Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist (30 page)

Read Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist Online

Authors: Patrick Moore

Researchers have developed a treatment for sea lice on farmed salmon called SLICE. It is a medication that is put in the salmon feed and it kills the lice. Activists are now campaigning against the use of this medicine, even though it has been approved by health and environmental authorities in many countries. This is typical: they are against the lice, claiming the lice will exterminate wild salmon, and then they are against the cure, even though there is no evidence of harmful side effects.

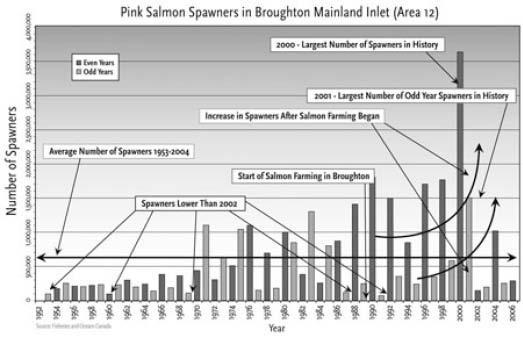

Amid the claims of wild-eyed activists that the pink salmon were going extinct, 2009 saw a bountiful run. This extended from Alaska to Washington State, including the Broughton Archipelago and the Campbell River, where there is the greatest concentration of salmon farms.

[12]

There were so many fish that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans opened the pink salmon fishery for commercial boats in order to prevent an overabundance of salmon in the spawning streams. In 2009 nearly one million pink salmon reached the spawning grounds. This is pretty much as much proof as you can get in the real world that they are not going extinct and that the salmon farms are not damaging wild salmon stocks. Yet these zealots don’t give up easily.

The runs of coho, chinook, and chum salmon were also plentiful in 2009. The only salmon run that was really depressed that year was the Fraser River sockeye. Over 10 million were expected and only 1.7 million showed up. Alexandra Morton immediately blamed the shortage of sockeye on lice from salmon farms in the Broughton, far from the Fraser River, something she had never mentioned before. She and her partners in distortion completely ignored the huge pink salmon returns. And a willing media complied in one of the most blatant examples of bias and fabrication I have seen. Not one major Canadian newspaper reported that the pink salmon run had returned in abundance, completely disproving the trumped-up charge that they were nearly extinct.

If the bountiful pink salmon runs of 2009 were not sufficient to convince the media and the public that sea lice are not a problem, then 2010 leaves no doubt. Not only did the pink salmon once again return in near-record numbers, the Fraser River sockeye run was estimated at 34 million fish, the largest run in nearly a century.

[13]

Yet the willing accomplices in the media (such as Mark Hume of the Toronto Globe and Mail) have remained silent and the activists warn that one good run doesn’t mean much. Their credibility has been shattered beyond repair with both the public and fisheries scientists. Carl Walters, arguably the most knowledgeable salmon population biologist in Canada, put it this way, “My personal opinion is that the claims about fishfarming effects on either of those species [pink and sockeye] are bogus. It is certainly not a matter of fact that fish farming has affected those populations. It is quite unlikely that fish farming has anything to do with the changes in sockeye-salmon numbers that we’ve seen, the downs or ups.”

[14]

Wild salmon populations are subject to a wide range of environmental factors that influence their survival. Perhaps the most important of these is what researchers call “ocean conditions”. During their years at sea, salmon are subjected to predators, disease, fluctuating abundance of feed, varying temperatures, and competition from other species. All these factors combine to determine their success at returning to their natal streams to spawn. The past ten years have demonstrated that it is difficult to predict with accuracy how many salmon will return in a given year because there are many variables and the fish are far at sea where direct observation is impossible. But we can conclude that the evidence is overwhelming that sea lice are not a significant factor in salmon survival.

The feed for farmed salmon contains fishmeal and oil from wild fish. This results in a net loss of protein for a hungry world because it takes two to three pounds of wild fish to make one pound of farmed salmon.

It is true that a portion of the feed for farmed salmon is fishmeal and oil from wild fish. The omega-3 fats in fish oil are essential for good health in salmon and other farmed fish. But it is not true that the use of these products results in a net loss of protein for consumers. When you think about it, why would fish farmers be so stupid as to employ a system that made less food for people? The fact is they don’t; aquaculture produces more food for people or it would not make any sense. An independent study done for the European Union Research Director concluded, “Globally the efficiency of consuming fish directly and eating animals fed on fishmeal and fish oil is about equal. Feed conversion figures for salmon suggest that it is more efficient to consume salmon derived from aquaculture than wild caught fish.”

[15]

Fishmeal and fish oil are derived from three main sources: the scraps from processing wild and farmed seafood, undesirable fish caught incidentally while fishing for other species, and from fisheries that target fish such as menhaden and anchovies caught specifically for fish meal. The anti-salmon farm brigade focuses most of its attention on the anchovy fishery, a well-managed and sustainable harvest that lands five million tons per year, or about 5 percent of the global wild seafood catch. The gist of the its criticism is that salmon farmers are taking food from the mouths of poor Peruvians and producing food for affluent consumers in rich countries. And by feeding the fishmeal and oil made from anchovies to salmon there is a net loss of protein as it takes two to three pounds of anchovies to make one pound of salmon. It’s a great story about corporate greed and abuse of poor people, but there isn’t a speck of truth to it.

First, not even poor people want to eat a regular diet of anchovies. We do have to take people’s tastes into account. It might well increase the food supply if we all ate algae paste three meals a day, but that isn’t likely to become a fad anytime soon. Second, anchovies spoil very quickly after they are caught: that is why they are usually canned in oil with a lot of salt. Some people, myself included, enjoy the occasional one on a Caesar salad. But the only other way to keep them for a reasonable time is to freeze them. There simply isn’t a market for five million tons of frozen anchovies. That is why they are converted to meal and oil. If people wanted to eat them as anchovies, there would be a market for them and they would not be rendered down. Food fish always command a higher price than fish that go into rendering plants. I suppose one could argue that the government of Peru should buy all the anchovies and give them, and a deep-freeze, and the power to run it, to the poor. The export of anchovy meal and oil is one of Peru’s largest income earners. It surely does Peru more good to bring in foreign currency than it would to make the people eat five million tons of anchovies every year. Yet the activists, and even some wooly-headed academics, continue to argue this point.

Whatever your thoughts on developing countries and poor people, it doesn’t make sense to blame salmon farmers for keeping Peruvians down on the farm. And only about one-third of the world’s fishmeal and oil is consumed by aquaculture, the majority is fed to chickens and pigs. Why? Because it’s good for their health just as it’s good for our health. As aquaculture grows, it will consume a larger share of these feeds, because fish have better conversion rates, so fish farmers can afford to outbid land-based farmers. Eventually the limited supply of fishmeal and oil will become a constraint to the growth of aquaculture. That’s why a tremendous amount of research is now focused on replacing fishmeal and oil with substitutes such as soybeans and other crops grown in abundance on land. Already a genetically enhanced soybean has been engineered to produce omega-3 oils. This and other innovations will eventually revolutionize the human diet and the diets of our domestic animals, with positive results all around for health and nutrition.

Fish farmers feed salmon artificial chemical dyes to make them look pink like wild salmon.

This is one of the most preposterous allegations, but it is repeated in the activist rant against aquaculture. Again it is simply the use of propagandist language—turning a good thing into a toxic threat—that gives consumers the impression farmed salmon is somehow “artificial.”

True, naturally occurring chemicals called carotenoids are added to salmon feed and this gives the salmon a distinctive color. These are, in fact, the same carotenoids that make wild salmon pink. They come through the food chain from the plankton that produce them in the first place. These same carotenoids also make shrimp and crabs pink and that is why shrimp farmers add them to their feed as well.

It is also a fact that these carotenoids—namely, astaxanthin and canthaxanthin—are produced synthetically and used as additives in the feed of fish and of poultry (to give the skin and egg yolks a brighter yellow color) and as colorants in and on a wide variety of foods. These carotenoids benefit human health and are essential nutrients for salmon.

[16]

They are powerful antioxidants, sold as health food supplements and sunless tanning treatments.

[17]

Carotenoids make carrots orange (and they

are

good for our eyesight), daffodils yellow, and prepared meats pink rather than gray. Adding them to food for nutritional or aesthetic reasons is perfectly safe and in many cases beneficial. It is no different than adding vitamin C to fruit juice as a dietary supplement—and, yes, vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is also made synthetically and is no different from the “natural” vitamin C produced in citrus fruits. Should products with added vitamin C be labeled “contains the artificial chemical ascorbic acid”?

This graph shows that there have actually been more salmon spawning in the Broughton Archipelago since salmon farming began than there were before. In 2009 nearly one million fish returned to the spawning beds, despite predictions by activists that they faced extinction.

Farmed salmon contain high levels of cancer-causing PCBs and dioxins.

Enter the classic food scare, complete with images of pregnant women and babies threatened by toxic chemicals in their diet. It is a fundraiser’s delight and millions of dollars are spent, and even more millions raised, on orchestrated media campaigns to make sure the scare is spread far and wide. How about some facts?

Yes, farmed salmon contain minute traces, in the parts per billion (equal to one penny out of $10,000,000), of PCBs and dioxins. But so do milk, cheese, butter, beef, chicken, and pork. The levels of these chemicals in all these foods are so far below what is considered a risk to health that it isn’t worth talking about; but it is worth fear-mongering in order to fabricate campaigns, make media headlines, and bring in the big grants and donations.

Interestingly, scientists have new evidence that some long-lived chemicals thought to be entirely human-made pollutants, such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs)—the latter are used as flame-retardants in furniture and clothing—actually have significant natural sources. Most of the PBDEs found in the blubber of a stranded True’s beaked whale, which was found in Virginia in 2003, were found to have a natural origin.

[18]

The natural sources of PBDEs found in the whale are still unknown; scientists only know they aren’t from human activity. Even more important from a health perspective is the fact that these natural chemicals likely explain why whales, humans, and other animals have enzymes that can break down PCBs, PBDEs, and other pollutants. That’s why, from a health perspective, the parts per billion of these chemicals in our foods is of no health consequence.

This is a story of conspiratorial proportions with politicians, lobbyists, fishermen, charitable foundations, and activist groups all lined up to deliver the knock-out punch to salmon farming. Yet farmed salmon sales continue to rise, and one must admire the intelligence of the consumer who sees through the hype and buys one of the healthiest foods on the market, one that is available year-round at a reasonable price.

In September 2004 the journal

Science

carried a report that concluded that farmed salmon had higher levels of PCBs than did wild salmon.

[19]

PCBs, now banned, are an oily compound that was used in power line transformers as a coolant. The activist scientists who conducted the research were paid by the Pew Charitable Trust. The latter is an advocacy group based in Philadelphia that has billions of dollars in assets as a result of a legacy from the Sun Oil Corporation. Coincidentally the advisory board to Pew included a former governor of Alaska and a representative of the Alaska seafood industry. It just so happens that the main competition for “wild” Alaskan salmon sales in the U.S. is farmed Chilean and British Columbian salmon (we will get to why I put “wild” in quotations shortly). Other powerful figures to wade into this campaign were Alaskan Frank Murkowski, then governor, and his daughter, U.S. Senator Lisa Murkowski. The

Science

article made headlines around the word while salmon farmers watched and wept. The whole episode was framed as a threat to health posed by farmed salmon. Most media reports did not even mention the fact that wild salmon was also shown to contain PCBs, although supposedly at lower levels. The impression was given that farmed was toxic and wild was safe.