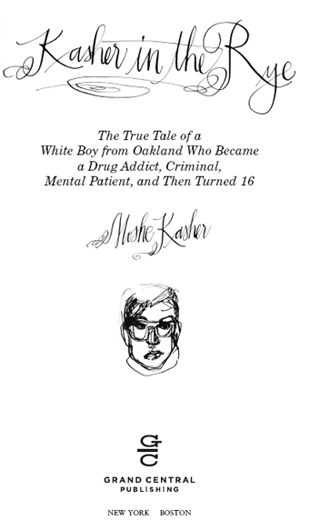

Kasher In The Rye: The True Tale of a White Boy from Oakland Who Became a Drug Addict, Criminal, Mental Patient, and Then Turned 16

Authors: Moshe Kasher

For my mother. I wouldn’t be here without you

.

I didn’t even know this thing was a book, and without the help of many, it probably wouldn’t have been. Many thanks are due. First and foremost to my manager, Josh Lieberman, for having the vision to crush my dream of putting on a one-man show while building a new vision for me that became this book. To the master, Richard Abate, for handing me the building blocks and teaching me how to stack them. To my editor, Ben Greenberg, for his faith in me and for putting my manuscript and talents to the whetstone. Together we made something razor-sharp. To Flag Tonuzi, for designing the perfect cover for this book. To everyone else at Grand Central. To all the kids I grew up with in Oakland, for teaching me how to survive. Thanks to Oakland Public Schools, OPD, every therapist I ever had, every adult I ever hated, and everyone who made a mistake with me. I ain’t mad acha. To everyone at the Gersh Agency and to Dave Becky and everyone at 3arts. To every stand-up who inspires me. To

everyone I forgot: I didn’t mean it. To every gangster rapper, ever (especially those whose songs made my chapter list). To all my dear friends, especially my brother from another mother, Mr. Moon, for allowing a sliver of his story to be told by me, and for living his life with me all these years. To Jeremy Weintraub, for his help and support. To John Rose, for helping me untie the knot. To the chief conductor, for all the music. To Arlene and John. To Larry Wilhoit, the finest step entemologist I could have asked for. To my entire wild, insane, brilliant family: Kashers, Swirskys, Sterns, Worthens, etc. A very special thanks to my brother from the same mother, David Kasher, the world’s sexiest rabbi, for the constant patience, feedback, love, and criticism, and for helping me name this book. And finally, always, to Oakland.

About the Artwork

Each of the inserts you see throughout the book demarcating its different sections was drawn by Oakland artist and graffiti legend Eskae aka Ezra Li Eismont. I first met Ezra when I also used to write graffiti back in the day, and when I hung up my paint can due to a lack of any measureable artistic talent, Ezra did the world a favor and kept painting. He is now an internationally recognized artist and a real good guy. Check out his work at

www.ezrali.com

.

Also, all of the calligraphy you see was hand drawn by Emily Snyder, a master calligraphy artist and owner of the business

www.queenofquills.com

. Have her write something for you.

The names in this book have been changed to protect the guilty and the innocent. With one odd exception. The documents that

I have included throughout the book are, you might notice, describing someone named “Mark Kasher.” Yes, that’s me. Like many American Jews I was given a “slave name” in order not to arouse suspicion should the Gestapo ever make a resurgence here in the USA. Mark is the Toby to my Kunte Kinte. At about sixteen, I began going full-time by my middle name, Moshe. I was feeling a desperate need to re-create myself with a new identity. Read the book and you’ll soon see why.

Memoirs are inexact things, messy around the edges and distorted by the twists and turns of memory. Sometimes details get lost or hazy and confusing. I’ve been in the middle of telling a story only to realize, “Oh shit, this didn’t happen to me, this is a Steven Segal film plot.” Although, strangely, I did once rescue the President from hijackers on a plane. See, there we go again. You’ll never know if that last part is true.

As you go back through the creaky secret rooms of your memory, you find places damaged by time and neglect. You can dust them off, but often you want to present them in a form that is understandable to people, and I can imagine polishing a corroded memory and making it prettier or more compelling than it deserves to be.

Under the weight of all of that, I would like to offer you my memoir: a drug-filled journey through the harrowing years of my youth. I have tried as best I can to give it over with honesty and

accuracy. But you’ll be shocked to realize that a drug-addicted, mentally ill journey of violent insanity is a bit of a hazy cat’s-cradle to untangle. Hazy or not, this is my life.

I even found, at points, when diving into my memory that

I

was surprised at how bad things had gotten when I was young. Surprised by my own memories. Do you remember that scene from the movie

The Princess Bride

when, after Princess Buttercup is swallowed by the Snow Sands in the Fire Swamp, Westley cuts a vine from a nearby tree and dives in after her? He’s in there, breathless, blind, feeling around for what’s important. That’s how I felt the entire time I was swimming around in my memories. I felt swallowed by them, and only the lifeline of my adult brain made me feel safe and like I’d emerge again, able to breathe.

Writing this book was painful and illuminating, exciting and emotional. I can only hope that reading it makes you feel that way, too. When I was a very young man I remember reading books like

Catcher in the Rye

and

The Basketball Diaries

and thinking secretly, “Look, here are people who are just as broken as me.” It gave me a private thrill to know that I wasn’t the only piece of damaged machinery out there. So I suppose I’d like to say to the person who’s reading this book who feels like I did when I was young—like a factory defect from the human being plant: I get it. You’ll be okay. Hell, maybe someday you’ll even write a book about it.

“The Dayz of Wayback”

—

NWA

I was born ugly. Babies are ugly. At least I’ve always thought so. Little pruny creatures. Shooting down the birth canal, the final seconds of prelife bliss tick to a sudden stop and a gross little

thing

is bungeed into the world. Leaving behind the vaginaquarium floating bliss of yesterday, it pops into the world. Here comes Baby, covered in gel and matter, wrinkles and blood, shit and life juices. I’ve always imagined a mother looking down and in the first millisecond thinking, “Goodness,

what

is

that

?” But before she even has a chance for that thought to shoot up her synapses and reverberate in her mind, the doctor smacks Baby’s bottom and the little one shrieks its first cry. That cry, quick as sound, quicker, jams itself into its mother’s ears, derailing that first repulsed thought. It circumvents her brain. It shoots into her heart. Mommy forgets all about that first thought when she hears that wail. Her only thought now is, “My son!”

My mother never heard that wail. My mother is deaf.

My shriek flew up to her ears and, finding two broken, swollen drums, ricocheted back and meandered around the hospital room looking for somewhere to roost before it impotently spilled onto the hospital floor.

And though her second thought no doubt was a loving one, I’ve always wondered if that first “Eww, gross,” thought didn’t make it to my mother’s brain and, planting itself deep inside her, make her ask, years later, “What is wrong with this kid?”

My earliest memories are of flying fingers. Flesh-colored strings zapping through the air, signifying meaning. I didn’t realize my first word was “spoken” in sign language. How would I have known that wasn’t just how everyone talked?

I didn’t realize my mother was deaf, but I did realize that if I cried when she wasn’t looking, it made no difference to her. If I wept in view of her, her face would screw up in compassion and she would reach down and scoop me up to make me feel okay again. I took this information and imprinted it into my brain.

As early as I can recall, adults have been telling me there was something wrong with me. I was passed around, adult to adult, each one throwing their hands up and declaring, “I don’t know what’s wrong with him either!” Adults talked about me like that, right in front of me, all the time, as if my mother’s deafness somehow applied to me by association. I’d spend time in the mirror, trying to figure out what was looking back at me, what weird alien thing I was.