Cornbread Nation 2: The United States of Barbecue (Cornbread Nation: Best of Southern Food Writing) (43 page)

Authors: Unknown

Instead, I smile and nod and swallow hard. This is not one of my prouder

moments: rather than give Blanche and Herbert a chance to explain themselves, rather than lay claim to the bully pulpit for myself, I defile the hospitality of my hosts and deny the empirical truth of my research.

Later that afternoon, I return home from the library to find that Blanche

has left a message on my answering machine. "I found an old matchbook

from the restaurant," she says. "Stop by the house tomorrow and I'll give it to

you as a souvenir. Ain't too many of these left, you know."

Tennessee's Oldest Business

Ron Dawson demonstrates his favorite magic trick as he stands behind the

cash register at St. John Milling Company. Dimes and quarters disappear and

reappear in quick succession. Then, unlike television or tableside magicians,

he explains the mechanics of the trick. Gives the whole thing away gladly. No

secrets. Despite his dexterity with the coins, he knows that deception has no

place in the milling business. It's a line of work based on honesty, a trait

handed down for nearly 225 years through the families that have run the oldest business in Tennessee. A sign on the building reads, "Please weigh with

driver off truck."

On the banks of north-flowing Brush Creek in Northeast Tennessee, St.

John Milling survived Yankee raids in 1862 and the coming of the discount

stores a century later. It escaped the domination of cheaper Kansas wheat by

milling animal feeds instead. Still, the owners have yet to buy a computer. Ron

Dawson says, "It's coming," but adds quickly that if such a machine is purchased, he wouldn't want it to show.

Yet Ron and his eighty-nine-year-old father-in-law, George St. John, don't

fight technology. Ron is trained to be an audiovisual communication specialist. George took a decaying, out-of-date mill, applied his newly acquired engineering knowledge from the University of Tennessee, and began modernizing

the business during the pain of the Great Depression in the 193os. The census

of 19oo reported over forty mills in operation in Washington County. By midcentury, most all of them were boarded up. Seeing a dim future in grinding

corn and wheat, Dawson and St. John bought equipment from some of those

closed mills and created a farm store and feed mill. Ten years ago, the bulk of

their business was cattle feed, but today, it's sweet feed for horses, a combination of cut corn, crimped oats, wheat bran, protein, soybean meal, minerals,

and vitamins which is then run through a molasses blender. It nourishes 200 pound ponies, 2,000-pound draft horses, and all sizes between. Vestiges of the

mill's original purpose sit on the shelves today as biscuit mixes purchased

from North Carolina.

The earthy smell and creaky floors of the Southern feed store, the rush of

the cool creek just outside the back door, and a hot pork-tenderloin biscuit

from the neighbors at T and S Country Kitchen make the St. John Mill one of

East Tennessee's most beloved places. Farmers know they can come by and

find a new T-post for fence-mending or a pulley for the barn. There's Grape

Balm Hoof Healer, too. Gopher bait and apple-flavored horse treats. Along

with each purchase comes the timeless wisdom of the feed store proprietor.

Buy the Have-a-Heart trap and you learn the best way to catch raccoons. The

folks at St. John were battling an unusually large population of the animals

one year when a customer suggested baiting the traps with marshmallows.

"The next morning, we had two 'coons in one trap," Dawson says. More

good advice: take a trip with the catch and transport the animals a minimum

of seven miles from where they were caught. Make it only six, Dawson says,

and they'll revisit.

It's the age-old exchange of information and stories, opinions and predictions that has taken place on courthouse benches and in country stores in

these Appalachian Mountains ever since settlers got together in 1772 to organize the Watauga Association, America's first independent government. It

wasn't long after that when Jeremiah Dungan, chased off a British hunting

preserve in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, found a small, falling stream with a

sixteen-foot gradient that could be harnessed for milling, unlike the nearby

Watauga River. By 1778, he was in business on Brush Creek. Farmers shelled

their corn by hand and brought their "turn" in special cotton sacks. "The

miller dipped his toll box into the grain to get his share, usually about seven

or eight pounds per bushel," says George St. John. When fall harvest time

came, settlers and their families camped outside the mill and talked politics

with their neighbors until it was time to grind their wheat or corn.

St. John Mill may well be the oldest manufacturing company in the United

States. Tennessee governor Don Sundquist chose it for the opening of the

state's bicentennial celebration in 1996. "No one was wanting money, no one

wanting favors," George remembers. He enjoyed the party so much that he's

planning another one for the spring of 2003, when he turns 9o and the mill

225. His grandfather bought the mill in 1866.

"I've been very lucky," he notes. "I've been my own boss for sixty-six years.

I make my own decisions, handle my own problems. Something would break

and I'd be here nearly all night fixing it. Or maybe a cow would be out on our adjoining farm and the police would be after me. Two o'clock in the morning

and I'm out hunting a cow."

With a book of deeds, letters, and tax records dating back to 1784, George

has become an amateur historian. He and Ron Dawson, who purchased the

business from his father-in-law in 1975, have thought long and hard about

how the mill made it through the Civil War, especially the bullets and the

flames of Carter's Raid the day before New Year's Eve, 1862.

Brigadier General Samuel P. Carter had taken a leave of absence from the

U.S. navy to fight the Confederates on land. In 1861, his warmongering retired

Presbyterian minister brother William had met with President Lincoln and

his staff to describe a plan for the destruction of all the bridges on the East

Tennessee and Virginia Railroad between Bristol, Virginia, and Bridgeport,

Alabama. Lincoln readily gave Carter an audience because the plan meshed

well with the Federal strategy of using East Tennesseans' Union loyalty to its

best, most deadly advantage against their Confederate neighbors. The bridge

spanning the Watauga River, at Carter's Station, was on the hit list. According

to Jim Maddox, in the History of Washington County, Tennessee, published in

2001, "a Federal cavalry force of Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania troopers,

some armed with Colt revolving carbines and led by General Samuel P. Carter,

came down from Kentucky to attack the railroad bridges.... Destroying the

bridge there (at Zollicoffer), the Federal cavalry went on to attack the Confederate garrison at Carter's Depot, and after a brisk fight there, captured most of

them, paroling the prisoners, and destroying the bridge there as well as some

ten railroad cars filled with lumber and other military supplies." One account

says Carter drove a locomotive into the river.

Robert Tipton Nave, in the same publication, describes yet another assault

in September of 1864, when Union men attacked the enemy at Carter's Depot,

forced a retreat, but left before a larger Confederate contingent could come to

defend the bridge. The Barnes house on Brush Creek, near the mill, was rattling with crossfire, and Mrs. Barnes packed her baby and three small children

into the chimney while she crouched inside the fireplace for protection.

Ron Dawson and George St. John believe the only reason the mill escaped

the raiders' torches is because it was run, during the Civil War, by Henry

Bashor, a Dunkard minister who led Sunday services in the building. Bashor

had purchased the mill in 1846, and his accounts were scattered throughout

the South-Savannah, Atlanta, Birmingham, Huntsville-after the completion of the railroad from Bristol to Knoxville in 1856 opened up a whole new

market.

"It's hard to conceive how this mill survived, being 500 yards from where Carter's Raid happened, and being an established mill grinding wheat and

corn when soldiers from both sides were frantically trying to cut supply lines

for food and ammunition," Dawson says. "The only theory we find plausible

is that it was used as a house of the Lord and therefore spared."

A highway bridge wasn't built over the river until 1913. To reach the mill

from the other side of the Watauga, customers had to use a ferry or risk a dangerous crossing on foot at a swift and rocky ford. Still, the mill survived.

East Tennessee, immediately after the Civil War, was considered the "bread

basket of the South," says George St. John. "While much of the South was torn

up during the war, there was very little damage here, and the mill's customer

base expanded." The Read House in downtown Chattanooga, once an army

hospital during the Civil War, baked with cornmeal and flour from the St.

John Mill.

Today, even St. John's competitors are customers, and they often pool their

money to buy truckloads of goods, such as fenceposts, to get a better price

break. Back in the middle of July, two of Dawson's four employees had to miss

work because of illness. Instead of turning to the want ads or temporary employment services, he was aided by a competitor. Mike Galloway, at Galloway's Mill in Sullivan County, sent one of his employees over to St. John for

two days and would accept no pay.

"Back thirty years ago, Galloway's had a building burn," Dawson explained.

"George St. John sent over a truck and men to help them get back on their

feet, and they never forgot it. You don't see that in business today."

The majority of the nation's oldest businesses, like St. John Milling, exist in

rural areas, and Dawson believes they are organizations that have gotten past

the idea that the only reason for their existence is to make money.

"We're working to give service, to help others. We've arrived when you have

a businessman come in and you see him reach up and get his tie and loosen it.

That action says I don't have to put up a front for anyone. I can be myself. I

think it's the way the Good Lord wanted us to be."

I take yet another drive out Highway 400 to refine my loafing skills at the

best place I know to do it. Shirley Casey slips me a country-ham-and-egg biscuit through the window of T and S Country Kitchen. There are fifteen different kinds of biscuits, ready around 6:35 in the morning. I find a seat at one of

the old stone picnic tables on the banks of Brush Creek, right between the mill

and the restaurant. I listen to the creekwater and hear cattle around the corn

crib in the pasture just across the road. I step inside the mill for a good story

and the smell of oats. And an even slicker magic trick. I overhear a customer

telling about how the real estate agents are bringing too many Floridians through Roan Mountain. I pick up one of David Cretsinger's cypress wood

buckets, at a third of the Dollywood price, and contemplate buying one of his

butter churns on the next visit. Today I learn what the percentage figure

means on the horse feed. I find out what made a good buhrstone. I hear

George St. John speculate about where the original Fort Watauga could have

been. Maybe right across the road. I hear Ron Dawson count his blessings for

never taking that job in Chicago or the one way out in Stockton, California.

And I come to appreciate, even more, the richness of life in East Tennessee,

thanks to the wisdom within these old walls.

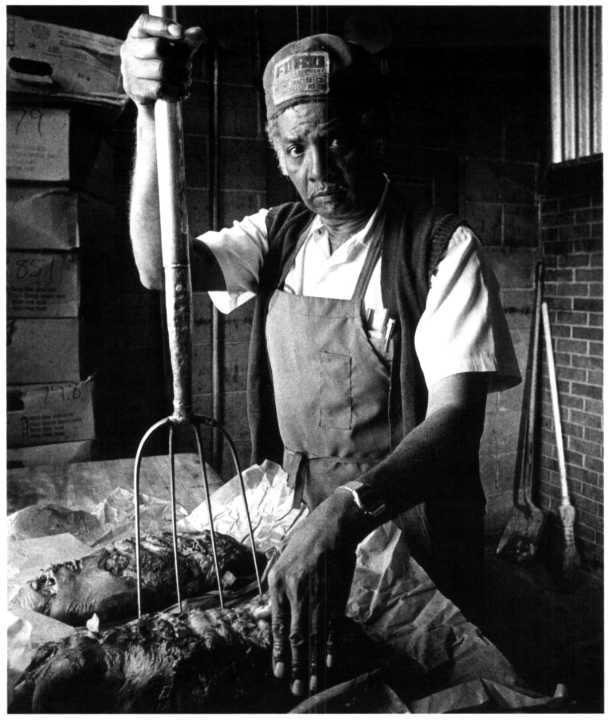

Pitmaster James Willis, Memphis, Tennessee

Al Clayton of Jasper, Georgia, shot the photographs in this section.

Some were originally published in John Egerton's Southern Food: At Home,

on the Road, in History; some were published in magazine articles and in

other books. Over the course of a long and distinguished career, Clayton

has had a profound influence on how we see the South. During the i96os,

he took photographs for a U.S. Senate investigation on hunger. Those

images were a catalyst for passage of the food stamp program.

(Photographs used by permission of the photographer)