Authors: David Van Reybrouck

Congo (77 page)

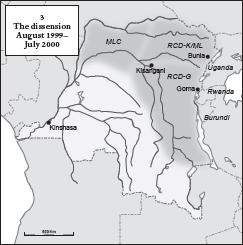

Kabila’s foreign allies (most notably Angola and Zimbabwe) put an end to the rebels’ advance. The front stabilizes. In the east of the country, the rebels are still engaged by the Mai-mai, and the Rwandan Hutu militias supported by Kinshasa. Uganda sets up a second rebel movement: the MLC. The Lusaka Peace Agreement proves ineffective.

With Kinshasa beyond reach, attention is turned to the available booty. But the dividing of it leads to dissension. The rebel movement falls apart into a pro-Rwandan and a pro-Ugandan schism: the RCD-G (for Goma) and the RCD-K (for Kisangani), respectively. Rwanda tries to take Kisangani, a major diamond center, away from Uganda. After an initial confrontation in August 1999, the RCD-K flees to Bunia and becomes the RCD-ML. In May and June of 2000, Rwanda takes Kisangani.

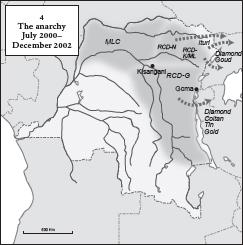

In the north, the rebellion crumbles completely. Pro-Ugandan rebels no longer fight against Kinshasa or pro-Rwandan rebels, but simply among themselves. New, smaller armies come along. In Ituri, the snarl of interests can no longer be disentangled. In the end, the motif is that of plundering, even in Rwandan-controlled territory. The 2002 peace agreement pacifies a large part of the area. The MLC and RCD-G are allowed to put forward a vice-president, but in Ituri and Kivu the conflict simmers on for years.

Yet a simple cartographic comic strip is all one needs to understand the course of events. The conflict took place in three phases. From August 1998 to July 1999 Rwanda, along with Uganda and a makeshift native rebel army, tried to overthrow Kabila. They did not succeed. That phase ended with the signing of the Lusaka Peace Agreement, which did a great deal, but brought no peace. The second phase ran from July 1999 to the end of December 2002. Rwanda and Uganda no longer tried to advance on Kinshasa, but now, with the help of local militias, controlled one-half of Congo’s territory, allowing them to help themselves on a massive scale to the raw materials present there. Now that booty had taken precedence over power, schisms arose within the rebellion and there were violent confrontations in Kisangani. This turbulent phase ended with the Pretoria peace agreement in December 2002, which was to enter into effect in June 2003. The Rwandans and Ugandans withdrew to their own countries and the United Nations increased its presence. That put an official end to the war; unofficially, however, things went differently. The third phase began in 2003 and, in Kivu, is still going on today. During this long period the war has been limited to the extreme eastern part of Congo, in those areas that border directly on Uganda (Ituri) and Rwanda (Kivu). Those zones have been subjected to bouts of extreme violence, massive human rights violations, and incredible human suffering.

In each of its phases the conflict was characterized by the aftershocks of the Rwandan genocide, the weakness of the Congolese state, the military vitality of the new Rwanda, the overpopulation of the area around the Great Lakes, the permeability of the former colonial borders, the growth of ethnic tension due to poverty, the presence of natural riches, the militarization of the informal economy, the world demand for mineral raw materials, the local availability of arms, the impotence of the United Nations, and so on and so forth.

On June 25, 2007, in the Rwandan capital of Kigali, I had breakfast at the celebrated Hotel des Milles Collines, the place of refuge during the genocide that served as inspiration for the film

Hotel Rwanda

. It was still an exorbitantly expensive multistar hotel. I did not spend the night there, but arrived that morning for an interview with Simba Regis, an introverted Rwandan war veteran only a few years older than I. At the buffet we used tongs to pick out croissants glistening with butter. The waitress brought us wonderfully fresh fruit juice. Simba Regis was born in 1967 and his life story reflects the history of the Rwandan Tutsis in a nutshell. In 1959, when the Hutu uprisings began, his parents fled to Burundi. He was born there, but throughout his childhood and youth he was constantly reminded that not Burundi, but Rwanda was his homeland. He sympathized with the struggle of the Tutsis in exile and went to southern Uganda in 1990 to join up with Kagame’s army, the Rwandan Patriotic Front. He took part in the invasions of Rwanda, he was among the first to reach Kigali, and he escaped the genocide of 1994 by the skin of his teeth. “Six-year-old children lay there wasting away, young mothers were slaughtered by the Interahamwe. It was maddening. When you’ve seen that, you have to put up a fight.” And so he was there in 1996 when Rwanda first invaded Congo to neutralize the Hutu threat. And in 1998, during the second Rwandan invasion, he was once again in the front lines; this time too—in addition to dethroning Kabila—the elimination of the remaining Hutu militias was a major objective. Thousands of Rwandan Hutus were still hiding in the forests of eastern Congo and, more than ever after the AFDL massacres, were out for vengeance.

The fighting began on August 2. Rwanda received backing from Uganda and Burundi, who were also worried about the rumbling on their western borders and knew of the mineral riches of the eastern Congo. Goma and Bukavu fell immediately. Two weeks later, rumor had it that the conquests had been the work of a Congolese rebel movement, the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie (RCD). Ernest Wamba dia Wamba, a former history professor, was pushed forward as its leader. But the RCD was as much a phantom construction as the AFDL had been in 1996. As he slowly picked apart his croissant, Simba Regis spoke of that in no uncertain terms. “We trained those rebels. Rwanda was simply better organized. The Congolese wore Rwandan uniforms and boots. They were under our command. We were their godfathers.”

Simba Regis fought on Congolese territory for four years, from 1998 to 2002, the full length of the official war. He was in Katanga and in Kasai. On occasion the Rwandans fought against the Interahamwe and the Mai-mai, who were supported by Kabila, but usually nothing happened at all. “On faisait la vie,” he said, “we made a living,” by which he seemed to suggest that exploitation of the mineral resources was more important than waging war. Katanga was still brimming over with raw materials, Kasai was still extremely rich in diamonds. The fight against the organized Hutus he referred to as “just and noble,” but he was sick and tired of war as a way of life. “I’m finished. I’ve been at war ever since 1990. The ones who make the decisions about the war are never the ones fighting, but I lost my brothers and my friends. There were eleven of us, all friends from Bujumbura; we came from the same neighborhood and went to the same elementary and secondary schools. Of those eleven, two are still alive. Me and someone who lives in Canada.” The patio outside the breakfast room looks out over Kigali. The city glistens in the morning light. “When I’ve been drinking beer, I have nightmares. I see houses being blown up. I see my friends crying because they’ve lost an arm or a leg. And I’m always powerless, I can’t do anything to help. Then I wake up with a start. I can still taste the war. I’ve had a bad life, really. I want to go to Europe, because in five or ten years’ time things are going to explode here again.”

17

James Kabarebe thought the job would be over quickly. In 1996 it had taken his forces seven months to get to Kinshasa: this time he could do better. His plan was as risky as it was audacious. At Goma airport he hijacked a few planes, filled them with RCD soldiers and forced the pilots to fly to the west, to the military base at Kitona on the Atlantic Ocean. From there it was only four hundred kilometers (250 miles) to Kinshasa. His air link seemed to work: on August 5 he took Kitona and succeeded in convincing the soldiers present—most of them demotivated former FAZ soldiers being “reintegrated” into the new army—to help him fight against Kabila. On August 9 they took the crucial port town of Matadi, on August 11 the Inga hydroelectric plant. Kabarebe now had his finger on Kinshasa’s switch and could cut off the capital’s power supply. Night after night, he plunged the hungry megalopolis into darkness. Anti-Tutsi sentiment flared up in the working-class neighborhoods. A few hundred Tutsis or people with Tutsi features were lynched by the crowds in a horrible fashion. As in the South African townships, a car tire was hung around their neck, filled with gasoline, and then ignited.

All indications were that Kinshasa would soon fall. Kabila’s army was no match for Kabarebe’s troops. Still, things took a different turn. Kabila was saved in the nick of time by foreign troops: on August 19, 1998, four hundred Zimbabwean soldiers entered Congo; on August 22, the Angolan army began the liberation of Bas-Congo. Angola’s role was particularly decisive. During the First Congo War it had remained neutral: no one in Luanda mourned the imminent departure of Mobutu, whose support for the right-wing UNITA rebels had caused so much suffering. During the Second Congo War, however, the cards were reshuffled. There was a distinct possibility that, in order to bring down Kabila, Rwanda would this time support UNITA. That could not be allowed to happen. Zimbabwe, on the other hand, had interests in Katangan mining operations and therefore more economic motives. In addition, a sort of ideological brotherhood existed between presidents Robert Mugabe, José Eduardo Dos Santos, and Kabila; all three had flirted with what is referred to in Africa so exquisitely as

le marxisme tropicalisé

(tropicalized Marxism). Fidel Castro had supported Angola for years, just as he had Kabila with the visit from Che Guevara. During his time as President Kabila’s bodyguard, Ruffin Luliba had noticed those close ties. “

Mzee

liked revolutionaries. Men like Mugabe and Castro, he thought they were wonderful. His personal physician was a Cuban. I went with him to Cuba a few times. There were four of us

kadogos

, and we went to see Castro; I even shook his hand. We had dinner with him in Havana.”

18

It was probably Castro who urged President Dos Santos of Angola to send his army into Congo.

19

Kabila’s coalition grew. After Zimbabwe and Angola, Namibia joined in as well. Northern allies were found in Sudan, Chad, and Libya, each of which had its own reasons for preventing Kabila’s fall. Sudan offered its services because of a perennial conflict with Uganda over its support for rebels in southern Sudan. Libya provided a few planes in order to break out of its international isolation. Chad sent two thousand soldiers as a gesture of solidarity with Sudan and Libya. In the end, Kabila had a seven-nation army at his disposal: in addition to his own forces, there were troops from three countries to the north and three to the south. This was the coalition that stood up to the three countries from the east and operated behind the blind of the RCD: Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi, with Rwanda as leading player and America’s undisputed favorite. Once again, Congo’s central location played a crucial role in the course of history. The armies now facing off were large: Kabila’s coalition had approximately eighty-five thousand troops, the rebels some fifty-five thousand.

20

This impressive military presence led to a complete stalemate. Western Congo was soon back in Kabila’s hands, but the east was still held by the RCD. There was no real front, only clearly defined zones, often divided by a very broad stretch of no-man’s-land. Kabila’s authority extended only as far as Bas-Congo, Bandundu, western Kasai, and a large part of Katanga; Kigali and Kampala controlled northern Katanga, North and South Kivu, Maniema, and Orientale province. When Chad withdrew from Équateur in 1998, that part of the country fell into rebel hands as well. The occupying force this time, however, was not the RCD but a new rebel army supported exclusively by Uganda: the Mouvement pour la Libération du Congo (MLC). Its commander was Jean-Pierre Bemba, son of the wealthiest businessman of the Mobutu era. His troops consisted largely of veterans of the Division Spéciale Présidentielle (DSP), Mobutu’s remorseless private army.

21

Rwanda’s second invasion was intended to be a repeat of that in 1996, but this was not the case. Due in part to the sentiments of the local population, the situation in Congo had become intractable. If the AFDL had once been welcomed as a liberation army, the RCD was seen right away as an invasionary force. In a city like Goma, Kabila was still extremely popular. When Wamba dia Wamba tried to recruit local boys for his RCD, Jeanine Mukanirwa mobilized her influential association of rural women. She had helped found the women’s movement in Kivu at the end of the Mobutu era. “There were five thousand of us women. Wamba dia Wamba came by to try and win us over for his rebellion. He called it a war of rectification, but we knew that Rwanda was behind it. We said: ‘In 1996 you people took away our children to fight. Now you come to take the rest of them to fight against their own brothers. Your war has no justification!’ Yes, we women were courageous back then.”

22