Creation (34 page)

Authors: Katherine Govier

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #FIC000000, #FIC019000, #FIC014000, #FIC041000

He comes upon this phrase:

“Pluming themselves, the gorged Pelicans patiently await the return of hunger.”

He stops over this notion: that the birds, driven only by their creature needs, should be sated, stop and stand motionless; “as if by sympathy, all in succession open their long and broad mandibles, yawning lazily and ludicrously.” At dusk, Audubon has written, hunger returns to reanimate them.

He wonders if this can be true. If Audubon actually saw it, or if, in his story-telling, he has invented the scene. It is a wonderful notion, to the diligent Havell, confined to his London shop, that creatures live only to gratify their immense desires.

Await the return of hunger

. He envies the bird.

“

He never lets the flame stand still, as it would burn the wax

.”

N

OW THAT THE COPPER PLATE

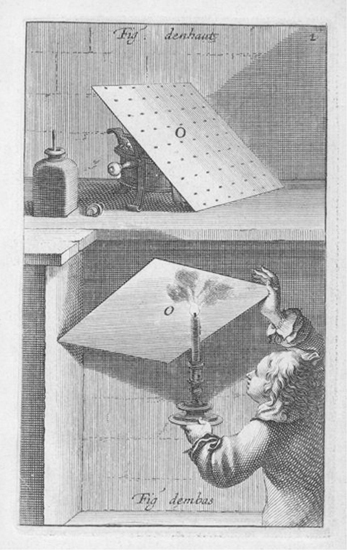

is ready, Havell has choices as to how he will transfer the watercolour image to it.

He could trace the original on thin paper with lead pencil, and then wet the back of the tracing paper with a sponge, putting its face to the etching ground. Then he could run the plate through his press to get an impression of the original.

Or he might trace the painting with a quill pen and India ink onto tissue paper oiled with linseed and then fix this tracing against the plate. Having done that, he would take a chalked paper, first brushing all the excess dust off it with a feather, and lay it on the plate, fold the ink version of the drawing over and trace all the lines again, leaving outlines on the plate.

But these tracing methods will leave the drawing reversed. The pelican will be looking to the viewer’s right, not his left. Havell is certain this would be wrong.

He could copy the pelican by eye, using a grid. And this is what he finally does, confident he will create an exact replica of the original. If he makes a mistake he can varnish it over with a camel’s hair pencil dipped in stopping varnish, wait ten minutes, and begin again. He will enjoy the process, a pleasure marred only by the fact that, since Audubon is insisting on more plates, and quicker, he will have to rush.

The etching itself is simple: he uses the needle as he would a pencil and cuts into the copper only lightly, keeping all his lines the same depth. The acid for the aquatint will make the lines deeper. When he has finished drawing, or redrawing, the bird, Havell adds the background.

He sets about to make the wall of wax. He takes an earthen pot half full of water on the fire and puts some wax into the water. He warms it over the fire until, testing it against the skin inside his wrist, he finds it is the temperature of new milk.

He likes this feeling. New milk brings good memories to his mind. When he himself was in the wild (at least the wilds of Monmouthshire), when he had run away from his father’s prohibitions and expectations, he would stop by farms and ask for breakfast. The farmer would bring him a cup of milk, foaming, still fresh from the barn. He recalls his luxuriant young man’s loneliness. The bolstering kindness from a

stranger’s hands, morning after morning, as he formed the will to prove his father wrong. He would be an artist.

And he

is

an artist.

He takes the wax into his hands and makes it into a long, flat strip. He warms one edge of this again, and presses it around the border of the plate, making a protective wall to keep the wash in, using his finger, which he wets in the water to make certain the wax sticks to the plate.

V

ICTOR STANDS BESIDE HIM

with a leather bag full of papers pertaining to the finances, and a vertical pleat between his eyebrows.

Havell wipes his hands on his apron and comes forward.

“Good day, Victor,” he says to the quiet young man. “I shall be with you in a moment.” He is just ready to do the first biting: this is for the farthest point in the distance in the landscape, the high canopy of trees where the last bit of light is leaving the sky. He retrieves the aqua fortis, which he has made by mixing spirits of nitre one part to four parts water, and pours it on the plate. It will sit for three minutes. He times it on his stopwatch, a gift from his uncle, the drawing master. After he sets the watch he looks up and smiles.

“Have you good news or bad?”

“Only this: Father says we must go more quickly. The institutions which have the first numbers are threatening to cancel because the early pages are wearing out before the later ones are produced!”

“I know what he wants. But I cannot go more quickly than this. In the first six years I worked for your father, I produced twenty-five plates a year; now I am producing fifty a year — that is one every week.”

“He says we must do better, faster,” repeats Victor helplessly.

“If he had money to pay for an assistant, I could.”

W

HEN THE ALLOTTED

time has passed, Havell stops out the lightest parts with varnish No. 1. He will let it dry for exactly half an hour. They go to the next room, where the colourists are working. On their easels are prints of the Yellow-crowned Night-Heron.

With Victor beside him, Havell walks down the rows. There are, at present, thirty-six colourists. They are the poor; some elderly men, a few women and boys. He does not pay them enough; he cannot. It is Audubon who has to make the payroll every week and when he is in the wilds Victor collects the dues from the wealthy subscribers. It is very simple. When Nathan Mayer Rothschild does not pay his bill, these people do not eat. When Stewart died, the former head colourist and a genius of sorts, Havell saw him buried in a pauper’s grave and had only a pound to give to his wife and child. This is perhaps why his father wished him to take up the law.

Once, he had Audubon go to the slums to deliver some money owing to the ginger-haired woman behind whom he now stands. Audubon was appalled to see the barricaded alley she called her rooms, and to see her send her younger children out to work. “What do they work at?” he asked, for the children were under six years old.

“They beg,” said the mother.

“I cannot bear to be in London,” Audubon announced when he returned. “This is why I would live amongst the birds.”

But there is no answer for it. The colourists are paid all the profession will bear. They have work in this shop only because Havell promised to produce for less than anyone else. As much as Audubon’s compassion runs deep, his desire to create

The Birds

runs deeper. When the colouring is poor, the subscribers complain. When they complain, they cancel. Audubon gets angry, and someone loses her job. Now Havell himself supervises; there will be no more complaints.

He looks over the shoulder of the ginger-haired woman. Her hand trembles slightly; he feels the tension in her shoulders as she tries to control it. She is frightened; her very life depends on this.

“Let me show you what I want,” Havell says gently to the woman. And he leaves the room, to return with the original. “Do you see how the male in full summer dress has such distinct lines of white and black over his eyes? We must make those lines stand out.”

“The paint is thin, sir,” she says. “I can do more layers but it sinks into the paper.”

“You are right. So why not use gouache? The lead will keep the colour on the surface.” He steps away to get a tube, passing another woman, to whom he says kindly, “That is lovely work, Clara.”

At the end of the line is a child who is working on the similac vine, which is twined around the branch of the dead tree the two Herons perch in.

“Green, more green,” Havell says. “You must paint five or six layers to make it truly vibrant. And stay within the lines!”

“But I gets dizzy, they winds so,” the child says.

Havell laughs. He nearly became lost himself while etching the vine as it wraps the branch.

“The botanical bit has been supplied by Miss Martin,” murmurs Havell to Victor. “I am told I shall receive more botanical illustrations from her. And I am to send her some paper, the Whatman Turkey, the same that he uses himself.”

Neither man has never met the highly controversial Maria Martin. But Havell feels a certain kinship to her. He has copied her blossoms, her butterflies, her luna moth, her peacock butterfly. He enters her imagination when he does so, as much as he enters Audubon’s imagination when he does the birds. They are very different places.

“Ah yes,” Victor says politely. “She is rather good.” But more importantly, there is some extraordinary sympathy between his father and the woman. Victor feels the energy and resents it. If not Maria herself, then a version of her is familiar to him as an aspect of his father’s behavior; he has long been his mother’s confidant.

The boy’s green gets greener. “Fine, fine,” Havell says.

“Miss Martin’s leaves are lovely,” says Victor grudgingly.

“Yes,” says Havell. Her vines curl and cling. Her leaves have sumptuous waving movements. They are not as bold as the birds but they are insistent, and sensuous; they have a green life to them, which seems to him female and unstoppable and which in his mind has become equally a part of this new world, America, with its rainbow of birds.

“Tell me, in truth,” says Havell to Victor, “do these creatures actually live in America?”

He is being seduced by the place.

H

AVELL HURRIES

back to his plate. Finding it dry, he applies the aqua fortis for the second biting. This will be the middle distance, the waters of the swamp as they wind backward. The second biting is on for seven minutes and then stopped and dried, and then he does the near distance. He leaves this on for twelve minutes. Then he stops and dries it.

Throughout this procedure, Victor speaks of some attack on his father that has been launched in a scientific journal. Another scandal threatens to erupt: it has been discovered that certain of the bird skins his father has submitted to the establishments are not genuine, but have been doctored with horsehair. He believes this hoax to have been played by an enemy, a young boy who once worked for Audubon. He seeks Havell’s advice, as one who is familiar with the learned artistic circles of England.

Havell gives a sympathetic ear. Not long ago he was a young man who quarrelled with his father and went, sketchbook in hand, to the River Wye to ramble and paint the medieval ruins. He was happy then in a strange, wounded way, and the woods and the crumbling constructions of stone were a refuge against the world. He was away and had chosen to be away and a passionate hurt and attachment gave power to his watercolours. He is half tempted to tell the young man he should run away to find himself, but, mindful of the need for everyone to pull together on the massive work, he stays silent.

The etching finished, he puts the plate back on the fire. When the wax wall has softened he pulls it off and, as the etching ground melts, washes it off with turpentine. He now has to clean the plate. He does this by rubbing oil on it. Others would have the boys do it but he insists on doing it himself. The plate must not be scratched. When he is satisfied that it is clean he brushes it, then wipes off the wet with a clean cloth and dries it very carefully.

The truth is, he likes to put his hands on the warmth of it, the silky clean copper, the thick blue-black ink. He imagines himself a cook, mixing substances to the right consistency. The hard labour combines with these sensory pleasures to tire him, heat him up, leave him dirty and exhilarated by the end of the day.

Now that it is ready for grounding, he stands the plate on a slant in a tin pan and pours the ground over it so that it runs down. When the ground has all run into the pan he turns the plate end to end and pours the ground back the other way. It settles finest on the part where the sky is to be. He sets the plate nearly flat on a table and wipes off extra grains from the bottom.

This is the very difficult part, and depends much on the weather. If the day is too cold the ground will run all over the plate and show no breaks. He has to heat the workshop with a stove then, which adds to the cost. If the day is too hot, the ground will behave in the same way. Today the temperature is perfect, mild.

“He sent me another stinging letter,” Victors says, apropos of nothing.

“He did? Of what did he complain?”

“That I must pursue subscriptions more avidly, that I have not sent certain guns and gifts to people he named, that I have not hurried you enough.”

“You must not mind,” says Havell. “He expects a great deal of you, and you are young. He is on fire to finish his book.”

“But I do mind.”

“Ah, fathers. I had this difficulty with my own. I tried to escape him, but I bore the name; what could I do?” They have been over this territory before.

“Exactly,” cries Victor. “How much must my name determine?”

“Everything is in a name and one cannot escape it.”

“I disagree. A name is entirely arbitrary,” says Victor crossly. “I was never good enough for him, anyway.”

“I think it may be exactly the opposite,” says Havell. “A father always wants his son to be better than he, but only in what he is not.”

“The name has eaten my life,” says Victor. “This is not what I wanted.”