Authors: David Van Reybrouck

Congo (49 page)

I found a good spot and waited for Baudouin at the station, close to the railroad workers’ monument. Everyone wanted to see him, he was a handsome boy, but there were soldiers with rifles everywhere. It was impossible, but my power allowed me to slip past. I wanted to give the king some flowers, to show my love for him, but then I saw that long, shiny sword and I took it

pour la folie

, just for fun. I got five meters away, then I heard the soldiers loading their weapons. King Baudouin said: “No guns.” I walked back to him and said: “I wish you a fine visit to Congo. The Lord was the one who urged me to take your sword. We will travel to parliament together as good acquaintances. It is time that we become independent. The European women are like the Virgin Mary, but later the good Lord will grant us the peace to be able to marry white women. Belgium is far away, as far as heaven, a common property where there must be black people as well. A common market. The blacks will go to Belgium. I am not insane, I am normal. I give you your sword back.” Baudouin replied: “No one may hit you! I am going to give you a gift. Don’t forget me. It’s true, later you will marry a white woman, on condition that you learn French.” But he left the same day, without giving me a gift. He never kept his promise.

Whether this remarkable conversation actually took place is very much in question. In it, mysticism and eroticism collide ingeniously with European current events (the common market!) and Belgian linguistic rivalry (learning French!). But that a man with a rather idiosyncratic way of thinking remembered independence, fifty years after the festivities, as a promise never kept says a great deal in itself. Today, through the fissures in his bizarre fable, there shines the light of a profound truth: independence should have been a gift, but it remained an empty promise.

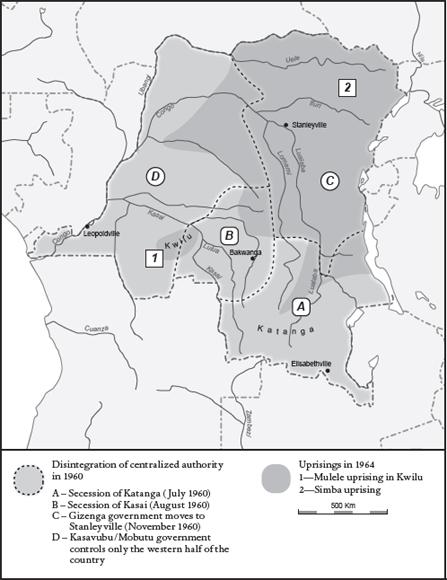

MAP 7: THE FIRST REPUBLIC: SECESSIONS AND UPRISINGS

The Turbulent Years of the First Republic

E

VERYONE KNEW THERE WOULD HAVE TO BE A GOOD DEAL OF

improvising during that first period after independence. That things would not run smoothly as burnished silk was only to be expected. But that Congo, during the first six months of its existence, would have to deal with a serious military mutiny, the massive exodus of those Belgians who had remained behind, an invasion by the Belgian army, a military intervention by the United Nations, logistical support from the Soviet Union, an extremely heated stretch of the Cold War, an unparalleled constitutional crisis, two secessions that covered a third of its territory, and, to top it all off, the imprisonment, escape, arrest, torture, and murder of its prime minister: no, absolutely no one had seen that coming.

And it would take a long time for things to get better. The period between 1960 and 1965 is known today as the First Republic, but at the time it seemed more like the Last Judgment. The country fell apart, was confronted with a civil war, ethnic pogroms, two coups d’état, three uprisings, and six government leaders (Patrice Lumumba, Joseph Ileo, Justin Bomboko, Cyrille Adoula, Moïse Tshombe, and Évariste Kimba), two—or perhaps even three—of whom were murdered: Lumumba, shot dead in 1961; Kimba, hanged in 1966; Tshombe, found dead in his cell in Algeria in 1969. Even Dag Hammarskjöld, the secretary general of the United Nations, the man who headed a reluctant world government, lost his life under circumstances that still remain unclear—an event unparalleled in the history of postwar multilateralism. The death toll among the Congolese population itself during this period was too high for meaningful estimates.

Congo’s First Republic was an apocalyptic era in which everything that could go wrong did go wrong. Both politically and militarily, the country was plunged into total, inextricable chaos; at the economic level, the picture was clearer: things simply went from bad to worse. Yet Congo had not fallen prey to wild irrationality. The misery of the first five years was not the product of a renaissance of barbarism, of the revival of some form of primitivism repressed during the colonial years, let alone of any opaque “Bantu soul.” No, here too the chaos was a result more of logic than of unreasonableness, or rather of the collision of disparate logics. The president, the prime minister, the army, the rebels, the Belgians, the United Nations, the Russians, the Americans: each of them wielded a form of logic that seemed consistent and cogent within the confines of their own four walls, but which often proved irreconcilable with the outside world. As in theater, tragedy in history here was not a matter of the reasonable versus the unreasonable, of good versus bad, but of people whose lives crossed and who—each and every one of them—considered themselves good and reasonable. Idealists faced off with idealists, but when believed in fanatically all forms of idealism lead to blindness, the blindness of the good. History is a gruesome meal prepared from the best of ingredients.

The turbulent first five years of Congo can be divided into three phases. The first ran from June 30, 1960, to January 17, 1961, the day on which Lumumba was murdered. During the first six months, the house of cards of the colonial state collapsed, and “the Congo crisis” dominated world news week after week. The second phase coincided with the years 1961–63, and was marked primarily by the Katangan secession. It ended when the rebel province, after forceful UN military intervention, rejoined the rest of the country. The third phase started in 1964, when a rebellion broke out in the east and spread across half the country. The central authorities regained control of the territory only with the greatest of difficulty. The year 1965 was to have witnessed a return to normalcy, but ended unexpectedly on November 24 with Joseph-Désiré Mobutu’s coup d’état, a putsch that defined the country’s history. Mobutu remained in power for the next thirty-two years, until 1997. That was the so-called Second Republic, a regime that, strictly centralized at first, ultimately developed into a dictatorship.

The First Republic was characterized by a jumble of the names of Congolese politicians and military men, European advisers, UN personnel, white mercenaries, and native rebels. Four of those names, however, dominated the field: Joseph Kasavubu, Lumumba, Tshombe, and Mobutu. In terms of complexity and intensity, the ensuing power struggle between them was like one of Shakespeare’s history plays. The history of the First Republic is the story of a relentless knockout race between four men who were asked to play the game of democracy for the first time. An impossible mission, all the more so when one considers that each of them was hemmed in by foreign players with interests to protect. Kasavubu and Mobutu were being courted by the CIA, Tshombe at moments was the plaything of his Belgian advisers, and Lumumba was under enormous pressure from the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Nations. The power struggle among the four politicians was greatly amplified and complicated by the ideological tug of war taking place within the international community. It is hard to serve democracy when powerful players are constantly, and often frantically, pulling on the strings from above.

What’s more, none of these men had ever lived under a democracy in their own country. The Belgian Congo had had no parliament, no culture of institutionalized opposition, of deliberation, of searching for consensus, of learning to live with compromise. All decisions had come from Brussels. The colonial regime itself was an executive administration. Differences of opinion were kept hidden from the native population, for they could only undermine the colonizer’s prestige. In his seemingly unassailable omnipotence, the highest authority, the governor general with his white helmet decked out with vulture feathers, seemed more like the chieftain of a feudal African kingdom than a top official within a democratic regime. Is it any wonder then that this first generation of Congolese politicians had to struggle with democratic principles? Is it strange that they acted more like pretenders to the throne, constantly at each other’s throats, than like elected officials? Among the historical kingdoms of the savanna, succession to the throne had always been marked by a grim power struggle. In 1960 things were no different.

And in fact, wasn’t it all about who was going to take over from King Baudouin? Kasavubu was the first and only president of the First Republic. The dress uniform he had designed for himself was an exact copy of Baudouin’s. Léopoldville and Bas-Congo supported him en masse. Only rarely was his position as head of state openly called into question, but in 1965, Mobutu—whose own ceremonial uniform later proved to be a copy of Baudouin’s as well—shoved him aside.

Lumumba’s power base lay to the east, with Stanleyville as its center. He was the most popular politician in Congo, but he resented having to bow to Kasavubu as president. He would only survive the first six months of the First Republic, but after his death his intellectual legacy continued to play a major role in Congolese politics.

Tshombe was perhaps even more resentful. His party had received the short end of the stick during the formation of the new government. He himself had no choice but to settle for the position of provincial governor general of Katanga in Elisabethville. And even though that position—in terms of square kilometers and industrial importance—was comparable in weight to that of a German chancellor in a united Europe, he had to face the fact that the true center of power lay elsewhere, in Léopoldville.

On the day of independence itself, Mobutu, finally, was the least significant of the four: he was Lumumba’s private secretary. He had no major city backing him, as the other three did, let alone a powerful people like Kasavubu (among the Bakongo) or Tshombe (among the Lunda). He came from a small tribe in the far north of Équateur, the Ngbandi, a peripheral population group that did not even speak a Bantu language like the rest of Congo. At twenty-nine he was also the youngest of the group (Kasavubu was forty-five, Tshome forty, Lumumba thirty-five). But five years later he was lord and master. He would develop into one of the most influential persons in Central Africa and one of the richest men in the world. The classic story of the errand boy who becomes a Mafia kingpin.

D

URING THE FIRST ACT OF

C

ONGO

’

S INDEPENDENCE

, Patrice Lumumba was incontestably the pivotal character. All eyes were turned on him after his inflammatory speech during the transfer ceremony. When the curtain went up on the Congolese drama, he was a dynamic people’s tribune, adored by tens of thousands of common folk. Only a few scenes later he was despised, spit upon, and forced to eat a copy of his own speech.

July 1960. The dry season. A cobalt blue sky. The independence party had lasted four days. The army, the Force Publique, kept order as always. The newly independent Congo may still have been sailing against the current—the political institutions may still have been in their infancy, governmental experience may have been null, the challenges were perhaps enormous—but the armed forces were solid as a rock. The officers’ corps was still Belgian: a thousand Europeans maintained command over twenty-five thousand Congolese. The chief commander was still General Émile Janssens, the man who had so rigorously quashed the 1959 riots. Without a doubt the most Prussian of all Belgian officers, he was a great soldier with a rigid mind: discipline was sacred to him, protest was a defect, chaos the sign of weak character. He had to put up with being answerable to Lumumba, who was not only prime minister but had also been made minister of national defense. Concerning him, Janssens would later write: “Moral character: none; intellectual character: entirely superficial; physical character: his nervous system made him seem more feline than human.”

1

That was how things lay: Congo was independent, true enough, but the Belgians not only ran things economically, they also maintained a total grip on the military apparatus.

Fireworks had graced the night sky on Thursday, June 30, but by Monday, July 4, things were already awry. Congo’s existence as a stable country lasted only a few days. During the afternoon parade at the Leopold II barracks, a few soldiers refused to obey orders. General Janssens intervened and did what he had always done in such cases: demoted the recalcitrant elements on the spot. This time, however, that move backfired. The next day some five hundred soldiers gathered in the mess hall to express their dissatisfaction. The soldiers were tired. For the last eighteen months they had been zigzagging across the country, putting down minor insurrections. They yearned for opportunities for advancement within the military hierarchy, for better pay and less racism. Shortly before independence, they had written:

No one has forgotten that within the Force Publique we, the soldiers, are treated like slaves. We are punished arbitrarily, because we are Negroes. We have no right to the same advantages or facilities as our officers. Our two-person rooms are extremely small (7.5 m

2

[about 79 square feet] of floor space) and have no furnishings or electricity. We eat very little and our food in no way complies with the rules of hygiene. The wages we are given are insufficient to meet the current cost of living. We are not allowed to read newspapers published by blacks. One need only be caught with a copy of

Présence Congolaise

,

Emancipation, Notre Congo

. . . to receive two weeks in the brig. After this unjust punishment one is then transferred to the disciplinary camp at Lokandu, where one is taught to live in military fashion . . . . In the Force Publique our officers live like Americans; they have better housing, they live in big, modern houses, all furnished by the Force Publique, their standard of living is very high, they are arrogant and live like princes; all this in the name of prestige, because they are white. Today it is the unanimous desire of all Congolese soldiers to have access to positions of command, to receive a respectable salary and to put an end to every form of discrimination within the Force Publique.

2