Cross Channel (11 page)

Authors: Julian Barnes

‘Those cannoneers, my dear. Had they but half the skill of Lumpy Stevens, they should have not wasted so much shot.’

‘That is quite true, Hamilton.’

Lumpy could hit a feather placed upon the ground one time out of four in practice bowling. More than one time out of four. He had won the bet for Tankerville at Chertsey. Lumpy had been the Earl’s gardener. How many of them now were buried in the soil?

‘Dorset was never again the same man,’ he continued, easing the remnants of his cutlet to the side of his plate. ‘He retired to Knole and received nobody.’ Sir Hamilton had it on authority that the Duke had kept to his room like an anchorite, and that his only pleasure was to hear the music of muted violins playing from the other side of his door.

‘I had heard that the family was disposed to melancholy.’

‘Dorset was always the liveliest fellow,’ the General replied. ‘Before.’ This was true; and at first he had remained so after his return from France. That autumn there had been cricketing as there had been all their lives. But as Knole filled with

émigrés

the situation in France had brought dark clouds to Dorset’s mind. There had been letters exchanged with Mrs Bourbon, and many considered the loss of that intimacy to be the immediate cause of his melancholia. It was repeated, not always in the warmest of spirits, that upon quitting Paris the Duke had made a gift of his cricket bat to Mrs Bourbon, and that the lady had preserved this attribute of British manliness in her closet, just as Dido had hung up the galligaskins of the departed Aeneas. The General did not know the particularities of this rumour. He knew only that Dorset had continued cricketing at Sevenoaks until the season’s end of 1791 - the very same summer in which Mrs Bourbon and her husband had undertaken their flight to Varennes. They had been recaptured, and Dorset had cricketed no more. This was all the General could say, except that Dorset, thinning the noise of the world to muted violins heard through a wooden door, had not lived to learn the murderous news of the 16th October 1793.

God knew he was no Papist, but the cannoneers and fusiliers of the revolutionary army were no Protestant gentlemen either. They had taken the crucifixes from the fields and

made an

auto-da-fé

of them. They had paraded asses and mules wearing the vestments of bishops. They had burnt prayer books and manuals of instruction. They had forced priests into marriage and ordered French men and French women to spit upon the image of Christ. They had taken their knives to altarpieces and their hammers to the heads of saints. They had dismantled the bells and taken them to foundries where they were cast into cannon with which to bombard fresh churches. They had expunged Christianity from the land, and what had been their reward? Buonaparte.

Buonaparte, war, famine, false dreams of conquest and the contempt of Europe. It grieved the General that this should be the case. He had many times been rallied by his fellow officers for being a Galloman. It was a fact he would acknowledge, and in honest justification would adduce evidence as to the national character such as he had observed it. But he also knew that the true source of his inclination lay much in the effects of memory. He judged it probable that all gentlemen of his age in some way loved themselves when young, and naturally extended such tenderness to the surrounding circumstances of their youth. For Sir Hamilton, this time had been that of his tour with Mr Hawkins. Now he had returned to France, but it was to a country changed and reduced. He had lost his youth: well, every living soul lost that. But he had also lost his England and his France. Did they expect him to endure that also? His mind had become a little more steady since they had permitted Evelina and Dobson to join him. Yet there were times when he knew what that poor devil Dorset felt, except that for him there was no door and the violins were not muted.

‘Dorset, Tankerville, Stevens, Bedster, myself, Dobson, Attfield, Fry, Etheridge, Edmeads …’

‘The lieutenant has procured for us a melon, my dear.’

‘Whom do I forget? Whom do I damned forget? Why is it always the same one?’ The General stared across at his wife, who was poised to carve - what? A cricket ball? A cannonball? The violins were scrabbling at his ears like insects. ‘Whom do I forget?’ He leaned forwards on his elbows, and covered his eyelids with his fattened finger-ends. Dobson quickly bent his head towards Lady Lindsay.

‘You forget Mr Wood, I believe, my dear,’ she murmured.

‘

Wood

.’ The General took his fingers from his eyes, smiled at his wife, and nodded as Dobson lowered a slice of orange melon before him. ‘Wood. He was not a Chertsey man?’

Lady Lindsay was unable to seek assistance with this enquiry, since her husband’s eyes were upon her. So she answered cautiously, ‘I have not heard so.’

‘No, Wood was never a Chertsey man. You are right, my dear. Let us forget him.’ The General dusted sugar on his melon. ‘He had never been in France, of course. Dorset, Tankerville, myself, that is all. Dobson, of course, has been in France subsequently. I wonder what they would have made of Lumpy Stevens?’

Lumpy Stevens had won Tankerville’s bet for him. Lumpy Stevens could hit a feather one time in four at practice-bowling. The French cannoneers …

‘Perhaps we may expect a letter tomorrow, my dear.’

‘A letter? From Mr Wood? I very much doubt that. Mr Wood is almost certainly cricketing with the Angel Gabriel at this very minute on the turf of the Elysian Fields. He must be dead and buried by now. They all must. Though Dobson is not, of course. No, Dobson is not.’ The General glanced up above his wife’s bonnet. Dobson was there, staring straight ahead, unhearing.

Dorset’s embassy in Paris had prospered. There had been complaints against him of the usual kind. Nowadays the world was ruled by Mrs Jack Heythrop and her sisters. But

The Times

had reported in 1787 that as a consequence of the Duke’s presence and example, racing in France had begun to decline, and the pursuit of cricket had begun to take its place, as making better use of the French turf. It had surprised the General that the young lieutenant who spied on them had been unaware of this, until, the calculation being done, it was shown that the fellow would scarcely have said farewell to his wet-nurse at the time.

The mob had burnt Dorset’s

hôtel

in Paris. They had burnt prayer books and manuals of instruction. What had become of Dorset’s cricket bat? Had they burnt that too? We were about to embark at Dover on the morning of the 10th when whom should we see but the Duke. On the quay, the mail packet at anchor behind him. In good spirits, too. Therefore we had gone to Bishopsbourne to dine with Sir Horace Mann, and the following day the match between Kent and Surrey …

‘Dorset, Tankerville, Stevens, Bedster, myself…’

The melon is sweet, do you not find?’

‘Dobson, Attfield, Fry, Etheridge, Edmeads …’

‘I think tomorrow we shall expect a letter.’

‘Whom do I forget? Whom do I forget?’

The physician, though French, had seemed a reasonable man to Lady Lindsay. He was a student and follower of Pinel. The melancholia in his view must not be permitted to develop into

démence

. The General must be offered diversions. He must go for walks as often as he could be persuaded. He was to be allowed no more than one glass of wine with his dinner. He must be reminded of pleasant moments from

the past. It had been the physician’s opinion that, despite the evident improvement in the General’s condition brought about by the presence of Madame, it might be advisable to send for the man Dobson, to whom the General made such frequent allusion that the doctor had at first taken him to be the patient’s son. It would be necessary, of course, to place a guard upon Sir Hamilton, but it would be as discreet as possible. It was regrettable that, according to the physician’s private information, there was no immediate prospect of the proposed exchange being effected, and of the Englishman returning to his own country. Unfortunately, it appeared that the family and advocates of General de Rauzan had repeatedly failed to persuade those close to the Emperor of the Frenchman’s military importance.

‘Whom do I forget?’

‘You forget Mr Wood.’

‘Mr Wood, I knew it. He was a Chertsey man, was he not?’

‘I am almost sure of it.’

‘He was, he was indeed a Chertsey man. A fine fellow, Wood.’

Normally he remembered Wood. It was Etheridge whom he forgot. Etheridge or Edmeads. Once he had forgotten himself. He had the other ten names but could not seize the eleventh. How could this happen, that a man forgets himself?

The General had risen to his feet, an empty wine glass in his hand. ‘My dear,’ he began, addressing his wife but looking at Dobson, ‘when I reflect upon the terrible history of this country, which I myself first visited in the year of Our Lord 1774 …’

‘The melon,’ said his wife lightly.

‘… and which, since that time, has suffered so much

travail. There is a certain conclusion which I should like to venture …’

No, it must be averted. It was never beneficial. At first she had smiled at the reflection, but it led to melancholia, always to melancholia.

‘Do you require more of this melon, Hamilton?’ she asked in a forceful voice.

‘It appears to me that the terrible events of that terrible year, of all those terrible years, which placed our two countries so far apart from one another, which led to this terrible war, such events might have been avoided, indeed could have been avoided by something which on first examination you might judge a mere fancy …’

‘Hamilton!’ The wife had risen in her turn, but the husband still gazed beyond her at the impassive Dobson. ‘

Hamilton

!’ When he continued not to hear her, she took her wine glass and cast it on to the terrace.

The screeching violins ceased. The General returned her gaze, and shyly sat down again. ‘Oh well, my dear,’ he said, ‘it was only an idle notion of mine. The melon is ripe, is it not? Shall we each have another slice?’

E

VERMORE

A

LL THE TIME

she carried them with her, in a bag knotted at the neck. She had bayoneted the polythene with a fork, so that condensation would not gather and begin to rot the frail card. She knew what happened when you covered seedlings in a flower-pot: damp came from nowhere to make its sudden climate. This had to be avoided. There had been so much wet back then, so much rain, churned mud and drowned horses. She did not mind it for herself. She minded it for them still, for all of them, back then.

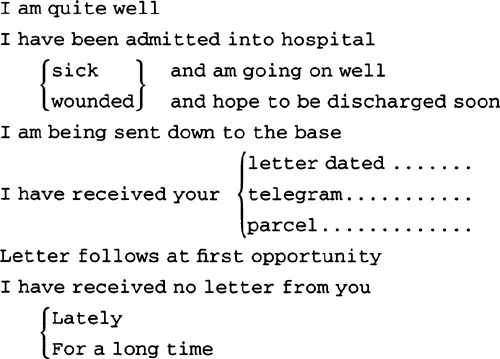

There were three postcards, the last he had sent. The earlier ones had been divided up, lost perhaps, but she had the last of them, his final evidence. On the day itself, she would unknot the bag and trace her eyes over the jerky pencilled address, the formal signature (initials and surname only), the obedient crossings-out. For many years she had ached at what the cards did not say; but nowadays she found something in their official impassivity which seemed proper, even if not consoling.

Of course she did not need actually to look at them, any more than she needed the photograph to recall his dark eyes, sticky-out ears, and the jaunty smile which agreed that the fun would be all over by Christmas. At any moment she could bring the three pieces of buff field-service card exactly to

mind. The dates: Dec 24, Jan 11, Jan 17, written in his own hand, and confirmed by the postmark which added the years: 16, 17, 17. ‘NOTHING is to be written on this side except the date and signature of the sender. Sentences not required may be erased.

If anything else is added the postcard will be destroyed.’

And then the brutal choices.

He was quite well on each occasion. He had never been admitted into hospital. He was not being sent down to the base. He had received a letter of a certain date. A letter would follow at the first opportunity. He had not received no letter. All done with thick pencilled crossing-out and a single date. Then, beside the instruction

Signature only,

the last signal from her brother. S. Moss. A large looping S with a circling full stop after it. Then Moss written without lifting from the card what she always imagined as a stub of pencil-end studiously licked.