Creation (30 page)

Authors: Katherine Govier

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #FIC000000, #FIC019000, #FIC014000, #FIC041000

A

UDUBON TWISTS IN HIS TENT

. It is not himself as bird that he imagines, but the bird as himself. As a man. Sometimes, too, as a woman.

He is a monk, a disciple of birds. A captive to his Work, he cannot free the truest part of himself, a man’s passion to follow what he loves, to live that love throughout his whole body. He is caught in the yoke, the trap his species has devised to train, to thwart his desires — he is married, a father, a debtor, a working man who must sell his labours so that he and his family can live. There seems to him to be no solution, no flight.

He is full of awareness of his sins against the very creatures he worships. He has stalked birds. He has got them in his sights and shot them, reached for the fallen bodies in the bent grass. He has sometimes caught birds in his bare hands and squeezed the life out of them, careful not to spoil their feathers. He has killed so many. He has wired their wings and mounted them on boards; he has tamed them, which is sometimes worse. He tells himself this is part of love’s labour: to know birds. Even tonight, he will truss their corpses, and store their skins in oils and alcohol to be sent abroad.

He wonders if he loves birds so much as he envies them. But why envy a bird? He knows too well their strange reptilian nature, and their immense indifference, their hard struggle to survive, which is like his own. But does he envy the bird because it is free of doubt? A bird is without shame, but he, the portrayer of birds, is filled with shame.

Birds are his passion. He is violent with the subject of his passion; it is true; love

is

violent. But he fears he has gone too far. The birds which have filled his life are deserting him.

A

t rosy dawn on July 22, Captain Bayfield and Lieutenants Bowen and Collins in the two open boats pass out between the islands and Gros Mécatina Point, which they have located, now, to the south and east of their camp. They make a sombre sight, these launches, each with seven men at oar, each with a spotter seated in the bow with his cap on. They have taken leave of Audubon and the

Ripley

’s crew: a sturdy salute from the deck suffices this early morning. They have gone as far to the northeast as Bayfield planned, and now will make their way back down the coast, to reboard the

Gulnare

.

They discover the sea to be enormous; each boat loses sight of the other in the valleys between the peaks of water, loses sight even of the tops of the inland mountains. They are in the troughs of water as much as on the surface of it. But eventually, it calms. The waves flatten out and the whole surround of hundreds and hundreds of little granite islets and outcrops is revealed. They reach the harbour of Petit Mécatina where, suddenly, they can see right to the sandy bottom.

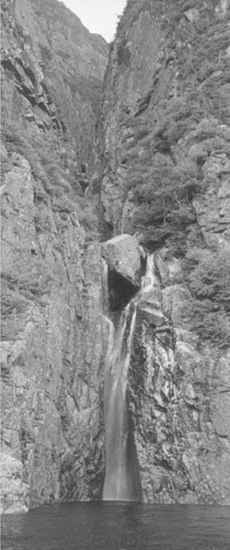

Running up sails in the favourable wind, they pass the falls at the Étamamiou River. From its fifty-foot drop the water boils and foams in a clear, deep basin. They pull their boats up against the shore. Had this been the South Pacific, they would have stripped down and bathed. As no doubt James Cook is even now doing, remarks Bowen. They decide to dip in at the edge anyway. The water is so cold it scalds and thrills their skin and makes their bones ache.

Anaesthetized from cold, they do not feel the moschettoes bite. The captain and the lieutenants become silly. (It does not seem odd to

them to continue to address one another in the formal way; the habits of years are unbreakable.) They make a war of it, themselves against the countless barbarian biting insects. The crew is cheered and works harder at the oars.

Bayfield recognizes that some note of high seriousness has gone out of his endeavour. He has left the dark vision of the

Granicus

by the dead coals of the fire he shared with Audubon. He has lightened himself by his confession. There is an atmosphere almost of celebration: he has conceived of defeat, but has not chosen it. He is now heading in the direction of the

Gulnare

, home. They will go north again in the vessel and do what they can do. He will finish, but his charts will be imperfect. He will forgive himself for that. Which shocks him and eases him. He is able to laugh when the sailors sing their rude songs.

Sally Brown’s a bright mulatter

She drinks rum and chaws terbaccer

For a time he has accepted his limitations, which is why he will always blame himself for what happens next.

I

T IS THEIR SECOND DAY OUT

. They are in a small cove in which they will hide for the night from the wind, which has swung east. The best way is to pull the boats right up on the rocks. They approach too quickly a rock with a good slant on it, and Collins jumps over the bow to shore. He turns to fend off, pushing the bow out with his arms, but the boat is coming in fast on a wave and slams into his chest. His feet lose their grip on the sloping wet granite. He slides as the boat rocks back and then, as it surges forward, tries to regain his feet. The sharp edge of the bow connects with his chin with a sickening crunch, his neck snaps back, he goes limp and slips like a fish below the hull.

Bayfield, standing midway back, watches Collins’s bony work-toughened hands, which have been gripping the gunwale, go limp and drop out of sight. It is a sight he will never forget.

“We’ve put him under the keel,” a sailor shouts.

“…

the water boils and foams in a clear, deep basin

.”

Two men jump off the other side and peer down. They can’t see him.

“Push us off,” commands Bayfield. He takes an oar and tries to pry the boat off the rock. But they have been hoisted forward and the launch is now heavy. More sailors jump out to follow his orders, and push the launch off.

Now he is alone in the launch and can’t get out. And Collins must be right underneath him. Shouting now, with ropes they pull the

Owen

sideways and up on the rocks. Bayfield jumps out. All seven men probe the water with their oars. The water is — Bayfield can estimate the temperature because he measures it daily — about thirty-nine degrees. Collins, even without a broken neck, will be in shock and not thinking clearly.

“He’s got to be under the hull,” Bayfield says, lying on his face on the rock and sweeping the bottom of the boat with his oar. But he encounters nothing and nor do the others, several of whom want to dive for their comrade.

Bayfield allows them, with a warning; they have only a minute or two before they will lose their reason because of the cold. The divers discover that the slope drops off quickly and that this rock is a lip. Under it the even colder water surges. The mystery disappearance must be accounted for by this; Collins has been forced under the lip of the rock and caught there by incoming waves. Bayfield sets his stopwatch. Several sailors go in for a minute or two at a time and come out to warm up: they cannot find Collins.

“It cannot be that a man is knocked in the chin by the

Owen

and simply disappears! We must find him.”

The search becomes increasingly grim and frustrated.

“He can’t have gone anywhere.”

“We’re running out of time.”

Bayfield looks at his stopwatch — ten minutes thirty seconds. They are, in fact, out of time. The man is dead. Those sailors who are not in and out of the water take to calling his name, as if he’d walked away for a minute, as if he could be roused by voice. By now the other launch comes into the bay and Bowen hears the news.

“He can’t be gone.”

“It’s as if he was snatched away.”

“He was just here.”

“Find him,” says Bayfield.

An hour later, they do. The body is caught under the ledge a few feet out from where the

Owen

has been hauled. Collins has a broken neck and is quite dead.

O

UAPITAGONE

,

JULY

25, 13

MINUTES AFTER

5

P.M

.

Had the pleasure of completing the Survey between Ouapitagone and Mécatina, a distance of 150 nautical miles never before Surveyed. Gave the Boat’s crew a glass of grog and then rowed onboard the

Gulnare

through a squall of wind and rain.

—

Surveying Journals

, Henry Wolsey Bayfield, Captain, Royal Navy

B

AYFIELD GAZES AT THE GULNARE HERSELF

. Her pretty neck and breasts brave the squall as they have braved so many others, and he feels a hot pressure in his throat at the sight of her pale full shoulders. Sometimes a figurehead will swell and split, but he is careful to keep her oiled. Sometimes a schooner will lose her figurehead in a storm; this too he is determined will never happen.

He walks from bowsprit to stern inspecting his vessel. She is in fine form, needing only a swabbing and some oil on the wood, and

some splicing of ropes. He sets the men to work on her and enjoys the sight of their energetic action in all her corners and joins.

Kelly greets them with open arms but with worry creases across his plump forehead. The mainspring of chronometer 741 has broken, and another one, number 546, has ceased to work for no reason he can understand. Bayfield fixes 546, which simply suffered from a loose screw, but 741 has died of old age and is a loss to the cause.

Collins is with them, wrapped in a sail. There is no earth in which to dig a grave. He must be buried in the deep, a practice Bayfield abhors. The water is so restless, a dreadful place to be laid. Although he does not fear death, he fears burial at sea. He saw it often enough in his youth; men were lost from time to time. But it has never happened under his command.

They have the service offshore, and consign Collins’s body where the water is deep. The men are angry again; it takes little to bring it out. Why did they sign on, he thinks, when they knew there would be no share of any profits? He may have to promise them a reward if they complete the portion of the survey he planned. During the dogwatch Bayfield hears the lame coxswain swearing. Although it is not Saturday he retreats to his cabin and brings out the miniature portrait of Mrs. Bayfield of Bayfield Hall. He places her on the ledge and paces back and forth before her.

“A man is often lost on a long sea voyage,” he explains. “There is nothing that could have been done. It was a freak accident.”

“I hope you don’t consider that your excuse,” says his mother.

“Never,” he says. “There is no excuse.”

He wants to tell her that he is lonely. But he cannot.

“You must carry on, Henry,” says Mrs. Bayfield. “I gave birth to you not knowing you would venture to these hostile climes. But since you have gone there, you must prevail. I would not have a quitter as my son.”

“Of course, I will carry on. It is only a question of how.”

“Quickly,” says Mrs. Bayfield. “And without explanations.”

When dark falls Bayfield finds himself in the bow, with his arm on the neck of the Gulnare herself. She is more comforting than his mother.

B

AYFIELD AND HIS SILENT CREW

venture on the next leg of the survey, making their way back up to Mécatina Harbour in the

Gulnare

, testing their own work. It is all good and the schooner flies without incident along the channel they have marked. From Mécatina they continue to beat their way up the coast, passing the mouth of the St. Augustine River, the great migratory route of the Montagnais Indians. They stop to trade biscuits for moccasins. There have been bad years for game, and the men and women are gaunt, their small children listless.