Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors (44 page)

Read Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors Online

Authors: Stephen Ambrose

Tags: #Nightmare

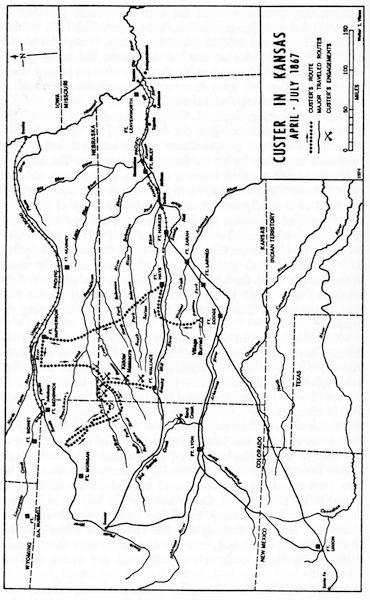

When Custer arrived on the Smoky Hill he discovered that the fleeing Cheyennes had gone on a rampage. Road travel of the whites had come to a halt. The stagecoach stations, located about ten miles apart along the Smoky Hill River route, had been burned. At Lookout Station, fifteen miles west of Fort Hays (the Army’s major post in central Kansas), Custer discovered the buildings in ashes and the bodies of three dead station keepers. Hancock had stirred up an Indian war and here was Custer, in the middle of Indian country at the head of a regiment of cavalry, and he had not seen a single Indian since leaving Pawnee Fork. His horses were exhausted, his men were grumbling, Hancock could not believe Custer had not caught at least one Indian, Custer had shot his best horse, his own men had attacked his camp, travel had come to a halt along the Smoky Hill line (and keeping that line open was a major objective of the Hancock campaign), and the Cheyennes were on the loose north of the Smoky Hill, in a mood to kill any whites they encountered.

Matters could not have been much worse, it seemed, but they soon became so. Hancock, furious at the Indians for running away, burned their village at Pawnee Fork. Correspondent Stanley reported that

251 tipis were burned, along with 942 buffalo robes and all kinds of household equipment. Stanley estimated that it would take three thousand buffalo to replace the skins used in the tipis alone. The cash value of the loss was around $100,000 or close to a million dollars in today’s terms.

46

According to George Grinnell, who later interviewed many of the Cheyennes involved, Hancock set the torch to the village

before

the Indians struck the Smoky Hill line, and they went on the warpath in retaliation.

47

Whatever the truth of the matter, the burning of the village hardened the Cheyennes’ determination to make war.

Custer, meanwhile, limped into Fort Hays with his troopers on May 2, 1867, hoping to find fresh horses and plentiful supplies. He discovered, instead, a woebegone collection of log shanties and sod huts, with neither horses nor supplies. Custer was immobilized. With no forage available, he would have to stay where he was until the horses fattened up on the spring grass.

Hancock, meanwhile, had marched the infantry back to Fort Larned, where he delivered a war-or-peace ultimatum to Arapaho and Kiowa chiefs from camps south of the Arkansas. The Kiowa war leader Satanta impressed Hancock as being so desirous of peace that the American gave him a major general’s dress uniform. Then Hancock left his infantry and traveled north to Fort Hays, where he took one look at the wretched situation, muttered that he would hasten the shipment of supplies when he got back to Fort Leaven-worth in eastern Kansas, and shook the dust of the Plains from his heels. And that was the end of the grand Hancock expedition of 1867.

While Custer sat at Fort Hays waiting for the grass to come up, the Indians in Kansas had a fine time. Arapahoes, Kiowas, southern Oglalas, and southern Cheyennes struck repeatedly at mail stations, stagecoaches, wagon trains, and railroad workers on the Platte, the Smoky Hill, and the Arkansas. Railroad construction came to a halt.

48

The Kansas frontier was in a panic. Dozens of whites were killed and women and children captured. Fort Wallace, in western-most Kansas, was under a state of siege. At Fort Dodge, to the southeast, Satanta put on his major general’s dress uniform and then ran off the horse and mule herd. “He had the greatest politeness,” Davis reported, “to raise his plumed hat to the garrison of the fort, though he discourteously shook his coattails at them as he rode away with the captured stock.”

49

All the while Custer sat at Fort Hays. His major problem—aside from the embarrassment of knowing that the Indians were running

wild while he was immobilized—was the same one Red Cloud and Crazy Horse had faced the preceding winter: Custer’s men were deserting in droves. Between October 1, 1866, and October 1, 1867, in fact, the 7th Cavalry lost 512 men by desertion, more than the equivalent of its total field strength.

50

The deserters were replaced, although slowly, but enlistees in 1867 were of a low order and none of the men received any training before being sent to the field. Most could not even sit a horse.

The major reasons for the desertions were beyond Custer’s control. Many enlisted men had joined the Army in the east in order to obtain free transportation west. Once in Kansas, the lure of the gold fields in Colorado and Montana was too much for them, and they took off. Secretary of War Stanton once remarked that the best way to populate the West was to keep sending recruits out there. The more general cause of desertion, however, was the Army’s wretched treatment of enlisted men, which contrasted so sharply with the relatively decent food and housing available to Custer and the other officers. The men were issued bread that was five years old or older. At Fort Hays and throughout the frontier they slept two to a bunk, on rough wood mounted in two or even three tiers. Kitchen slops were emptied into crude sewers close to the barracks, which soon became clogged with grease, producing foul odors and attracting flies in swarms. Aside from stale bread, the principal staples were beef, salt pork, coffee, and beans, all in insufficient quantity. So inadequate was this diet that many of Custer’s men suffered from scurvy.

51

Custer divided his men into teams for competitive events, such as foot and horse races or buffalo hunts, in an effort to maintain some modicum of morale, but it did little good. Each night a few more men left for the gold fields. They took their chances with the Indians, who were practically besieging the fort.

For his own morale, Custer decided to send for Libbie, regardless of the threat of the Indians. The day he arrived at Hays, Custer wrote her, telling her “Come as soon as you can. … I did not marry you for you to live in one house, me in another. One bed shall accommodate us both.”

52

The next day he told her to bring a good supply of butter for the officers’ mess, along with lard, potatoes, and onions. “You will need calico dresses, and a few white ones. Oh, we will be so,

so

happy.” Wagon space was scarce and his men needed every bit of supplies they could get, so Custer told Libbie not to be too outrageous in her requests for space. He advised her to leave her huge clothes-press at Fort Riley. By May 6 his anxiety

to be with her was nearly too much for him to bear. “I almost feel tempted to desert and fly to you,” he wrote Libbie. “I would come if the [railroad] cars were running this far. We will probably go on another scout shortly, and I do not want to lose a day with you. Bring a set of field-croquet.”

53

Libbie came, bringing a young unmarried friend with her, and of course Eliza and the cook stove. Libbie was disappointed with the primitive fort, but she was with Autie and that was enough to make her happiness complete.

54

With Libbie around, Custer’s spirits began to revive. The weather helped, too; there are few places in the world more delightful than Kansas in May. The grass was coming up and his horses were putting on weight; supplies were beginning to arrive from Fort Leavenworth; he had a campaign to look forward to. This time there would be no doubt about the Indians’—or the Army’s—intentions. Hancock had started a sure-enough Indian war, and Custer could take the field with the knowledge that any Indian he encountered was fair game. The Army up north might not be able to control the northern Oglalas—Crazy Horse and his associates at this time were again blocking the Bozeman Trail—but down in Kansas, Custer intended to teach the rampaging red men a lesson they would not forget. In the process he hoped to add a little luster to his suddenly tarnished reputation.

13. Custer, the Crow scout Bloody Knife (on Custer’s right), other Indian scouts, and two of Custer’s dogs pose in front of a Northern Pacific Railroad tent during the Yellowstone River expedition of 1873. The dogs loved to chase antelope, and Custer often left the column, even in the middle of hostile territory, to join the hunt.

14. Spotted Tail, the great Brulé leader who had an enormous ego and the talents to back it up. He was Crazy Horse’s uncle and reportedly the most fearless of all Sioux warriors. The first to take up arms against the whites (in 1854), he was also the first important Sioux leader to become an advocate of peace (1864). He made frequent trips Washington to consult with the Great White Father; photograph was taken in Washington in 1875.

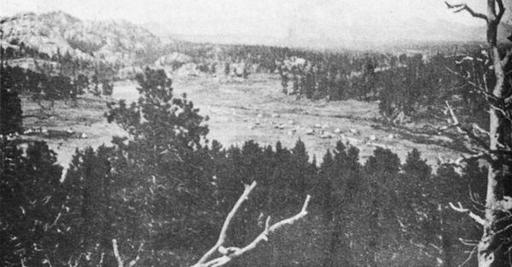

15. Custer’s camp at French Creek in the Black Hills, 1874. At this spot, two miles east of present-day Custer, South Dakota, the expedition found gold. In his official report, which he gave to the newspapers, Custer gushed about the Black Hills. Not only was there gold literally at the grass roots, but magnificent scenery, perfect weather, and the best farming and grazing country in the United States—or so he said, thereby helping start the Black Hills gold rush.

16. Custer and Libbie in Custer’s study at Fort Abraham Lincoln, North Dakota, 1875. Note the portraits of his two favorite generals—himself and McClellan—on the wall. The two antelopes and the snowy owl are overflows from his trophy room (he did his own taxidermy). Custer always made Libbie sit with him while he wrote his articles.