Criminal That I Am (23 page)

Read Criminal That I Am Online

Authors: Jennifer Ridha

A. Yes, sir.

Q. As a matter of fact, after you were sent to Pennsylvania, didn't she continue to visit you there?

A. Yes, sir.

*

Q. You were able to manipulate her, isn't that right?

A. I just, I asked her. I didn't, I didn't convince her.

Q. Well, she just, it was like, Oh, that would be a great idea, I'll do it? Is that what you're trying to tell us?

MR. ANDERSON: Objection.

THE COURT: Sustained.

Q. You manipulated her in such a way that she did something that was a crime?

MR. ANDERSON: Objection.

THE COURT: Overruled.

A. No, I just asked her.

Q. And she just agreed, right? Right away?

A. I certainly didn't press her to do it.

*

Q. As a matter of fact, sometimes you don't know what's truth and what's fantasy, correct?

A. No, I think I know the difference between truth and fantasy.

Q. But you do lie, correct?

A. I try not to.

Q. And you tell lies to accomplish something you want for your own selfish self, correct?

A. No, I wouldn't agree with that.

Q. So the incident with the lawyer, that isn't something that you did to help yourself, is that what you are saying?

A. There was no lying or dishonesty involved in that.

Q. So if you expressed feelings of affection towards her, that was the truth? You felt that way about her, is that correct?

A. That's correct.

*

Q. Tell us what you told her to do.

A. She was involved in trying to get the medication for me throughâ

Q. Did you hear my question? Listen to my question.

THE COURT: He's answering your question. You may not like the answer, but he's answering your question.

Q. I'm asking, tell us what you told her to do with respect to smuggling in drugs?

A. I asked her to put Xanax in a balloon and to give it to me during our lawyer visits. That is what I asked her to do.

*

Q. Where did you tell her to put the balloon with the drugs?

A. I didn't specify anything specific on that.

Q. Where did she put it?

A. I don't know, sir. I don't remember.

*

Q. Well, she gave it to you, didn't she?

A. Yes.

Q. You were in a room where attorneys meet with their clients?

A. Right.

*

Q. She took it out from some part of her body, didn't she?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You know so, don't you?

A. Yes, sir.

*

Q. Did she take it out of one of her body orifices?

Do you know what that means?

A. I do. No, I believe from what I can remember I believe she took it out of, I saw her take it out of her bra.

I

hear a sound from the living room that is familiar and disquieting. I am in my bedroom, ignoring it. I have just hung up with my lawyer, whose associate has been sitting in the courtroom watching Cameron's testimony unfold. He has been using the courthouse pay phone to update my lawyer, who in turn has been updating me.

When my attorney relays to me Cameron's testimony I politely explain to him that his associate must not have been hearing Cameron right. There is no way Cameron would share the medication that he so badly needed, I say. How is it that his visible symptoms vanished? And what purpose could it serve him to disclose my identity? No, there is no way.

As to the mention of my undergarments, I am particularly incredulous. Why would he say this? I remind my attorney of how I placed the pills in a bag of pretzels before Cameron even arrived in the attorney room. I explain that nothing could possibly be served by my harboring something in my bra, that its underwire caused additional scrutiny, that I'm not even sure how one could remove something from a bra in an attorney room without partially undressing.

“There must be some misunderstanding,” I say. “That just can't be Cameron's testimony.”

My lawyer says nothing. I think I can hear him shrug.

It is a heavy slap to the face, learning that everything in Cameron's testimony is exactly as my lawyer has recounted it to be. I want to reconvene the jury and explain. Explain to them that today is the first time that I've learned that these pills were being distributed to others, that I was supplying currency to men whom I do not know but who somehow know me. That the pills that I brought for Cameron were prescribed for a condition that I personally observed him experience. That Cameron can't speak to how I brought in the pills. That the contortion involved in removing a balloon of pills from one's bra while seated in

a room with a glass door is beyond my physical capability. That due to the circumstances of our acquaintance, Cameron could not possibly see me take anything out of my bra, that he has never seen my bra, he has never seen anything at all that resides below my neck or above my knees.

That this has all gone so terribly wrong.

But the jury has been dismissed for the day. As I craft my explanation, they are probably at home eating dinner with their families, possibly, against the judge's orders, mentioning in passing the events of the day, about the celebrity drug dealer, about his attorney accomplice, about said attorney's underthings.

It is too late.

But correcting my attorney, reconvening the jury, these are just sideshows. Underneath my disbelief and defensiveness is the crushing realization that I have been betrayed. Cameron did not only break his promises about keeping his mouth shut, taking the fall. He did not only lie and mislead. He actively, willingly, placed me directly in harm's way. But even this is not the worst part. No, the worst part is me. I had taken an inordinate risk on behalf of someone who clearly did not care what happened to me. No, wait, that isn't the worst part. The worst part is that I acted out of love for someone who could not possibly have loved me in return. Nope, there is something still worse. The absolute worst part of all of this is that the entirety of what transpired has been captured by a court reporter. My love-starved stupidity is recorded in history.

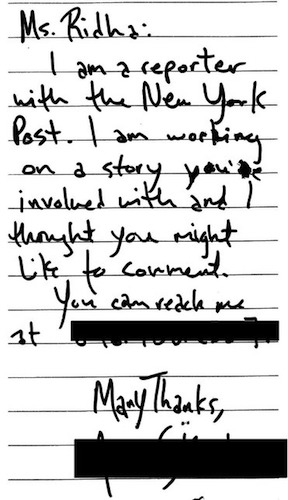

The sound from the living room has grown loud enough to shake me from my thoughts. As I make my way into the living room, I immediately place it: the doorbell is ringing. Over and over and over again, in a manner not unlike that employed by Burly Man so many months before, the rapid presses composing an uninterrupted siren.

This can mean only one thing. And so I freeze. I stop so abruptly that I grab onto a piece of furniture for balance, knocking over a pile of books and papers on a nearby end table. They crash to the ground.

As soon as they do, the ringing stops. I hear movement on the other side of the door, as though the person behind it is deciding her next

move. She knows that I'm inside, and I know that she's outside, but neither of us says a word.

I remain completely still. I am breathing so loudly I think she might hear.

Suddenly, the stranger begins ringing the bells of all of my surrounding neighbors, all of them elderly, each of them easy to scare. I can hear the symphony of bells through my door. She seems to be making a ruckus in the hopes that it will rouse me from my apartment.

The stranger does not know me, does not know that I am fully capable of cowardice when it serves my own interests. And so, while I feel awful for their intrusion, I selfishly remain where I am. It continues for several moments. Finally, a door opens. I can hear her demanding of my neighbor Rosie where I might be.

“I don't think she's at home.” Rosie trembles. “Otherwise she would open the door.”

“Well, do you know when she'll be back?”

“I'm sure she'll be home later today,” Rosie says obliquely. “Maybe you can leave her a note.”

The stranger is silent for a moment. Then she thanks Rosie and says that she will.

I continue to remain within earshot of the door, careful not to make a sound. I see a small piece of paper slip under the door. I hear Rosie's door close.

I wait for a moment. It is silent.

I start to take a deep breath, thinking that this is over. But as soon as I start to relax, my body stiffens at a thought.

The elevator did not make a sound. The stranger must still be outside my door.

I don't wait to see how long she remains. I quietly tiptoe to my bedroom. I will not return to my living room for two days. And by that time, everything that is going to happen will have already happened.

T

he phone keeps ringing. I avoid answering it. Dizzy with the discoveries of the day, I feel that there is little else that I need to know.

When I finally call my attorney back, he reports that the

New York Post

has discovered who I am and has asked for his comment.

“I know,” I tell him. “A reporter was at my door.”

“Okay. Maybe don't leave the apartment tonight.”

I feel a surprising rush of silent anger at his well-meaning but obvious advice. I sort of hate my attorney right now. He has been my hero for fifteen months, but in this moment I can't stand him. Although I can follow the course of events that have led me here, I feel he was

somehow supposed to protect me from this. As comforting as it is to feel you have someone looking out for you, it's just as troubling when you realize that he is not invincible.

I wonder if my clients ever hated me in this way, too. If they did, they were right to hate me. The right to hate your lawyer should be set forth in the New York Statement of Client Rights, alongside the right to have your phone calls returned and your bills itemized.

“How did they get your address, do you think?” he asks.

“It's public because I gave money to Obama in 2008,” I say. I sort of hate Obama right now, too.

“We are preparing a statement to give the

Post

,” he says. “I will send it to you so you canâ”

I cut him off. “Just say whatever you think is best.”

“All right.” I can tell that he wants to say something helpful, but there isn't anything helpful to say.

“Thanks,” I say, because that's all I can think to say to get off the phone.

He takes a breath, as though there is something more, and then thinks better of it. “I'll call you tomorrow,” he says helpfully.

“Yes, okay. Great,” I say.

We say good-bye, knowing that there is nothing great about any of this.

I

field a series of calls from friends and family, each of which makes me more agitated than the last. The words of comfort are sincere, but I don't want to be comforted. I want this to not have happened. Why is everyone telling me I'll get through this, as though all of this is reasonable or expected? And why is everyone acting as though they could possibly understand?

The only words that break through are from, of all people, my usually disapproving mother. I've warned her that what's coming is going to very possibly be an assault on her traditional sensibilities. But in this moment, perhaps because I'm already so upset, she does not display the expected concern.

Instead, she says, “Jennie, your father and I adore you. We always will.”

And for some reason, these words are a cold compress on my stinging face. I let go of the anger and find that underneath there is sad resignation.

I start to cry. Not because I am moved by a proclamation of my parents' love or even overwhelmed at the reminder that I have it. I cry because I suspect that after tomorrow is over, it is all that will remain.

WEDNESDAY

I awake after a fitful night of sleep. It is still dark outside.

I find it a curious thing, anticipating publication of something terrible that you've done. When I committed my crimes, I always presumed they would remain in the place where one's darkest secrets are normally stored, revealed only under threat of torture or maybe on a deathbed. I did not think that my worst moments would be put in print.

I look out the window. The sky has now shifted to a deep blue, the sun is about to cast its light on a new day.

Whatever there is to be said about my crimes has already been written, is already available at the newsstand, already sitting on the doorsteps of the paper's half a million subscribers. I look at my laptop, still at the foot of my bed from the night before, knowing that the story is inside.

I look out at the sky one last time before I open my laptop. I am painfully aware that these are the last moments; this is the beautiful before that becomes the ugly after. And so I enjoy the sunrise for one more minute, knowing that by the time it returns, everything will be different.

H

ere is the headline:

DRUGS IN BRA.

This is already not good. It does not get better.

Cameron is described as having taken the stand against his drug supplier, as looking like a “scruffy and tattooed version of his father,” as having “romanced a defense lawyer who got busted for smuggling him pills in jail,” as having gotten “into a relationship with the woman while she represented him following his 2009 arrest for narcotics trafficking.