Conquistadors of the Useless (56 page)

Read Conquistadors of the Useless Online

Authors: Geoffrey Sutton Lionel Terray David Roberts

Then I saw Soubis begin to come down towards me, looking rather stupefied. I shouted to him to wait for me. Soon I was beside him. He had not realised what had just taken place. At the moment of my fall he was not belaying me, but peacefully arranging the strap of one of his crampons. He had been very surprised when the bundle of rope which he had put down in front of him had suddenly reeled off at top speed, though he had not guessed the cause. We then realised the lucky chance which had prevented us from making âthe great leap' together. At the moment of my slip the second party had just fitted the thin âMenaklon' line to a stake that had been firmly planted in the snow. Only this thin line had stopped my fall and prevented Soubis from being dragged off behind me.

Surely luck had been with us in our accident, nevertheless, my elbow had been severely sprained and my arm was horribly painful. I was deeply annoyed: I now knew that I would never get to the top of Huntington and this seemed to me most unfair. I had worked for months to have those unparalleled minutes of joy and excitement, and now I was to be cast aside like a useless beast.

The descent was done slowly, but with the help of the fixed ropes I was able to move reasonably well.

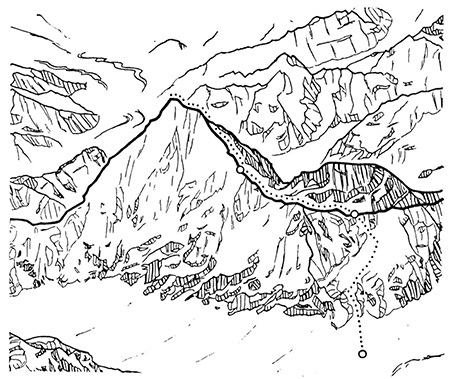

For me the accident was catastrophic, but the expedition was not going to stop for that. By nine the next morning four men had already reached the scene of my fall and it seemed they had a good chance of getting to the summit. In order to find snow, they tried to pass along close to the edge of the arête, but they had scarcely begun to climb the first point of the âlace' when a large piece of cornice crumbled into the Ruth Glacier: another few inches and Gicquel would have gone with it.

The wind blew and it was very cold. The arête was interrupted endlessly by short but vertical walls of ice, and progress was extremely slow.

Soon Martinetti complained that the ophthalmia which he had contracted two days earlier was worsening rapidly. His sight was almost gone and he suffered intolerably. Once again we were forced to descend, but this time we had gained only a few score yards and the party's morale fell hopelessly.

At Camp One that evening we held a council of war. After a brief discussion we argued that the âlace' had turned out much more difficult than we had thought, and because the last step was not at all an easy walk the final stage on Huntington would still require a few more days. To avoid losing time in coming and going along the crests, we decided to set up a second camp at the foot of the Second Step.

At an early hour the six fit men descended to Base Camp to get more provisions and equipment. Unfortunately, a storm blew up in the afternoon and they could not climb back the same day.

Martinetti and I remained alone in the cave â a sad couple: he completely blind, me with a crippled arm. It was with great difficulty that I did the cooking and helped my comrade who could do practically nothing for himself.

Outside the snow fell ceaselessly: our comrades at Base Camp (with whom we talked by radio) told us that on the Ruth Glacier more than a metre had fallen in twenty-four hours. Thus we remained blocked for two long days. To pass the time I tried to read, but I did not succeed. I was very depressed and very uneasy. I had read somewhere that big storms in this massif can last for eight or ten days. Now we had almost no provisions or fuel, and without doubt we were going to be forced in the midst of the storm to descend the evil slope that separated us from base camp. With almost two metres of new snow that would be ideal terrain for an avalanche.

During the twenty-five years that I have climbed among all the mountains of the world I had seen too many such avalanches begin beside me, or even over me, sometimes in the most unpredictable places. At the very idea of becoming involved on that slope I felt an animal-like fear.

At dawn on the third day the storm had ceased but the sky was still very cloudy and the temperature rose. We had to descend quickly before the fog came back and the snow warmed up. Martinetti had practically regained his sight and I was able to use my arm a little. In the first couloir the snow had slid and we went quite quickly, but lower down an exhausting struggle began. We plunged in up to our bellies, and sometimes to the waist; the fog surrounded us and we could see only for a few yards; many landmarks had disappeared and it was very difficult not to lose the proper route. Moreover, the fear of seeing the whole slope move and of feeling oneself carried away helplessly plunged us into miserable anxiety. Luckily, the snow remained very cold, which lessened the danger a great deal. Eventually we reached the last couloir: here the new snow had already slipped off and we had only to let ourselves down the fixed ropes. Soon we were able to greet our comrades.

On the next day, at dawn, the wind was very violent, but the sky was limpid blue; my seven companions climbed up again to Camp One with heavy loads of provisions and equipment. Their plan was to send a party out on to the arête, and on the same day to pitch camp two, from which they would be able to launch the final assault on the summit.

Throughout the morning, very depressed, I watched my friends ascending. In all my life I have rarely felt so alone and unhappy: I had not even the courage to prepare a meal. During the night I scarcely slept, but in the morning I had reached a decision: I would rejoin my comrades and try to follow them to the summit. Certainly, my arm still gave me great pain, but by using the Jumar with my left hand, I should be able to make progress.

At seven I made contact with Soubis and asked him to wait for me, which he agreed to do with pleasure. I took quite a long time getting ready. The track was still good but I was heavily laden and I made quite slow progress. The bergschrund that barred the upper part of the route held me up for a long time as it was very wide and overhanging. With only one arm I was not able to drag myself up with the jumar. Finally, thanks to an etrier, I succeeded in getting through though only after a desperate effort.

It was after 5 p.m. when I emerged upon the arête Soubis and Gendre welcomed me with friendly smiles, which gave me great comfort. I was exhausted and hungry, and I simply had to regain my strength before going on.

While I was eating, my two friends told me that after many hours of step-cutting Gicquel and Martinetti had succeeded in reaching the foot of the Fourth Step, while Batkin, Bernezat and Sarthou had been able to set up a rudimentary but adequate camp two.

We started off again at 6 p.m. but the weather had changed: it was snowing a little and the wind was blowing strongly, continually raising enormous and blinding swirls. Knowing the instability of the weather in this massif, we went on nevertheless. I had recovered my morale and energy and thanks to Soubis, who helped me a lot, I was able to haul myself up the fixed ropes without slowing our progress too much.

The higher we rose the greater became the intensity of the storm and when we reached Camp Two at 11 p.m. we were in the midst of a real hurricane.

While six men packed into a four man âMakalu' tent as best they could, Soubis and I shut ourselves up in a minute bivouac tent which was soon almost completely buried under the snow. We spent a heroic and splendid night struggling to feed ourselves and get a little rest.

In the morning we had to surrender to facts: the storm raged on and it was impossible for all eight of us to remain there waiting for good weather. We had not enough room, nor provisions, nor fuel. I decided that Batkin and Sarthou, who until then had done most of the less spectacular jobs, should remain so as to try and reach the summit at the first clearance. Then we started down the route to Camp One. The storm was diabolical, but we were now so used to the cold and the wind that this struggle with the elements seemed to us like an exciting game.

The next day (the 25th of May), when we emerged from our cave, the weather was very moderate; the wind had almost fallen and the snow had stopped; on the other hand, Huntington was completely hidden by heavy clouds.

At 10 a.m. when we resumed radio contact with our two comrades, we learned with surprise that they had set out very early and that, despite the wind, they had just reached the foot of the Fourth Step.

At noon, further contact told us that Batkin and Sarthou had surmounted a last difficult wall and were about to attack the terminal ridge. The wind, snow and fog hindered them a great deal, but their morale was steely and they were fully determined to reach the summit at all costs.

We lavished them with encouragement but also with advice to go carefully. Following their progress by radio was wildly enthralling; we were all in a state of extreme excitement. Eventually, at 4.30 p.m. Sarthou's voice, trembling with emotion, told us that for several minutes Batkin and himself had been standing on the top of Mount Huntington.

We jumped for joy and hugged one another like brothers. We experienced one of those moments of simple happiness which show their real meaning in mountaineering. I begged my two comrades to descend carefully and every two hours I made contact with them. The two men were tired and the wind had so filled their tracks that they had great difficulty in finding their steps again. In such conditions the descent was very slow and difficult. And they did not regain the camp until well after midnight.

Despite systematically equipping the route with fixed ropes, it still required twenty-three hours of almost uninterrupted effort to complete the final day of climbing on Mount Huntington. I think that in its very simplicity this figure shows very well how arduous and difficult the struggle had been.

Gendre, Martinetti, Gicquel, Bernezat, Soubis and I set out at 2.30 a.m. The weather was extremely cloudy, but the wind had fallen entirely and the temperature had eased a great deal.

At six we passed Camp Two, where our two comrades wished us luck. Then the climb was resumed at top speed. Fortunately, the tracks had not been filled up and I had become so used to using my left arm that I was able almost to keep up with the first two ropes.

At last we attacked the elegant âlace' and I understood why so much time had been taken in overcoming it, we continually ran up against walls of ice that were quite short but vertical or even overhanging.

Now and again we exchanged yodels and shouts of delight. After so many difficult and dark days we had a marvellous feeling of liberation. We felt strong and light, and this ascent from crest to crest seemed like a triumphant gallop.

Eventually at 11.30 we were all together on the narrow summit. Unfortunately, the sky remained very cloudy and we had not a single glimpse of the great mountains that surrounded us. Delight showed, on every face: we were all shouting and singing, and it was in a festive atmosphere that we went through the traditional rites that mark the conquest of a peak.

But soon we had to start the descent. Suddenly I felt sad and distressed. I know, certainly, that a mountaineering victory is only a gesture in space, and for me, after the Himalayan and Andean peaks, Huntington was only another summit. Nevertheless, it was sad to leave that crest!

On this proud and beautiful mountain we had spent many ardent and noble hours in brotherhood. We had ceased for several days to be slaves and had truly lived as men. To return to slavery was hard â¦

Lionel Terray's Climbs and Expeditions, and other Achievements

Symbols:

§ first ascent of mountain or route

+ expedition doctor

1933

Chamonix area.

First alpine season. Trip to Couvercle Hut with guide. Ascent of Aiguillette d'Argentière with an older cousin who was working at the Ecole Militaire de Haute Montagne. They also did Clochetons de Planpraz, the south-east face of the Brévent, the Grands Charmoz and the Petite Aiguille Verte.

1934

Vercors.

Dent Gerard in Trois Pucelles by the âGrange Gully'. Climbed with his friend Georgette and five others (one of whom was more experienced). This developed into a minor epic with Terray soloing the âSandwich Crack' to assist the leader hoist his second up the âDalloz Crack'. Later Terray tried the route again with Michel Chevallier but failed. Chamonix area Second guided alpine season doing classic easy routes.

1935

Won prizes in regional ski competitions in Dauphine

Aiguille du Grépon.

Traverse via Mummery Crack, with Alain Schmit and a pushy guide who hoisted them up the climb â an efficient demonstration of brutal guiding.

1937

Won first ski championship. Reclimbed Grange Gully (Trois Pucelles) with a schoolmaster (G.H.M. member) in better style.

1939

Does well in national skiing championships in the Pyrenees and another competition in Provence during illicit absence from his school in Chamonix. Expelled, having already been moved from two other schools after similar incidents. Took part in further ski contests and earned some money as a ski instructor.

1940

Aiguille du Moine.

Ascent of south-west ridge with Robert Michon (G.H.M.), an ex-soldier who sought him out after the end of hostilities in the north. This climb re-ignited Terray's climbing interests after years of skiing. They went on to do a series of classic routes during the summer including the north ridge of the Chardonnet and the Cardinal.

1941

Third in national ski championships.

Joined âJeunesse et Montagne' â a cadre of young outdoor instructors (with a military and mountain flavour) based at Annecy. In this Terray first met the Marseilles climber Gaston Rébuffat who had ambitious designs on great north faces. Both were later seconded to a climbing instruction unit at Montenvers commanded by André Tournier.

Dent du Requin

(Mayer/Dibona),

Aig. du Grépon

(east face) with Gaston Rébuffat.

1942

Married Marianne Perrollaz (who he met at a ski championship), and rented a farm in Les Houches. Gaston Rébuffat worked as their farmhand for a period.

Aiguille Purtscheller.

West face § plus other climbs with Gaston Rébuffat (6th May).

Col du Caiman.

North flank §, with descent by Pointe Lépiney and down the south ridge of the Fou, with Gaston Rébuffat (26th Aug) â an epic and (for Terray) inspirational ascent, with difficult glacier work and an ice runnel to the col (c. Scottish 4).

Joins Group Haute Montagne.

1943

Aiguille du Peigne.

New line on west face of summit tower § (left of the Lépiney Crack) with René Ferlet (2nd Aug). Terray later had a close escape on this climb when he dropped his equipment at a critical point.

Aiguille des Pèlerins.

West ridge § with Ãduoard Frendo and Gaston Rébuffat (10th Oct).

1944

Meets Louis Lachenal in Annecy.

Paine de Sucre.

East-north-east spur § (2nd Aug) with Gaston Rébuffat.

Aiguille des Pèlerins.

North face â L/H route § (10th Aug) with Gaston Rébuffat. Later to become an important winter climb (§ Rouse and Carrington, Feb. 1975).

Pointe Chevalier.

East face § (11th Aug) with Gaston Rébuffat.

Following Liberation (August) Terray joined Compagnie Stéphane (ex Maquis) newly incorporated into the Chassuers Alpins. In this largely-independant unit Terray saw eight months of army service, with action on the Italian frontier near the Dauphiné.

Col de Peuterey.

North face § as a new approach to the

Peuterey Ridge

with Gaston Rébuffat and the brothers Gerard and Maurice Herzog (15th Sept).

1945

Transferred by Captain Stéphane to Ecole Militaire de Haute Montagne, Chamonix.

Petits Dru.

North face (via Allain Crack â HVS) with Jacques Oudot (15th Aug).

Aiguille Verte.

Couturier Couloir with J.P.Payot, followed by Lachenal and Lenoir.

Aiguille du Moine.

East face (Aureille/Feutren), second ascent with Louis Lachenal.

Qualifies as a guide and is accepted into Chamonix Guides Company.

Aiguille des Pèlerins.

Grutter Ridge â difficult step direct § with Jo Marillac.

Aiguille Noire.

South ridge with Jo Marillac.

1946

Les Droites.

North spur with Louis Lachenal, Andre Contamine and Pierre Leroux in eight hours (one hour down to Couvercle) (4th Aug).

Grandes Jorasses.

Early repeat of the Walker Spur with Louis Lachenal (10-11th Aug) with a variant trending into the Central Couloir § from above the Grey Tower.

Argentine.

Second ascent of Grand Dièdre with Tomy Girard.

Bietschhorn.

South-east ridge and down north ridge with Louis Lachenal.

Matterhorn.

Furggen ridge with Lachenal, Tomy Girard and René Dittert.

1947

Aiguille Verte.

Nant Blanc face (Chariet/Platenov) with Louis Lachenal (31st May).

Eiger.

North Face (1938 Route). A publicised second ascent with Louis Lachenal â bivouacs in Swallow's Nest and at the top of the Ramp (14-16th July).

Aiguille de Blaitière.

West face (Allain/Fix). Second ascent with Louis Lachenal, Louis Pez and Joseph Simpson (20th Sept).

Becomes an Instructor at I'Ecole Nationale d'Alpinisme (Director: Jean Franco).

1948

Moves to Quebec to run a hotel ski school, teach instructors and coach the State team. â a comparatively lucrative posting lasting from Nov 1947 to Spring 1949.

1949

Mont Blanc.

Brenva Face (Route Major) with Jean Gourdain (27th July).

Grand Capucin.

(1924 Route) with Tom de Lepiney.

Grandes Jorasses.

Tronchey Arête second ascent with Jean Gourdain (31st July-1st Aug).

Piz Badile

north-east face with Louis Lachenal in seven and a half hours (9th Aug).

1950

Annapurna.

§ April-June via the north face â the first 8,000-metre peak to be climbed. Maurice Herzog (leader), Louis Lachenal, Lionel Terray, Gaston Rébuffat, Jean Couzy, Marcel Schatz, Jacques Oudot+, Francis de Noyelle, Marcel Ichac with Ang Tharkay (sirdar), Pansy, Sarki, Adjiba, Aila, Dawa Thondup, Phu Tharkay, Ang Dawa and others. After investigating several possibilities on

Dhaulagiri

during April, the party moved to Annapurna. After attempting the north-west spur they took the northern glacier route. Herzog and Lachenal reached the summit (3rd June, without oxygen) but mishaps turned the descent into a survival struggle involving Terray and Rébuffat (support team). Herzog and Lachenal were severely frostbitten. Annapurna by Maurice Herzog (Cape, London, 1952; Dutton, New York, 1953); Camets du Vertiges by Louis Lachenal (Guerin, Chamonix, 1994).

Aiguille Noire.

September â a west face attempt was aborted after Terray's companion, Francis Aubert, was killed whilst descending (unroped) below the Col de I'lnnominata.

1951

Aiguille Noire.

West face early repeat with Raymond Emeric.

1952

FitzRoy

(or Chalten).

[1]

§ René Ferlet (leader), Marc Azéma, Guido Magnone, Lionel Terray, Louis Dépasse, Francisco Ibañez (liason officer), Louis Lliboutry, Georges Strouvé and Jacques Poincenot. There was an early tragedy when Poincenot, a talented rock climber, drowned during a hazardous river crossing (rumours that this might not have been the true cause of his death appear to be apocryphal). From Camp Three (an elaborate snow cave) Magnone and Terray tackled the south-east buttress utilizing several hundred feet of fixed rope and 118 pitons or wedges. There followed a final two-day summit push. Complex and difficult, the climb has proved less popular than the 1968 Californian route, or the 1965 Super-Couloir. The Conquest of FitzRoy by M.A. Azema (Deutsch, London, 1957).

Aconcagua.

The FitzRoy party then tackled this peak but (as most were not acclimatised), only Terray and Ibañez reached the summit, in the process assessing the south-east ridge and south face (climbed in 1954 by another French expedition).

Note: Ibañez (presumably briefed by Terray) mounted and led the 1954 Argentinian Dhaulagiri expedition. He returned from his summit push frostbitten but failed to withdraw quickly for treatment. He died of gangrene after his feet were amputated in Kathmandu.

Nevado Hauntsan

§ and

Nevado Pongos

§ (Cordillera Blanca) by Lionel Terray with his clients and friends Tom De Booy and Kees Egeler. The untrodden Andes by C.G.Egeler and T De Booy (Faber, London 1954).

Mont Blanc

,

R/H Freney Pillar.

With Godfrey Francis and Geoffrey Sutton.

Film-making:

Terray shot his first movie footage in the Andes and then made the film

La Conquete du Hauntsán

(with J.J.Languepin). He also made

La Grande Descente du Mont Blanc

(with Georges Strouvé and Pierre Tairraz). Both films won prizes at the Trento Festival.

1954

Makalu.

August-October: a reconnaissance expedition (to identify the correct route and try out new equipment) with Jean Franco (leader), Lionel Terray, Jean Couzy, Jean Rivolier, Pierre Leroux and Jean Bouvier. Makalu La § was reached by Leroux and Bouvier (15th Oct) and probes made on the north face to c.7,800 metres.

Kangchungste

§ (Makalu 2) was climbed by Franco, Terray, Gyaltsen Norbu and Pa Norbu (22nd Oct) and

Chomo Lonzo

§ by Terray and Couzy (c.30th Oct) â both ascents were made with their highly effective new oxygen equipment. Makalu by Jean Franco (Jonathan Cape, London, 1957).

1955

Mont Blanc Massif.

Louis Lachenal dies in a ski accident â he fell into a crevasse whilst descending from the Vallée Blanche to the Mer de Glace.

Makalu.

§ April-May: first, second and third ascents by an expedition led by Jean Franco, with Lionel Terray, Jean Couzy, Guido Magnone, Pierre Leroux, Jean Bouvier, Serge Coupé, André Vialatte, André Lapras+, Michel Latreille, Pierre Bordet, Gyaltsen Norbu (sirdar), Aila, Panzy, Mingma Tenzing, Ang Bao, Ang Tsering and others. Ascents were made by Couzy and Terray (15th May), Magnone, Franco and Gyaltsen Norbu (16th May), and Bouvier, Coupé, Leroux and Vialette (17th May). Makalu by Jean Franco (Jonathan Cape, London, 1957)

1956

Pic Soray

§ (Cordillera Vilcabamba) â by the north face;

Nevado Salcantay

â second ascent and

Nevado Veronica

§ (Cordillera Urubamba), by Lionel Terray, Kees Egeler, Tom De Booy, Hans Dijkhout and Raymond Jenny.

Chacraraju

§ (Cordillera Blanca) First ascent (by north face, with much fixed rope) by Lionel Terray (leader), Maurice Davaille, Claude Gaudin, Raymond Jenny, Robert Sennelier and Pierre Souriac (31st July). Also involved was Maurice Martin. The same six also climbed

Taulliraju

§ (by the north-east ridge on 13 Aug). Both routes, with hard ice climbing and tough rock pitches, are amongst the most difficult in the Andes.

1957

Mont Blanc.

January: rescue bid to save the students Francois Henry and Jean Vincendon (beleaguered during a traverse of Mont Blanc begun on 23rd Dec, 1956). They had been placed by rescuers in a crashed helicopter on the Grand Plateau. Terray and others â all unofficial rescuers (approaching from the Grands Mulets on foot) were forced to retreat (1st Jan). Further helicopter rescue bids failed and efforts were officially ended in good weather conditions on (3rd Jan) because of fear of further crashes. Terray and others were highly critical of the failure of the Chamonix Mountain Rescue to initiate an effort on foot when the alarm was first raised on 26th Dec. âThe Tragedy on Mont Blanc' by Rene Dittert (Mountain World 1958/59, pp.9-19).

Wetterhorn.

North-west face with Kees Egeler and Tom De Booy.

Eiger.

Rescue bid on the north face to reach the injured Claudio Corti and Stefano Longhi, marooned in different positions high on the face. Two other climbers who had disappeared were later found to have been avalanched whilst descending the west face. A multi-national team, directed by Robert Seiler, Eric Friedli and Ludwig Gramminger, set up a winch/cable system on the summit. Alfred Hellepart recovered Corti, but Terray's attempt to reach Longhi was foiled when the cable jammed. Terray with Gramminger, Friedli, Mauri, Cassin, Schlunegger, De Booy and others then lowered Corti down the complex west ridge.

Grosshorn

and

Triolet

climbed by their north faces with Tom de Booy (two of several classic Alpine ice faces which Terray did with his Dutch clients De Booy and Egeler).

1958

Pointe Adolphe Rey.

East ridge direct § with Robert Guillaume.

Grand Capucin

and other locations: filming Marcel Ichac's

Le Etoiles de Midi

.

Jean Couzy killed in rock fall on Crete de Bergers, south-west face.

1959