Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen (227 page)

Read Complete Works of Henrik Ibsen Online

Authors: Henrik Ibsen

Mrs. Stockmann. Yes, if only we could live on sunshine and spring air, Thomas.

Dr. Stockmann. Oh, you will have to pinch and save a bit — then we shall get along. That gives me very little concern. What is much worse is, that I know of no one who is liberal-minded and high-minded enough to venture to take up my work after me.

Petra. Don’t think about that, father; you have plenty of time before you. — Hello, here are the boys already!

(EJLIF and MORTEN come in from the sitting-room.)

Mrs. Stockmann. Have you got a holiday?

Morten. No; but we were fighting with the other boys between lessons —

Ejlif. That isn’t true; it was the other boys were fighting with us.

Morten. Well, and then Mr. Rorlund said we had better stay at home for a day or two.

Dr. Stockmann

(snapping his fingers and getting up from the table)

. I have it! I have it, by Jove! You shall never set foot in the school again!

The Boys. No more school!

Mrs. Stockmann. But, Thomas —

Dr. Stockmann. Never, I say. I will educate you myself; that is to say, you shan’t learn a blessed thing —

Morten. Hooray!

Dr. Stockmann. — but I will make liberal-minded and high-minded men of you. You must help me with that, Petra.

Petra, Yes, father, you may be sure I will.

Dr. Stockmann. And my school shall be in the room where they insulted me and called me an enemy of the people. But we are too few as we are; I must have at least twelve boys to begin with.

Mrs. Stockmann. You will certainly never get them in this town.

Dr. Stockmann. We shall.

(To the boys.)

Don’t you know any street urchins — regular ragamuffins — ?

Morten. Yes, father, I know lots!

Dr. Stockmann. That’s capital! Bring me some specimens of them. I am going to experiment with curs, just for once; there may be some exceptional heads among them.

Morten. And what are we going to do, when you have made liberal-minded and high-minded men of us?

Dr. Stockmann. Then you shall drive all the wolves out of the country, my boys!

(EJLIF looks rather doubtful about it; MORTEN jumps about crying “Hurrah!”)

Mrs. Stockmann. Let us hope it won’t be the wolves that will drive you out of the country, Thomas.

Dr. Stockmann. Are you out of your mind, Katherine? Drive me out! Now — when I am the strongest man in the town!

Mrs. Stockmann. The strongest — now?

Dr. Stockmann. Yes, and I will go so far as to say that now I am the strongest man in the whole world.

Morten. I say!

Dr. Stockmann

(lowering his voice)

. Hush! You mustn’t say anything about it yet; but I have made a great discovery.

Mrs. Stockmann. Another one?

Dr. Stockmann. Yes.

(Gathers them round him, and says confidentially:)

It is this, let me tell you — that the strongest man in the world is he who stands most alone.

Mrs. Stockmann

(smiling and shaking her head)

. Oh, Thomas, Thomas!

Petra

(encouragingly, as she grasps her father’s hands)

. Father!

CK

Translated by William Archer

Ibsen began working on this play in 1884 and in one of his notes at the time he writes, “The metaphor of the wild duck: when they are wounded they sink straight to the bottom, the stubborn devils, and hold on with their beaks”. This metaphor was inspired by Welhaven’s poem

The Sea Bird

. On April 20, 1884 Ibsen started on the first act, taking eight days, whilst the second act was started on May 2nd, but broken off midway. The first and second acts were then rewritten up to May 24th. The third and fourth acts were written in the period between May 25th and June 8th, while the fifth act was done between the 9th and 13th of June. The following day Ibsen wrote to his Danish publisher Frederik Hegel: “This play does not deal with political or social or public issues at all. It has entirely to do with family life. It will doubtless cause some discussion, but it will not offend anyone.”

At the end of June, Ibsen left Rome for Gossensass, where he spent the next four months mostly alone, while Suzannah and Sigurd were staying in Norway. He started the work of writing the fair copy several times, but it wasn’t until September the final version was ready and Ibsen sent the fair copy of the manuscript to Hegel.

The Wild Duck

was published on November 11, 1884 at Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag in Copenhagen and Christiania in an edition of 8,000 copies. Both reviewers and readers were somewhat puzzled by the play, compared to the previous two ‘bombshell’ works.

The Wild Duck

introduces what has since become known as the symbolic phase in Ibsen’s writing and it is the use of symbols in the play that seemed strange and confusing to its first readers.

The play had its first performance on January 9, 1885 at Den nationale Scene in Bergen. The production was a success, largely owing to its director, Gunnar Heiberg. Two days later the play had its first night at Christiania Theatre and was received well.

The first act opens with a dinner party hosted by Håkon Werle, a wealthy merchant and industrialist. The gathering is attended by his son, Gregers Werle, who has just returned to his father’s home following a self-imposed exile. There, he learns the fate of a former classmate, Hjalmar Ekdal. Hjalmar married Gina, a young servant in the Werle household. The elder Werle had arranged the match by providing Hjalmar with a home and profession as a photographer. Gregers, whose mother died believing that Gina and her husband had carried on an affair, becomes enraged at the thought that his old friend is living a life built on a lie.

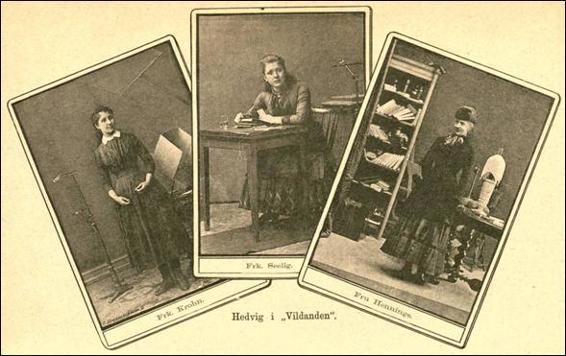

The three Scandanavian actresses that played the role of Hedvig in 1889

WERLE, a merchant, manufacturer, etc.

GREGERS WERLE, his son.

OLD EKDAL.

HIALMAR EKDAL, his son, a photographer.

GINA EKDAL, Hjalmar’s wife.

HEDVIG, their daughter, a girl of fourteen.

MRS. SORBY, Werle’s housekeeper.

RELLING, a doctor.

MOLVIK, student of theology.

GRABERG, Werle’s bookkeeper.

PETTERSEN, Werle’s servant.

JENSEN, a hired waiter.

A FLABBY GENTLEMAN.

A THIN-HAIRED GENTLEMAN.

A SHORT-SIGHTED GENTLEMAN.

SIX OTHER GENTLEMEN, guests at Werle’s dinner-party.

SEVERAL HIRED WAITERS.

The first act passes in WERLE’S house, the remaining acts at HJALMAR EKDAL’S.

[At WERLE’S house. A richly and comfortably furnished study; bookcases and upholstered furniture; a writing-table, with papers and documents, in the centre of the room; lighted lamps with green shades, giving a subdued light. At the back, open folding-doors with curtains drawn back. Within is seen a large and handsome room, brilliantly lighted with lamps and branching candle-sticks. In front, on the right (in the study), a small baize door leads into WERLE’S Office. On the left, in front, a fireplace with a glowing coal fire, and farther back a double door leading into the dining-room.]

[WERLE’S servant, PETTERSEN, in livery, and JENSEN, the hired waiter, in black, are putting the study in order. In the large room, two or three other hired waiters are moving about, arranging things and lighting more candles. From the dining-room, the hum of conversation and laughter of many voices are heard; a glass is tapped with a knife; silence follows, and a toast is proposed; shouts of “Bravo!” and then again a buzz of conversation.]

PETTERSEN.

[lights a lamp on the chimney-place and places a shade over it.]

Hark to them, Jensen! now the old man’s on his legs holding a long palaver about Mrs. Sorby.

JENSEN

[pushing forward an arm-chair.]

Is it true, what folks say, that they’re — very good friends, eh?

PETTERSEN.

Lord knows.

JENSEN.

I’ve heard tell as he’s been a lively customer in his day.

PETTERSEN.

May be.

JENSEN.

And he’s giving this spread in honour of his son, they say.

PETTERSEN.

Yes. His son came home yesterday.

JENSEN.

This is the first time I ever heard as Mr. Werle had a son.

PETTERSEN.

Oh yes, he has a son, right enough. But he’s a fixture, as you might say, up at the Hoidal works. He’s never once come to town all the years I’ve been in service here.

A WAITER

[in the doorway of the other room.]

Pettersen, here’s an old fellow wanting —

PETTERSEN

[mutters.]

The devil — who’s this now?

[OLD EKDAL appears from the right, in the inner room. He is dressed in a threadbare overcoat with a high collar; he wears woollen mittens, and carries in his hand a stick and a fur cap. Under his arm, a brown paper parcel. Dirty red-brown wig and small grey moustache.]

PETTERSEN

[goes towards him.]

Good Lord — what do you want here?

EKDAL

[in the doorway.]

Must get into the office, Pettersen.

PETTERSEN.

The office was closed an hour ago, and —

EKDAL.

So they told me at the front door. But Graberg’s in there still. Let me slip in this way, Pettersen; there’s a good fellow.

[Points towards the baize door.]

It’s not the first time I’ve come this way.

PETTERSEN.

Well, you may pass.

[Opens the door.]

But mind you go out again the proper way, for we’ve got company.

EKDAL.

I know, I know — h’m! Thanks, Pettersen, good old friend! Thanks!

[Mutters softly.]

Ass!

[He goes into the Office; PETTERSEN shuts the door after him.]

JENSEN.

Is he one of the office people?

PETTERSEN.

No he’s only an outside hand that does odd jobs of copying. But he’s been a tip-topper in his day, has old Ekdal.

JENSEN.

You can see he’s been through a lot.

PETTERSEN.

Yes; he was an army officer, you know.

JENSEN.

You don’t say so?

PETTERSEN.

No mistake about it. But then he went into the timber trade or something of the sort. They say he once played Mr. Werle a very nasty trick. They were partners in the Hoidal works at the time. Oh, I know old Ekdal well, I do. Many a nip of bitters and bottle of ale we two have drunk at Madam Eriksen’s.

JENSEN.

He don’t look as if held much to stand treat with.

PETTERSEN.

Why, bless you, Jensen, it’s me that stands treat. I always think there’s no harm in being a bit civil to folks that have seen better days.

JENSEN.

Did he go bankrupt then?

PETTERSEN.

Worse than that. He went to prison.

JENSEN.

To prison!

PETTERSEN.

Or perhaps it was the Penitentiary.

[Listens.]

Sh! They’re leaving the table.

[The dining-room door is thrown open from within, by a couple of waiters. MRS. SORBY comes out conversing with two gentlemen. Gradually the whole company follows, amongst them WERLE. Last come HIALMAR EKDAL and GREGERS WERLE.]

MRS. SORBY

[in passing, to the servant.]

Tell them to serve the coffee in the music-room, Pettersen.

PETTERSEN.

Very well, Madam.

[She goes with the two Gentlemen into the inner room, and thence out to the right. PETTERSEN and JENSEN go out the same way.]

A FLABBY GENTLEMAN

[to a THIN-HAIRED GENTLEMAN.]

Whew! What a dinner! — It was no joke to do it justice!

THE THIN-HAIRED GENTLEMAN.

Oh, with a little good-will one can get through a lot in three hours.

THE FLABBY GENTLEMAN.

Yes, but afterwards, afterwards, my dear Chamberlain!

A THIRD GENTLEMAN.

I hear the coffee and maraschino are to be served in the music-room.

THE FLABBY GENTLEMAN.

Bravo! Then perhaps Mrs. Sorby will play us something.

THE THIN-HAIRED GENTLEMAN

[in a low voice.]

I hope Mrs. Sorby mayn’t play us a tune we don’t like, one of these days!

THE FLABBY GENTLEMAN.

Oh no, not she! Bertha will never turn against her old friends.

[They laugh and pass into the inner room.]

WERLE

[in a low voice, dejectedly.]

I don’t think anybody noticed it, Gregers.

GREGERS

[looks at him.]

Noticed what?

WERLE.

Did you not notice it either?

GREGERS.

What do you mean?

WERLE.

We were thirteen at table.

GREGERS.

Indeed? Were there thirteen of us?

WERLE

[glances towards HIALMAR EKDAL.]

Our usual party is twelve.

[To the others.]

This way, gentlemen!

[WERLE and the others, all except HIALMAR and GREGERS, go out by the back, to the right.]

HIALMAR

[who has overheard the conversation.]

You ought not to have invited me, Gregers.

GREGERS.

What! Not ask my best and only friend to a party supposed to be in my honour — ?

HIALMAR.

But I don’t think your father likes it. You see I am quite outside his circle.

GREGERS.

So I hear. But I wanted to see you and have a talk with you, and I certainly shan’t be staying long. — Ah, we two old schoolfellows have drifted far apart from each other. It must be sixteen or seventeen years since we met.

HIALMAR.

Is it so long?

GREGERS.

It is indeed. Well, how goes it with you? You look well. You have put on flesh, and grown almost stout.

HIALMAR.

Well, “stout” is scarcely the word; but I daresay I look a little more of a man than I used to.

GREGERS.

Yes, you do; your outer man is in first-rate condition.

HIALMAR

[in a tone of gloom.]

Ah, but the inner man! That is a very different matter, I can tell you! Of course you know of the terrible catastrophe that has befallen me and mine since last we met.

GREGERS

[more softly.]

How are things going with your father now?

HIALMAR.

Don’t let us talk of it, old fellow. Of course my poor unhappy father lives with me. He hasn’t another soul in the world to care for him. But you can understand that this is a miserable subject for me. — Tell me, rather, how you have been getting on up at the works.

GREGERS.

I have had a delightfully lonely time of it — plenty of leisure to think and think about things. Come over here; we may as well make ourselves comfortable.

[He seats himself in an arm-chair by the fire and draws HIALMAR down into another alongside of it.]

HIALMAR

[sentimentally.]

After all, Gregers, I thank you for inviting me to your father’s table; for I take it as a sign that you have got over your feeling against me.

GREGERS

[surprised.]

How could you imagine I had any feeling against you?

HIALMAR.

You had at first, you know.

GREGERS.

How at first?

HIALMAR.

After the great misfortune. It was natural enough that you should. Your father was within an ace of being drawn into that — well, that terrible business.

GREGERS.

Why should that give me any feeling against you? Who can have put that into your head?

HIALMAR.

I know it did, Gregers; your father told me so himself.

GREGERS

[starts.]

My father! Oh indeed. H’m. — Was that why you never let me hear from you? — not a single word.

HIALMAR.

Yes.

GREGERS.

Not even when you made up your mind to become a photographer?

HIALMAR.

Your father said I had better not write to you at all, about anything.

GREGERS

[looking straight before him.]

Well well, perhaps he was right. — But tell me now, Hialmar: are you pretty well satisfied with your present position?

HIALMAR

[with a little sigh.]

Oh yes, I am; I have really no cause to complain. At first, as you may guess, I felt it a little strange. It was such a totally new state of things for me. But of course my whole circumstances were totally changed. Father’s utter, irretrievable ruin, — the shame and disgrace of it, Gregers

GREGERS

[affected.]

Yes, yes; I understand.

HIALMAR.

I couldn’t think of remaining at college; there wasn’t a shilling to spare; on the contrary, there were debts — mainly to your father I believe —

GREGERS.

H’m — -

HIALMAR.

In short, I thought it best to break, once for all, with my old surroundings and associations. It was your father that specially urged me to it; and since he interested himself so much in me

GREGERS.

My father did?

HIALMAR.

Yes, you surely knew that, didn’t you? Where do you suppose I found the money to learn photography, and to furnish a studio and make a start? All that costs a pretty penny, I can tell you.

GREGERS.

And my father provided the money?

HIALMAR.

Yes, my dear fellow, didn’t you know? I understood him to say he had written to you about it.

GREGERS.

Not a word about his part in the business. He must have forgotten it. Our correspondence has always been purely a business one. So it was my father that — !

HIALMAR.

Yes, certainly. He didn’t wish it to be generally known; but he it was. And of course it was he, too, that put me in a position to marry. Don’t you — don’t you know about that either?

GREGERS.

No, I haven’t heard a word of it.

[Shakes him by the arm.]

But, my dear Hialmar, I can’t tell you what pleasure all this gives me — pleasure, and self-reproach. I have perhaps done my father injustice after all — in some things. This proves that he has a heart. It shows a sort of compunction —

HIALMAR.

Compunction — ?

GREGERS.

Yes, yes — whatever you like to call it. Oh, I can’t tell you how glad I am to hear this of father. — So you are a married man, Hialmar! That is further than I shall ever get. Well, I hope you are happy in your married life?

HIALMAR.

Yes, thoroughly happy. She is as good and capable a wife as any man could wish for. And she is by no means without culture.

GREGERS

[rather surprised.]

No, of course not.

HIALMAR.

You see, life is itself an education. Her daily intercourse with me — And then we know one or two rather remarkable men, who come a good deal about us. I assure you, you would hardly know Gina again.