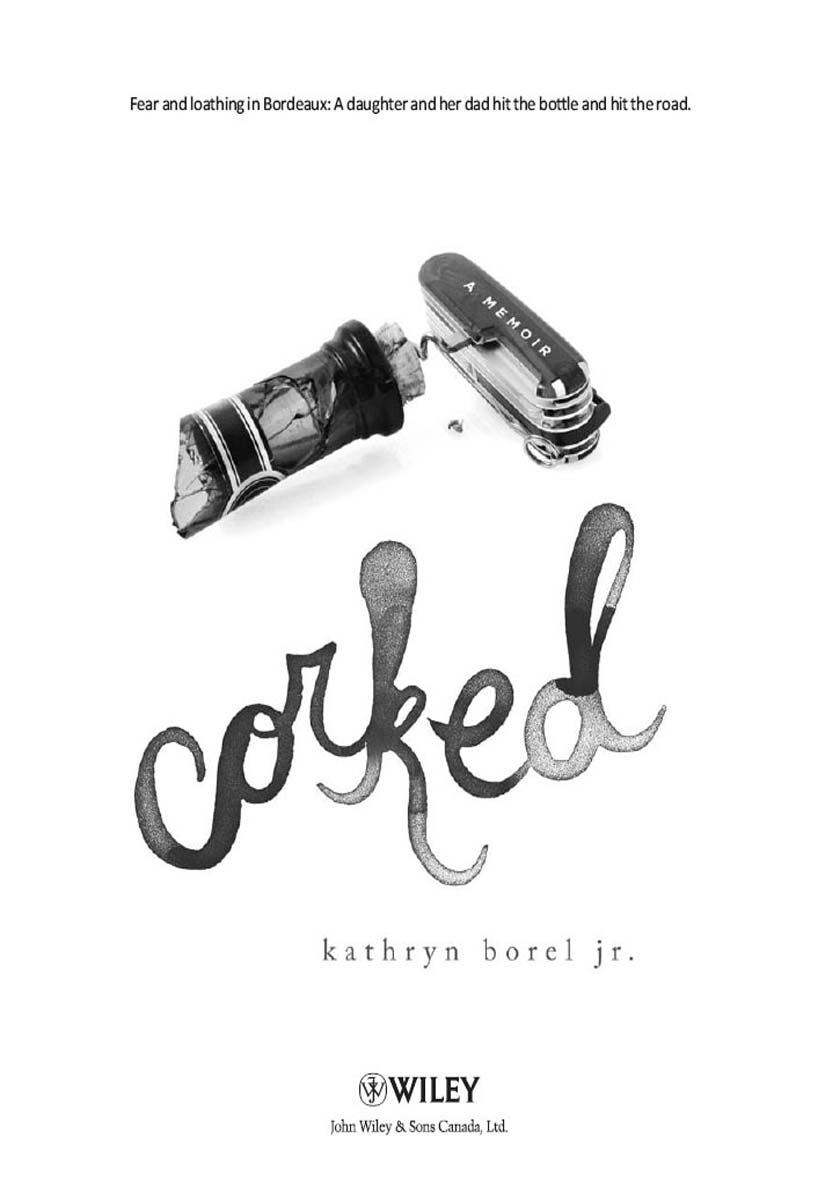

Corked

Authors: Jr. Kathryn Borel

Â

Contents

Â

Copyright © 2009 by Kathryn Borel

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or used in any form or by any meansâgraphic, electronic or mechanical without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any request for photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any part of this book shall be directed in writing to The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free 1â800-893â5777.

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free 1â800-893â5777.

Care has been taken to trace ownership of copyright material contained in this book. The publisher will gladly receive any information that will enable them to rectify any reference or credit line in subsequent editions.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Borel, Kathryn

Corked: a memoir / Kathryn Borel.

Corked: a memoir / Kathryn Borel.

ISBN: 978-0-470-67585-4

1. Borel, Kathryn. 2. Borel, Phillipe. 3. Wine and wine makingâFrance. 4. FranceâDescription and travel. 5. Fathers and daughtersâBiography. I. Title.

1. Borel, Kathryn. 2. Borel, Phillipe. 3. Wine and wine makingâFrance. 4. FranceâDescription and travel. 5. Fathers and daughtersâBiography. I. Title.

DC29.3.B67 2009Â Â Â Â Â 914.40484Â Â Â Â Â C2009â901884-5

John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd.

6045 Freemont Blvd.

Mississauga, Ontario

L5R 4J3

6045 Freemont Blvd.

Mississauga, Ontario

L5R 4J3

Â

For my family

Â

W

hen it comes to champagne and our family, my father has only one absolute rule: We do not drink it when we are sad.

hen it comes to champagne and our family, my father has only one absolute rule: We do not drink it when we are sad.

In the pebbled courtyard of this audaciously French bed and breakfast, my father and I stretch our limbs. His arms flap out, parallel to the expanse of pigeon-gray pebbles, his palms wide and splayed, as though he's holding the most gigantic pair of hedge clippers and is just about to cut a bush into a topiary of a cock. The rooster kind. He flings his arms as wide as they'll go, pulsing them over and over. As he flings, he spits out a sequence of vowels found in Dutch words, “OO! EE! AA! OO! EE! AAAAA!”

I drop my head to my knees and hang there, feeling the xylophone-click of my vertebrae, smelling the wind that bursts around us. It's fresh and animated, loaded with invisible particles that blow off the clusters of fruit from the vineyards surrounding the B&B. The vineyards go on and on, interminable grids of interminable rows of interminable vines. The stone house looks besieged by the vines, as if it could, at any moment, be overtaken by these squat spiky plants, should they decide to uproot themselves, devise a plan, walk the short distance, and begin a good old rampage of vine-thrashing destruction.

Pressing out the last bit of air from the bottom of my lungs, I pop up and jog over to my father, punching the air with each step. When I arrive at his puffed chest, I reach out my hand, which I've formed into a claw, and pantomime tearing out his heart. I hold the heart in one hand, turn around, and drop-kick it into the nearest field, which is now turning all iris and gold as the big country sky shuts down for the day.

“Thank you, Tou Tou. I didn't need that old thing anyway,” he says. Tou Tou is my French nickname. It is slang for “baby dog.”

“Suze-la-Rousse.” I say the name of the town we're in like a proclamation.

“

Suce la rousse

,” my father mispronounces on purpose.

Suce la rousse

,” my father mispronounces on purpose.

“Suck the redhead,” I translate.

“Yesssss! I've done this many times.” Maybe he is making a joke.

“Gross. Suck the redhead. Gross.” But I laugh, because we've just come from a terrific wine tasting in the glorious Rhône Valley, in the vineyards of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The owner's wines tasted of delicious cake, and in his relaxed southern French manner, he'd opened more than a dozen bottles for us to sample. I couldn't bear to spit any of them out, so I swallowed and swallowed each sip of delicious cakey wine. Now, with all this new gulped air and the remains of the booze, I have become a little drunk again. My father shouldn't have allowed me to drive. I shouldn't have allowed me to drive.

When we rap on the glass door of the stone house, a small pitbullish woman greets us. She is in her early thirties, and has a wide-eyed, moonfaced baby perched on her hip. She allows us to take two steps into the front room, then blocks our passage. Immediately, she sniffs out my accent.

“Americans?” she asks in English. Her accent is convincing. This is a shock to vaguely-drunken me, considering her house is in a tiny village and she's surrounded by more plants than people.

“Canadian, actually,” I respond in English, “but my father here is French. French from France. This Franceâhere.” I point twice at the ground to show her what France I am talking about. “Paris.” I point up, where Paris lives.

“Oh.” She seems disappointed. “I used to work in America. I was a catering manager for a hotel in Washington, D.C.” She says this fast; she seems ravenous for conversation.

“That's what my father does. He's a hotelier.” My father momentarily takes his attention away from wagging his index finger in front of the baby's face and nods to corroborate my statement. He immediately goes back to the baby, letting his finger slice through the air slowly, left and right, left and right. He looks like a cop administering a sobriety test to a tiny impaired driver.

“I admire the American work ethic. I want to go back there. Do you know the French unions are petitioning for even

shorter

weeks? Thirty-one-and-a-half hours. It's lazy. I can't stand it. But my husband is based here. That's why we opened the B&B. I want to leave this shit hole,” she sputters.

shorter

weeks? Thirty-one-and-a-half hours. It's lazy. I can't stand it. But my husband is based here. That's why we opened the B&B. I want to leave this shit hole,” she sputters.

I do a slow 180-degree turn to gaze out her door. Magic hour is in full, foolhardy effect, frosting the gnarly vines with platinum. Bars of golden light poke through the surrounding tree branches, most still covered with leaves the color of cartoon fire. Startled by something we do not see, a beige cluster of birds explodes skyward. I turn back and examine the interior of her home: the thick, gray-brown high beams, the exposed stone walls, the smooth octagon terra cotta tiles, the wide bay windows bracketed by fresh linen curtains, sheer and bright.

“I see what you mean,” I respond. I reach out my hand for the keys and tap my fingers gently to my palm. She rests them there and tells us where our rooms are.

We thank her, exit, and walk along the grass path that leads to a row of individual coach houses. We dump our bags in our neighboring rooms and cross-inspect each other's living arrangements. We both have stone terraces and delicate wrought-iron tables outside. Inside, four-poster beds and mosquito nets and large bathrooms with clean porcelain and clawed tubs.

“Dad, she's right, this place is a real shit hole.”

“Toots, let's go out and celebrate

zees

shit-hole town and our shit-hole trip,” he says. “We'll have some nice dinner, some nice champagne.”

zees

shit-hole town and our shit-hole trip,” he says. “We'll have some nice dinner, some nice champagne.”

After I splash a quart of freezing water on my face and resurrect, 50 times, the lost art of the jumping jackâfor sobriety's sakeâwe climb back into our rented Citroën Picasso and trek south to a restaurant in Châteauneuf. My dad has a nebulous memory of an unforgettable meal he'd had there once, several years ago, on another wine trip with my mother, Kathryn Borel Sr. Her nickname is Blondie because of her hair. That was also the name of Hitler's dog, though my father claims these things are unrelated.

“

Eet

was truly memorable,” he says as we pass the white sign that confirms we are in the correct town.

Eet

was truly memorable,” he says as we pass the white sign that confirms we are in the correct town.

“Which way?”

“I can't remember.”

“Should I go in the direction of the

centre-ville?

”

centre-ville?

”

“Why not.” He is distracted by something again. Earlier in the day, he'd had a bizarre moment in the car before we were about to meet the vineyard owner at Châteauneuf-du-Pape. He'd sat there, sullen and impenetrable, inhaling through his front teeth like he were about to say something. When I reached out to touch him near the little rogue hairs next to his left eyebrow, he swatted my hand away without kindness. I had placed both hands on my knees and stared at them until the owner of the wine house, René Aubert, burst into the courtyard, an arachnid man, all spindly legs and arms.

“Is this ringing any bells?”

“Not yet,” he says.

I wait a beat.

“What about now?” I make a joke, hoping it will lift this new strange mood that's in the car.

“No sirree,” he says in a quiet voice.

We pass some trees. The sun has set and their branches are ugly in the dark.

“Now?”

“Okay Toots. Enough.” He reaches over and pats my knee. I glance over at him. He blinks heavily.

I focus on being a good driver for himâsmooth and calm, no jerky turns or hard brake-pumps. Maybe he is just hungry and tired. Also, his bum knee was acting up today. Sixty-six-year-olds with bum knees become cranky when they are not fed on time. The goal is champagne; our night will be happy.

“Oh!” he exclaims.

“Something familiar?”

“No. I forgot my

bréviaire

.” For the last 30 years, his dining ritual has been to make tasting notes on all the wines he selects and drinks. He scrawls them in his illegible chicken scratch in his leather-bound day planner. But napkins and coasters are always an option for those scribbles. He is being difficult.

bréviaire

.” For the last 30 years, his dining ritual has been to make tasting notes on all the wines he selects and drinks. He scrawls them in his illegible chicken scratch in his leather-bound day planner. But napkins and coasters are always an option for those scribbles. He is being difficult.

“Dad. Listen. I brought my desk calendar if you need to make notes. Help me out here. Can you at least tell me where to park?” There are street spots available, but our car won't fit into them.

He ignores me and goes back to focusing on something else, so I settle on a parking lot at the bottom of a hill that leads up to where I surmise the restaurant will be. Getting out of the car and looking at the slope up ahead, I immediately know he's going to complain about the walk. I wonder if I'm trying to provoke a reaction.

“But Tootsie, the hillâmy knee. My poor knee!” I ball up my hands into fists, squeeze, and release. He whines like a child.

“We can take the hill slowly, Dad. Okay? There was nowhere to park up there. I. Will. Help. You.”

“Thank you. Thank you, Tootsie.” Three glasses of champagne pop into my head, bowing to me, then to one another, before lining up in front of my grabby hands. I imagine draining the trio in rapid sequence and hiccupping merrily. Problem? There is no problem. Problems are for those who lack champagne.

It takes 15 minutes for my gimp to shuffle his way up the hill and into the town square. Each of the four sides is quaint. In the middle is a fountain. Surrounding it are two bistros, one bar, and one restaurant. Faint music and lights pour out of each.

“So. Daddy. Which one is it?” I ask. I am careful about making my tone even. Maybe he is mad or sad or tired or hungry or some emotion I've never heard of.

“Hmm.” He turns around and aroundâa dog chasing his tail in extreme slow motion.

“Dad, I don't want to rush you. I am eager to eat a memorable meal at this memorable restaurant. But I am also very⦔ I stop myself before I say the word “hungry” because I am worried that my needs will make him annoyed.

“Yes, yes, Toots. I think it isâ¦ehâ¦this one.”

“La Garderie.”

“Yes. But I can't remember for sure,” he says dismissively, withdrawn. He feels like a bomb or a snail.

“Great then. Good enough.”

We enter. There is a bar. We stand in front of the bar, waiting to be seated in the dining room next door. Waiters come and go, making drinks behind the bar and carrying them to tables, not acknowledging us. My dad lets out a sigh. If only this sigh were louder, and were accompanied by a translator, or a Geiger counter. Our family would have avoided countless hospitality disasters if a person or little machine screamed toxicity reports at the staff. These nights always, always, ALWAYS begin with a sigh, and, if the crappy status quo is maintained, always, always, ALWAYS end with my dad's invective equivalent of Mount Vesuvius. Too many times I've watched him grow chilly and dismissive with a waiter for accidentally bringing wine from the wrong year, or blast the food and beverage manager of a hotel for allowing any soft triple-cream cheese, like Brie or Camembert, onto a complimentary cheese platter set in my dad's room as a VIP gift. (Soft triple-cream cheeses stink up the room. Hard cheeses are acceptable.) There's a minefield element to traveling with my father. “I love making people feel like

sheet

about themselves,” he says, “I would like to teach a university course in this.” My father's boundaries are elliptical and though they're impossible to predict, stepping over them is an exercise in arbitrary terror. It would take a team of good Jungian men to properly navigate them. Stepping outside the line is usually fine. And other times you get your face and limbs blasted off.

sheet

about themselves,” he says, “I would like to teach a university course in this.” My father's boundaries are elliptical and though they're impossible to predict, stepping over them is an exercise in arbitrary terror. It would take a team of good Jungian men to properly navigate them. Stepping outside the line is usually fine. And other times you get your face and limbs blasted off.

I turn toward my father and tug on the sleeve of his navy blazer. He has cleaned himself up for our champagne dinner. His peppery-gray hair is elegantly combed back, his smooth tan face is as brown as nuts and softly moisturized. His once-full mouth now droops a bit from age, but it remains firm above a strong jaw and tall neck. He is a fine gentleman, a movie star from the 1950s or 1973.

“Dad. Please. Please please please. We'll be seated, I'm sure of it. They have to seat us! It's the way these things work. It took us a while to get here, so three more minutes will not be the end of the world,” I say, knowing full well that three more minutes could, in fact, be the end of the world.

“Tootsie, you're right. This is a night of celebration,” he says.

I sigh a sigh of relief.

A young waitress wearing a great deal of gold eyeliner sways over to us.

“Vous voulez manger?”

Would we like to eat? Yes, we would. My father takes in a quick breath and straightens himself so that he's at his maximum towering height. Before he can say, “Well, what the fuck else would we be here for,

connasse?

” I grin and respond,

“Avec plaisir.”

Would we like to eat? Yes, we would. My father takes in a quick breath and straightens himself so that he's at his maximum towering height. Before he can say, “Well, what the fuck else would we be here for,

connasse?

” I grin and respond,

“Avec plaisir.”

She leads us to a prettily dressed white table with a little candle. Upon returning to the back section of the restaurant, she begins to joke with another waiter, a hot, chiseled man with a hairdo like the wig of a Lego figurine. My father watches her, unblinking. The temperature in my earlobes shoots up as I crane my neck around to see if she's making appropriate serving progress. I feel a fleeting warmth in my chest and bathing suit area for the hot waiter, but I'm too worried to indulge in the abandon of server lust fantasies. Maybe I think about him sucking on my wine-stained lower lip for one-half of one second, but I'm really just praying silently and laser-focused on the pile of untouched wine lists.

Other books

Extraordinary Zoology by Tayler, Howard

A Wedding Quilt for Ella by Jerry S. Eicher

The Monstrumologist by Rick Yancey

The Removers: A Memoir by Andrew Meredith

Tempted Again by Cathie Linz

A Nashville Collection by Rachel Hauck

On the Run by John D. MacDonald

Pagan's Vows by Catherine Jinks

The Vanishing Stone by Keisha Biddle