Crossing the Borders of Time (43 page)

One day as Uncle Max took leave of her father, heading home to Havana after a visit, Janine caught up with him near the camp gates. She felt emboldened by having noticed him sneak out letters for Sigmar and Alice, who had been urgently writing to the American relatives of their old friend Meta Ellenbogen. Upset by rumors that their Freiburg tenant had been among those deported to Gurs, but was now being held in a transit camp near Marseille, they hoped her American cousins might swiftly gain her release by helping secure a visa and passage. So, Janine reasoned, if Uncle Max was willing to skirt Tiscornia’s rules and mail letters for Sigmar, perhaps he would mail her letter to Roland. Then she went further. Not only did she beg Max to post her letter to France, but she also gingerly ventured to ask to use his Havana address to receive a reply, since she could not receive any mail in the camp.

Monsieur Roland Arcieri, 27 rue Puits Gaillot, Lyon, France

. Max perused the envelope she handed to him, raised his eyebrows and studied her face.

“

Nur ein Freund, Onkel

,” she quickly assured him, only a friend. He said nothing, folding the letter into his pocket, where she hoped it would not become too wrinkled and sweat-stained before it reached the hand of her love. When she unexpectedly saw her letter again the following week, however, this time in the hands of her father, its crumpled condition was the least disturbing aspect about it. Uncle Max had opened the letter, read it, and furiously brought it straight back to Sigmar, whose dark eyes behind his bifocals popped with rage.

“

‘Erich comes here to see me, but he is the same foolish boy he always was!

’ ” Sigmar quoted the letter, her hurtful description and indiscretion having embarrassed him terribly in front of his friend, whose loyalty seemed a godsend in this odd, forgotten spot on the planet. “How could you let yourself write such a thing? What possessed you to risk letting Uncle Max read such a nasty comment about his own son? And after all of his care and kindness toward us!”

Sigmar punched at the air, tore the letter into a scattered puzzle of meaningless pieces, and totally sidestepped the propriety of Max’s violating Janine’s privacy by reading her mail. She silently fumed, not daring to speak. How could the man be so lacking in morals and pride as to admit to snooping and then bring back the letter to share with her father? The gall—imagine acting aggrieved and indignant instead of ashamed!

“As for Roland, you must forget him,” Sigmar asserted, somewhat more calmly. “

Fertig

,” finished. “There is no point even thinking about him.

Dummes Zeug

,” just stupid nonsense, he muttered. “He is not one of us. You can’t ignore that. The world doesn’t, either. There is a war and an ocean between you. Even if Erich is not the man you’re ready to marry, you will make a new life and meet many others when we get to America. But if you can’t be more careful, what with writing to France in the middle of war, you’ll get us locked up here forever! Don’t dare try something that foolish again. If the Cubans find out, they’ll think you’re a spy. And the next time you see Uncle Max, I expect you to apologize to him and make some excuses.”

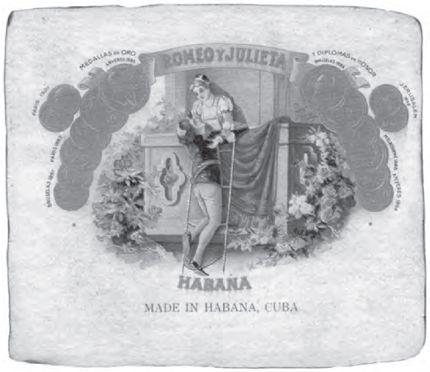

To soothe his nerves he pulled out his cigars, the single delight that coming to Cuba had thus far afforded, after years of enforced abstention from smoking. Dourly, Janine stared at the package. Sigmar termed his favorite cigars his “

Lieblinge

,” his darlings. How peculiar—Janine hadn’t really noticed before—that the brand was called Romeo y Julieta. Their names on the box were written on a pink ribbon above a picture of the romantic Shakespearean balcony scene. Roses and bougainvillea encircled the couple in a bower of blossoms, but their faces were already wearing tragedy’s masks. Juliet gazed with ineffable sadness and longing into the hopeful face of her lover as if she already knew their future was doomed.

The box cover of Sigmar’s favorite Romeo y Julieta Cuban cigars

Life in the camp proceeded that summer with no sign of release, and the refugees tried to organize constructive activities: morning exercise classes in the pergola; lessons in English (some taught by Norbert), Spanish, and Russian; school for the children and evening lectures. The Orthodox Jews also established a prayer room above the bodega to hold services, while in the shaded tranquillity of long afternoons, bearded men bent over tables outdoors to study the Talmud, a scene that created an image of peace and continuity for those who simply lingered to watch them. But with the boredom and unremitting heat of the summer, frustration lit fires beneath restive young people, impatient for ways to spice up confinement.

“

Lisel! Komm schnell!

I can’t wake up Norbert!” Sigmar came crying for Alice in alarm outside the women’s dormitory one morning, having woken to find their son unconscious. Norbert had joined a group of young men who broke into the clinic the previous evening to get drunk on rubbing alcohol, which just made them sick. Others channeled their energies more purposefully into organizing political action. Fritz Lamm, a Socialist activist, then thirty-one, whom Janine had met aboard ship, took to the soapbox to call on the young to stand up to the Cubans and militate for release, if for themselves only.

“The older generation has already lived their lives!” Janine would always remember his impassioned appeal. “Let the older ones stay and wait in the camp. We young must demand our freedom now to get on with our lives, or else we will have to take matters into our own hands! The time is now!”

When the outspoken utopian placed an inscription along with his picture in Janine’s autograph book, he addressed her in a similar vein. “Needless Fear!” he titled his page, writing in German with its capitalized nouns that seem to dress up the vaguest pronouncements with the dignified luster of aphorism. “No one can seize Freedom and Fortune from you as long as both lie within you, and both lie together with Hope and Memory.”

Many who gathered to hear Lamm’s orations admired his insistence on action, and, returning to Germany after the war, he would gain public attention as an idealistic social thinker. But within the camp there also were those who resented Lamm’s divisive proposal to demand freedom for just part of the group, giving rise to consternation among older inmates who did not appreciate being discounted.

This prompted Charles H. Jordan, the hardworking Joint representative in Havana, to send a special report to his New York office observing that the Tiscornia refugees were sunk in a “very depressed state of mind.” He added: “I am afraid that they are becoming very impatient and inclined to follow the leadership of some of the more aggressive people who believe that the policy of waiting for action on the part of the authorities should be changed for a policy of action on the part of the refugees themselves—which expresses itself, at this point, in internal incidents.”

While working for the detainees’ release, Jordan had been assiduously trying to better the conditions in camp, assisting with food and medical aid, and eventually persuading the Cubans at least to allow for the delivery of mail and money sent to the refugees in care of the Joint. On top of the inflated expenses of life in Tiscornia, the refugees were each expected to show a $500 bond and $150 in “continuation of voyage money” as a condition of winning release. An extremely high sum, for the Günzburger family of five, for example, it would translate to more than $45,000 today. While there were efforts afoot to get these requirements waived, the Joint simultaneously worked through the National Refugee Service in New York to contact the inmates’ American relatives and urge them to help out with loans.

In regard to Cuba, however, Joint officials pronounced themselves shocked and discouraged by what they viewed as “abnormal” indifference on the part of the local Jewish community, among them fifty American Jewish families, in the face of the troubles afflicting the refugees. They found the community of more than ten thousand local Jews disorganized, lacking in leadership, and uniquely tightfisted in response to pleas for philanthropic assistance. In a report tracing most Jewish settlement in Cuba to Eastern European refugees who had arrived in the 1920s, the Joint charged that although those immigrants had become financially successful on the island, they had failed to develop an appropriate sense of concern for the newcomers, many in need. “There is the perennial antagonism on the part of the East European Jew to the Western Jew,” the report explained, while “the American Jews as a whole seem to resent the refugees’ entrance to Cuba, and are not at all keen on helping, whether financially or otherwise.”

In an interview that September in

Havaner Leben

, Jordan spoke even more bluntly, declaring Havana “the only place in the world” where the local Jewish community had failed to help the Joint in its mission. “The local Jews who have lived here many years do not have any feeling about helping the refugees,” he said. “The Jews the whole world over, everywhere on the whole earth, know their duty, except the Jews in Cuba.”

The Joint went so far as to conclude that not only had wartime immigration turned into a “rich source of graft for Cuban government officials and employees,” but also that several members of the Havana Jewish community were themselves involved in these rackets, while the rest remained passive or wasted their energies in aimless infighting. With unproductive lay members, the Cuban branch of the Joint, founded five years earlier, depended almost entirely on Jordan himself. To help him negotiate with the government, Jordan therefore hired a prominent local attorney and politician, Jorge García Montes—later Cuba’s prime minister—and their combined endeavors achieved major improvements to the refugees’ lot.

Key among them was a change in the law that had required all refugees to renew their transit or tourist visas monthly, a difficult and costly process. Now all the Jews who had fled to Cuba to escape Hitler’s Europe gained resident status valid until the end of the war. This effectively stopped the graft in the Immigration Department that was bilking them tens of thousands of dollars per year in fees and bribes just for the right to renew their expiring visas every thirty days. With this guaranteed stability, those refugees who had arrived in Havana somewhat earlier and were living in the city could find jobs.

A more challenging problem involved the special situation of the three thousand five hundred German and Austrian Jews whom the Cubans regarded with extra distrust. Like those German Jews who had sought safety in France before the outbreak of war in 1940, only to be slapped in French prisons under suspicion of being Nazi spies, these refugees found their allegiances questioned. Even before the

San Thomé

landed, the Joint planned to persuade President Batista to certify the German and Austrian refugees as “loyal aliens,” based on a careful review of their individual credentials and backgrounds. Toward this end, according to a confidential Joint report, García Montes sent the Cuban State Department a “memorandum detailing the persecution of the refugees, their denaturalization by the German government, and the actual feeling of the refugees toward the totalitarian countries.”

The consulates representing the other nations whose refugees were interned in the camp had sent officials to see their former citizens and seemed prepared to offer them the moral guarantees the Cubans required as another precondition, besides money, for winning release. The American consulate in Havana, as well as other American and Cuban government agencies, had investigated all the passengers, but detainees from Germany and Austria had no way to obtain the requisite moral stamp of approval. On July 19, grappling with their lack of a consulate to vouch for them, eleven German men in Tiscornia, Sigmar among them, hit upon the idea of enlisting support instead from the international fraternal order of the B’nai B’rith. In desperation, they wrote via the Joint in Havana to the

Grossloge

or grand lodge in New York, beseeching the B’nai B’rith—like a government of a people dispersed—to provide the character references the Cubans demanded.

No longer citizens of any country, they wrote as “international brothers” and offered the only credentials they had: their former faithful membership in the German lodges of the B’nai B’rith based in the cities where they had lived. And so they listed themselves, each former German reduced to identifying himself through a lodge now destroyed in a city where he no longer belonged: Sigmar Günzburger of the Breisgau Loge in Freiburg, Otto Nussbaum of the Kaiser Wilhelm Loge in Bremen, Alfred Kahn of the Carl Friedrich Loge in Karlsruhe, and so on, all of the men, from Plauen and Stuttgart, Augsburg and Saarbrücken, where going to meetings of the B’nai B’rith had been part of their roles as upstanding Jewish community leaders. They explained their arrival in Cuba on the

Guinée

and the

San Thomé

and pleaded for help in winning release from the “bitter torture” of a continued detention behind barbed wire, an imprisonment they did not understand after so many years of suffering under Hitler’s oppression.