Consciousness Beyond Life: The Science of the Near-Death Experience (13 page)

Read Consciousness Beyond Life: The Science of the Near-Death Experience Online

Authors: Pim van Lommel

The percentages of change in the Dutch study are significantly lower compared to those in the retrospective studies by Ring and Sutherland, among others, which cite percentages of 80 to 100 percent for the same changes. The most likely explanation is the much longer passage of time between the NDE and the interview (typically more than twenty years) and the inclusion of NDErs who had come forward voluntarily, which resulted in much deeper experiences than those reported by the patients in the prospective Dutch study. In our study, many people with a deep or very deep NDE died shortly after their cardiac arrest so that they could not be included in the later interviews about change. Neither does our table reveal the number of people who had no fear of death or who already believed in an afterlife prior to their NDE.

32

Spiritual growth is the sole purpose of our life here on earth.

—E

LISABETH

K

ÜBLER

-R

OSS

In summary, there is no such thing as a classic near-death experience or a classic way of dealing with it. The often difficult and painful process of coming to terms with an NDE and the resulting positive changes depend on the depth of the NDE, personality structure, cultural background, and, above all, social factors. The latter includes the sometimes positive but usually negative or skeptical response of friends, family, and health care practitioners, which often prevents communication about the NDE and thus significantly slows or halts the process of coming to terms with the experience. As a result, the integration process suffers a serious setback while psychological problems eclipse a positive and loving attitude to life. The process of change cannot get under way until people have shared their experience with others and feel that both they and their NDE are accepted. This in turn facilitates the integration of the subsequent changes. Advising people to write down their NDE might boost and perhaps accelerate the process of change. It may help them find the right words for the experience and perhaps also write to others about it.

What if you slept? And what if, in your sleep, you dreamed? And what if, in your dream, you went to heaven and there plucked a strange and beautiful flower? And what if, when you awoke, you had that flower in your hand? Ah, what then?

—S

AMUEL

T

AYLOR

C

OLERIDGE

Children who have a near-death experience remember the same typical elements as adults; but how is this possible when children have never heard of near-death experience or, in some cases, have not even learned how to read yet? When it comes to the veracity of NDE reports, some people continue to believe that NDErs are simply telling a story based on prior knowledge of the phenomenon or on religious expectations about the content of an NDE. But this does not apply to young and spontaneous children. It seems inconceivable that children without any prior knowledge could fabricate a story that is entirely consistent with the NDE reports of adults. Young and uninhibited, children will talk about what really happened to them. In this chapter we look at the near-death experiences of children because it is unlikely that children’s NDE reports are the result of any outside influence.

When I was five years old I contracted meningitis and fell into a coma. “I died” and drifted in a safe and black void where I felt no fear and no pain. I felt at home in this place…. I saw a little girl of about ten years old. I sensed that she recognized me. We hugged and then she told me, “I’m your sister. I died a month after I was born. I was named after your grandmother. Our parents called me Rietje for short.” She kissed me, and I felt her warmth and love. “You must go now,” she said…. In a flash I was back in my body. I opened my eyes and saw the happy and relieved looks on my parents’ faces. When I told them about my experience, they initially dismissed it as a dream…. I made a drawing of my angel sister who had welcomed me and repeated everything she’d told me. My parents were so shocked that they panicked. They got up and left the room. After a while they returned. They confirmed that they had indeed lost a daughter called Rietje. She had died of poisoning about a year before I was born. They had decided not to tell me and my brother until we were old enough to understand the meaning of life and death.

Scientific Research into NDE in Childhood

Scientific research shows that children can indeed have an NDE. Pediatrician Melvin Morse carried out the first systematic study of NDEs in childhood at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

1

Over a ten-year period he interviewed 121 children who had been critically ill; 3 of them reported a hallucination, but none had actually had an NDE. He interviewed 37 children who had been given potentially mind-altering drugs, but none of these reported an NDE. But of the 12 children who survived a cardiac arrest or a coma, 8 (67 percent) reported an NDE. Morse’s research showed that psychological stress brought on by hospital admission for a serious illness or the use of powerful drugs was not enough to precipitate an NDE in children. The fact that children experience NDEs only in genuinely life-threatening circumstances is at odds with the findings of research among adults; adults’ fear of imminent death can sometimes trigger an NDE, a topic we will look at in more detail in a following chapter. Perhaps children do not experience fear of death because they are unfamiliar with the concept of death.

P. M. H. Atwater, a researcher who has had three NDEs herself, has carried out research into childhood NDE for many years.

2

She has spoken both to children who had an NDE and to adults who had one when they were young. Atwater writes that children can have an NDE at any age and that in the course of her research she came across extremely young children who, as soon as they could talk, told their parents about the experience or made a drawing. Children of up to three or four seldom have spontaneous memories of their experience. But there are exceptions: I have spoken to some adults who experienced an extensive NDE before the age of three and who were able to remember a great many details, even of their out-of-body experience. Children between the ages of three and six usually remember their NDE although children are really able to share their experience with others only from the age of twelve. With hindsight, people who had an NDE as a child, but no memory of it, realize that they have always been different from their peers:

I had a relatively normal childhood and thought that every now and then all people “sensed” things and had dreams like me. These things were never talked about. You get used to everything, and I was busy doing the things young women do: studying, getting married, having children, teaching. But then I suddenly came up against something….

People with an NDE at a very young age, but without any memory of it, sometimes have a second one later in life. During this second NDE they suddenly realize that they had one when they were little. They recognize aspects of their previous NDE even though the content of a second NDE is seldom identical to the first. The Dutch NDE study that my colleagues and I carried out produced striking evidence that cardiac arrest patients who had an NDE earlier in life were significantly more likely to have a second one than the other patients.

Circumstances That May Prompt an NDE in Childhood

The most common precipitants of NDEs in children are near-drowning and coma after head trauma, such as from a serious traffic accident. Other circumstances include coma caused by diabetes or by an inflammation of the brain, cardiac arrest caused by life-threatening arrhythmia, imminent asphyxia caused by an asthma attack, diphtheria, muscular dystrophy, or electrocution. It also seems that the anesthesia that was given in the past for tonsillectomy was a fairly frequent cause in children for experiencing an NDE.

The Content of a Childhood NDE

The content of a child’s NDE is similar in many respects to that of an adult although it usually contains fewer elements. Atwater found that for more than three-quarters of the many children she interviewed as part of her retrospective study, the experience begins on a positive note: a loving environment, a friendly voice, the encounter with a kind being or an angel, a sense of peace, and often an out-of-body experience coupled with perceptions of the body and the hospital surroundings, and traveling through a tunnel. About a fifth of the children witness a heavenly environment, while 3 percent report a frightening experience. Another possible element is the conscious return to the body, accompanied by feelings of disappointment because the experience had been so beautiful. During their NDE children are more likely to meet their deceased grandmother or grandfather than their parents. If an NDE were based purely on wishful thinking, one would expect children to meet living family members such as their father and mother. Children do encounter favorite pets that have died more frequently than do adults. At a very young age, children rarely experience a life review, but these are reported from the age of six onward. And finally, like adults, children find it extremely difficult to talk about their experience. Their attempts at sharing it with family and doctors often fall on deaf ears. Between thirty and fifty years may pass before they can discuss the experience and the sense of feeling different.

3

Changes After a Childhood NDE

The research of both Atwater and Morse into the changes that may follow a childhood NDE suggests that children too undergo a number of profound and typical changes that determine their outlook on life.

4

But a major difference is that adults, who had accumulated much life experience before their NDE, have to abandon old, accepted beliefs in order to integrate their new insights. Children, by contrast, have not yet been socialized into society’s prevailing mores, and so their understanding of life cannot be said to have changed. They accept their insight into life and death as normal and neither realize nor understand that other children and adults do not share these insights. Parents and teachers sometimes think that the child is difficult because he or she freely challenges their norms and values: “That’s not true, Mom!”

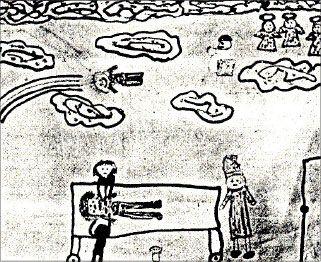

The out-of-body experience of a six-year-old girl during her near death experience.

The out-of-body experience of a six-year-old girl during her near death experience. From the collection of Dr. Melvin Morse.

At a young age these children are not yet aware of being different from their peers. They accept death as a part of life. They experience the death of their dog or cat differently than do their siblings and friends, and they do not realize that their daily reality of an enhanced consciousness, with empathy for others through a heightened intuitive sensitivity, is not shared by other children. Children with an NDE listen beyond the spoken word; they understand why things are said in a certain way.

After a near-death experience children feel a fundamental sense of loss that they cannot put into words. The beauty and peace that they encountered during their experience are gone. They have a tendency to withdraw from their peers, and they often watch from the sidelines rather than mix with other children. They cannot bear piercing sounds or noise and tend to like peaceful, classical music from a young age. They have an unspoken need for a sense of security, comfort, understanding, warmth, and genuine interest and attention. At a young age they are sometimes found to communicate with invisible beings they call angels or friends. And although they suspect that their understanding surpasses that of their peers, they are incapable of talking about this. They do not want intellectual talk but prefer to be addressed at an emotional level. During religious instruction in school they can drive everybody to distraction with their never-ending questions. Mentally they are far too mature for their age, and they may run the risk of avoiding the playful behavior typical of most other children their age.

5

By high school, about a third of these children develop alcohol- or drug-related problems, to which they may be much more sensitive than their peers. A short attention span, caused by a flood of (involuntary) impressions and resulting in disruptive or hyperactive behavior, sometimes earns them an ADHD diagnosis. At this age they can also become depressed or develop suicidal tendencies. This period is often characterized by repression rather than acceptance and integration.

6

Children who have had an NDE are alert, astute, and often highly intelligent. They often go on to study philosophy, theology, or physics. Alternatively, they may opt for one of the creative professions, such as painting, photography, or music, to express the emotions they struggle to put into words. Keen to help others, some opt for a career in health care and become nurses, doctors, or social workers. They want to work in a field that allows them to draw on their heightened intuition.

It is up to parents, guardians, teachers, psychologists, and other health care practitioners to try and approach these children without prejudice. Information about NDE and its effects is absolutely crucial to better understand these children and help them grow up—to facilitate a process of integration instead of the often-subconscious process of repression.

7

Spontaneous Out-of-Body Experiences (OBEs)

A report of an out-of-body experience at an early age does not necessarily mean that somebody had an NDE as a child. In young children especially, spontaneous out-of-body experiences also occur in situations that are not life-threatening. About 10 percent of the general population and perhaps up to 25 percent of children and adolescents have had a spontaneous sensation of being outside the body, usually on the threshold between waking and sleeping. These data have been extrapolated from a scientific survey among 475 Dutch psychology students in 1993. Of these students, 22 percent reported a spontaneous out-of-body experience while 7 percent reported two to five such experiences. A comparable study from the United States found spontaneous out-of-body experiences among 25 percent of students and among 14 percent of the rest of the population in the same city.

8

There are reports of adults who, after a childhood NDE, had frequent spontaneous out-of-body experiences, both during the day and while sleeping. Their NDE not only created a sense of enhanced consciousness with heightened intuition, but also increased the incidence of spontaneous out-of-body episodes.

Sexual abuse and the threat of physical or mental abuse, which may trigger an out-of-body episode as a protection from pain and humiliation (so-called dissociation), are much more common among children than previously assumed. These episodes do not qualify as spontaneous out-of-body experiences. Child abuse often goes undetected, and social workers tend not to ask targeted questions about either abuse or dissociation with out-of-body experiences. Raising the subject with parents and children remains taboo. And children seldom volunteer to talk about their experiences. Because children not only cease to have physical pain during such an experience but can sometimes also see their body and what happens to it from a position outside and above their body, an out-of-body experience is more than just dissociation. Specialist literature defines dissociation as the escape from the frightening reality of a trauma or “the disruption of the normal integrated functions of identity, memory, or consciousness.” It does not make explicit mention of the possibility of verifiable perception from above and outside the body. Kenneth Ring’s research provides reasonable evidence of a link between out-of-body experiences caused by childhood trauma and the later occurrence of an NDE.

9