some one were being murdered.

Pavel roused himself and started to run. At that moment the engine whistled, and the train moved off. Pavel Pavlovitch just managed to cling on, and so climb into his carriage, as it moved out of the station.

Velchaninoff waited for another train, and then continued his journey to Odessa.

THE END

OR, DEVILS; OR, DEMONS

Translated by Constance Garnett

The Possessed

was first published in 1872 and is a deeply political novel, providing a vivid testimonial of life in Imperial Russia in the late 19th century. The novel presents five primary characters, each epitomising different ideologies. By exploring their differing philosophies, Dostoyevsky describes the political chaos seen in his contemporary Russia.

The original Russian title uses the Russian word ‘Бесы’, which means "demons", conveying the idea of the gradual collapse of the Russian Orthodox Church, bringing about the imperceptible spread of bésy, "little beasts" or "demons", symbolising the oncoming nihilistic concepts of the first half of the 20th century.

The novel takes place in a provincial Russian setting, primarily on the estates of Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky and Varvara Stavrogina. Stepan Trofimovich's son, Pyotr Verkhovensky, is an aspiring revolutionary conspirator, attempting to organise a band of revolutionaries in the area. He considers Varvara Stavrogina's son, Nikolai, central to his plot because he thinks Nikolai Stavrogin has no sympathy for mankind whatsoever. Verkhovensky gathers conspirators like the philosophising Shigalyov, suicidal Kirillov and the former military figure Virginsky, and he schemes to solidify their loyalty to him and each other by murdering Ivan Shatov, a fellow conspirator. Verkhovensky plans to have Kirillov, who was committed to killing himself, take credit for the murder in his suicide note. Kirillov complies and Verkhovensky murders Shatov, but his scheme begins to falls apart.

Interestingly,

The Possessed

is a combination of two separate works that Dostoyevsky was working upon at the same time. One narrative was a commentary on the real-life murder in 1869 by the socialist revolutionary group (People's Vengeance) of one of its own members (Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov). The character Pyotr Verkhovensky is based upon the leader of this revolutionary group, Sergey Nechayev, who was found guilty of this murder. Sergey Nechayev was a close confidant of Mikhail Bakunin, who had direct influence over both Nechayev and the "People's Vengeance". The character Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky is based upon Timofey Granovsky. The other novel eventually melded into

The Possessed

was originally a religious work. The most immoral character Stavrogin was to be the hero of this novel and is now commonly viewed as the most important character in the novel.