Conquistadors of the Useless (54 page)

Read Conquistadors of the Useless Online

Authors: Geoffrey Sutton Lionel Terray David Roberts

It would be both long and boring to analyse the reasons for this failure. There were a number of contributing factors, and every member of the team would probably emphasise one or another according to his temperament. Personally, I think one can only say that our ambition exceeded our abilities. Climbing is before everything else a gamble, even on the Himalayan scale, and if it lost its element of hazard it would lose its own nature. âIt is obvious that the risks and doubts must increase in proportion to the technical difficulties', as Lucien Devies has said. We had deliberately chosen difficulty on a gigantic scale, thereby reducing our own chances. Even before setting out we had reckoned that the odds on getting up Jannu were no better than thirty per cent. We had gambled and lost. Nothing could be more natural.

The level and continuity of the difficulties, the length and complexity of the route, the state of the weather and the element of luck all combined to take up too much time. When we eventually reached our highest point the season was almost over and we were too short of material necessities to finish out with a reasonable margin of safety. The mountain had had the last word, though there had not been much in it. With a slightly bigger organisation and a little more luck the spirit of man would once again have triumphed over the insensate forces of nature.

There was no disagreement when we got back to Paris: we would just have to try again. The experience we had now acquired should suffice to tip the scales in our favour. Our enthusiasm persuaded the Himalayan Committee to arrange for a new attempt in 1961, but various circumstances combined to delay it until 1962. Jean Franco felt that he was beginning to get old for this kind of thing, and at his request the leadership was entrusted to me, a heavy responsibility which I only accepted after a good deal of hesitation.

In a few days' time I shall be forty years old. Twenty years of action on the mountains of the world have left me with more energy and enthusiasm than the majority of my younger companions, yet I am no longer altogether the same person who once rode roughshod over men and the forces of nature to victory on the Walker, the Eiger, the Fitzroy and Chacraraju. So many years of trial and danger change a man in spite of himself.

Shortly after our return from Jannu I was crossing the Fresnay glacier with a client when we were surprised by an avalanche of séracs. My companion was killed and I was buried under fifteen feet of ice.

At that moment it seemed as though the insolent luck which had hitherto walked by my side had abandoned me at last, but in fact, by one of the most amazing miracles in the history of mountaineering, I emerged without a scratch. Imprisoned under a block of ice in the bottom of a crevasse, I managed by a series of contortions to reach a knife which I had by sheer chance left in my pocket. With its aid I was able to reach a cavity in the debris which, once again, had formed close to me by the merest luck. With an ice piton and my peg hammer I then carved out a gallery towards the light. Five hours later I reached the fresh air. This stay in the antechambers of death, where yet another companion was lost at my side, ripened me more than ten years of successful adventures.

In every adventure, whatever my nominal capacity, I have marched with the van. On expeditions or in the Alps, I have accepted every risk and responsibility with a tranquil mind. If I have sometimes led others into danger I have never hesitated to stand at their side. Today my willpower is no longer quite so inflexible, the limits of my courage not so far out. In the assault on the most redoubtable bastion ever invested by a group of mountaineers will I still be a captain leading his shock troops in the last charge, or will I have changed into a general who waits in fear behind the lines while his men advance into action?

And after Jannu, what? Will there be anything left to satisfy man's hunger for transcendence?

There can be no doubt that others will tackle peaks less high, but harder still. When the last summit has been climbed, as happened yesterday in the Alps and only recently in the Andes, it will be the turn of the ridges and faces. Even in the era of aviation there is no sign of any limitation yet to the scope for the best climbers of their day.

My own scope must now go back down the scale. My strength and my courage will not cease to diminish. It will not be long before the Alps once again become the terrible mountains of my youth, and if truly no stone, no tower of ice, no crevasse lies somewhere in wait for me, the day will come when, old and tired, I find peace among the animals and flowers. The wheel will have turned full circle: I will be at last the simple peasant that once, as a child, I dreamed of becoming.

1.

Translator's note.

The height of this mountain is disputed.

[back]

2.

Translator's note.

Then equivalent to approximately £100.

[back]

3.

Translator's note.

Dunes of snow formed by the wind.

[back]

4.

Translator's note.

Gosainthan, which is in Tibetan Territory.

[back]

5.

Translator's note.

Climbed in 1962 by a party including Terray.

[back]

6.

Translator's note

. The author refers to the New Year rescue attempts on Mont Blanc.

[back]

7.

Translator's note.

It was climbed by the 1962 party led by Terray.

[back]

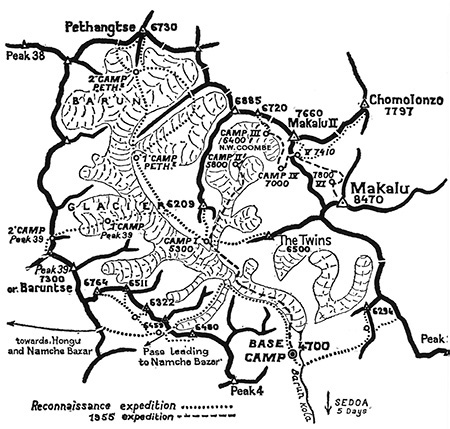

Sketch-map of south-western Nepal. The dotted line shows the route taken by the expedition to Makalu. (Heights are given in metres.)

The Makalu massif. (Heights are given in metres.)

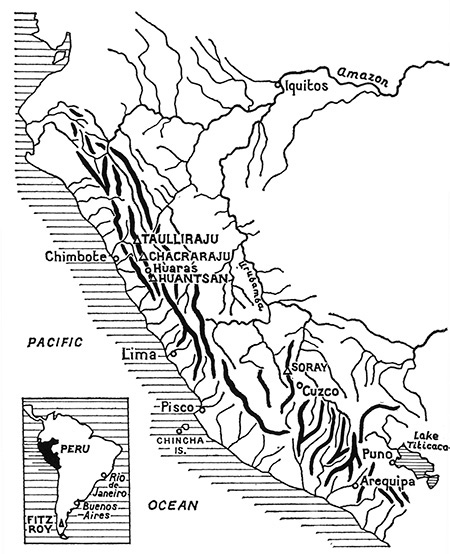

Map of Peru.

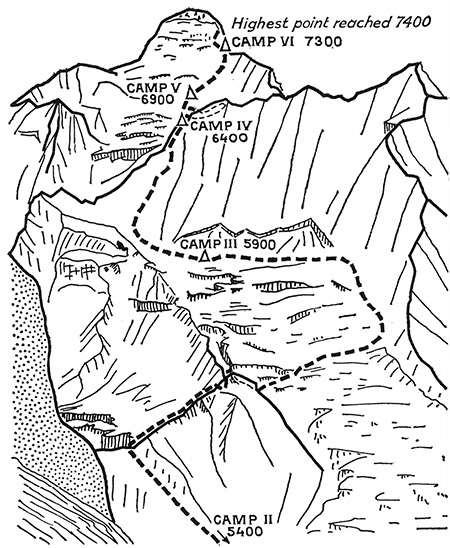

A sketch of Jannu from the south-east, showing the route taken on the first attempt. (Heights are given in metres.)

Towards the end of this book it must have seemed to the reader that my personality was changing, that the springs of my energy were gradually drying up as a result of too-numerous adventures and incessant activity, that the philosopher was gaining the upper hand over the man of action. The tone of the last pages gives an impression that, in accepting leadership of the second Jannu expedition, I was thinking of it as a sort of swan song to be followed by progressive retirement into a more peaceful way of life.

Nothing could have been farther from the truth. 1962 was in fact the most active and important year of my whole career.

No sooner had I finished writing

Conquistadors of the Useless

in July than I began the guiding season. In September I went to Paris to undertake the enormous administrative burden of organising a large-scale expedition. Everything was going well when, in November, a ledge gave way under me while climbing on the Saussois (a limestone crag some hundred and twenty miles south-east of Paris) and I fell thirty feet, breaking six ribs and perforating the pleura. The doctors at the hospital condemned me to bed for a month. It seemed that if I was lucky I might be able to go with the Jannu expedition as far as base camp, but that any idea of taking part in the assault was out of the question.

No doubt this was a correct prognosis for a typical social security subscriber, but a guide's life is not like that. Three days later I spent four hours dictating letters, and five days after that I left hospital altogether, against all the best advice, to take up my task again in spite of a good deal of pain.

Despite the delay caused by this accident, the expedition was ready on schedule. Bigger and better equipped than its predecessor, it set out for the mountain at the beginning of March. Base Camp was pitched on the 19th. The team of ten climbers and thirty picked Sherpas was technically very strong, and armed with the previous year's experience they carried out the attack with such address that Camp Six was set up by April 18th, a full fortnight in advance of our most optimistic predictions.

At first I was so fatigued from the accident and the weeks of overwork that I could only co-ordinate and direct, but as the days went by I began to feel better. As soon as Camp Three had been pitched I began climbing again, and by April 15th I was once more happily at the front of one of the assault teams. Two days later I led and fixed ropes up a large part of the steep ice face between Camps Five and Six. On the 26th, although my oxygen apparatus was not working properly, I was able to lead for most of the barrier of rock slabs that had stopped us the year before. Twenty-four hours later four of my team-mates finally reached the summit which so many Himalayan mountaineers had thought inaccessible, and in the next couple of days seven other Sherpa and French climbers, including myself, stood on its ideally pure point.

We got back to France at the beginning of June, and less than a month later I was on my way to Peru. This time our objective was the redoubtable east peak of Chacraraju, a dream I had been cherishing for six years. From the summit of the west peak in 1956, which is some three hundred feet higher, we had been able to pick out every detail of this apparently unclimbable arrowhead of rock and ice. So formidable did it seem that after our success on the higher summit we abandoned the idea of attempting it, and fell back instead upon the more modest Taulliraju.

Shortly afterwards I was to write: âThe east peak of Chacraraju will call for the undivided attention of an extremely strong party.' This proved to be no exaggeration, for subsequently several expeditions of various nationalities which had gone to Peru with the mountain as their express object retired discomfited at the mere sight of it. Our group, of which the leadership had been confided to me, was organised by Claude Maillard and contained several highly expert climbers, of whom the best-known was perhaps Guido Magnone. By virtue of my previous Andean experience, and the fact that I was still in excellent trim from the Jannu expedition, I was able to remain in the forefront of operations for three weeks without intermission. Our route up the east face and north-east ridge was both severe and sustained. The last couple of thousand feet in particular were extreme, mainly on ice but also occasionally on rock, and this at an altitude where even the fittest of men are somewhat handicapped. Naturally, it was a very slow business, and on certain days the party in front would not succeed in surmounting two hundred feet. The route was in fact so tortuous that we had to fix six and a half thousand feet of rope to climb a vertical height of only two and a half thousand. Lengthy and exhausting as the task was, it brought its reward on 8th August when five of us attained the delicate ice fretwork of the summit. The following day, thanks to our fixed ropes, I visited it a second time with our film photographer, Jean-Jacques Languepin, and four more of the party reached it within the next twenty-four hours.

1962 held yet another adventure in store. After ten years of groundwork my Dutch friends Egeler and De Booy had succeeded in getting afoot an expedition to the Himalayas, and by mid-September I was on my way to join them in Nepal. As always, their aims were both sporting and scientific, the climbing group consisting of five Dutch mountaineers led by myself. Our objective was Nilgiri, a fine mountain of 23,950 feet close to Annapurna, whence we had seen it in 1950.

I caught up with them at the end of September, after a long forced march, at the last village before the mountain. After some rapid reconnaissances we decided to attack the north face. This was consistently steep and looked difficult in its central part, but it was sheltered from the prevailing winds and relatively safe from objective hazards. Some serious rock obstacles were swiftly overcome, and Camp Two was installed on a terrace just under 20,000 feet. Our lack of Sherpas obliged all of us to undertake some heavy portering work to stock the camp as quickly as possible. Above, our way lay up and across a very steep ice slope, an obstacle it took us no less than six days to surmount and equip with fixed ropes despite its mere 1,200 feet. Camp Three was eventually placed on the final ridge at around 21,300 feet. The last lap offered no particular difficulty, and we climbed it in a little over half a day. It was on the 26th October, a day of icy gales, that the three brothers Van Lookeren Campagne and the Sherpa Wongdi stood with me on the summit, gazing across at the north face of Annapurna.

The first ascent of Nilgiri was not in the same class as those of Jannu and Chacraraju East, but it was quite serious enough for all that; and it was the first time in the history of mountaineering that one man had led three major expeditions to success in the course of one year, in three distinct ranges and on two continents.