Crossing the Borders of Time (44 page)

“

Warum wir hier sein müssen, wissen wir nicht

,” they wrote. Why we must be here, we do not know.… “While the refugees of other countries have the protection of their consulates, we feel completely abandoned. It would be an enormous relief for us lodge brothers—who in better days always tried to help others—if our American brethren would take some interest in us. Please let us know quickly that we can depend on you.”

The B’nai B’rith could do little more than forward the letter to the Joint’s New York office. On October 6, a Joint official also updated headquarters on the situation, which by then had dragged on for more than five months. Cuba was about to begin releasing those who qualified, insofar as they would not become a financial burden to the country and they could present official guarantees of their moral and political backgrounds.

“The passengers of the [

San

]

Thomé

have been investigated by the American consulate in Havana as well as by other agencies of our and Cuba’s government. To the best of our knowledge, all of these are unobjectionable and loyal to the cause of the United Nations,” wrote Robert Pilpel, a top Joint official. “Those who are nationals of the United Nations countries, Poland, Russia, Czechoslovakia, Luxembourg, Belgium, as well as the Swiss and French, number about half those in Tiscornia, the balance being made up of some Austrians and for the most part, Germans. After all these months, the reasons for their extremely prolonged detention remain unclear and ununderstandable. Only now is there a prospect for the release of some whose consulates in Havana are prepared to give a moral guarantee.”

Those without consular representation in Havana could face problems, he noted, especially the German Jews, deemed stateless as a result of having been denationalized by German government decree on November 25, 1941.

The High Holidays passed that fall without the buoyant sense of spiritual cleansing and rededication that Janine and others had hoped to recapture in a new world. Prayers for forgiveness of sins, for peace and redemption failed to lighten the hearts of the people whose vision of escaping from Europe had never included hard months of detention. They searched their souls and past behavior, prayed for the blessing of purposeful lives, and extolled the burden of chosenness as if generations had not already paid everything for it.

On Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, Janine observed the obligation to fast. But in the parching heat of Cuba’s September sun, her craving for water became so intense that in brushing her teeth in the communal bathroom that morning, she permitted a drop to slide down her throat before she piously spit out the rest. Guiltily, she cast around to see if anyone noticed. But the One who counted, she knew, saw everything. She told herself that her indulgence had been an accident only, yet knew in her heart she had done it on purpose and that punishment was inevitable—especially as camp doctors had warned against drinking tap water, contaminated with dangerous microbes.

That evening, after Yom Kippur services, Jordan sat down with the refugees at Tiscornia to break the fast. The next day, the Joint official reported bitterly to New York that although the local Jewish community had tried, this time, “to do the job as they understood it best,” the religious observance had been “most inadequately arranged and created a great deal of dissatisfaction all around.” But whatever the holiday may have failed to deliver in spiritual terms, it shortly appeared that prayers were answered.

Just ten days later, on Friday, October 2, Jordan called the Joint in New York with good news that Cuba’s commissioner of immigration had made a “definite statement” that all the detainees would be released from camp by the end of the month. The Cubans planned first to free the Dutch, with the French to follow, and then all of the others, country by country. Jordan sounded a note of caution, afraid of predictions, yet there was reason enough to celebrate.

At sunset the following evening, most of the camp assembled in front of the building that housed the bodega and above it the prayer room, for which the Joint had provided a Torah. After performing the Saturday ritual of havdalah—marking the formal end of the Sabbath and greeting the secular week as they doused a braided candle in wine—Tiscornia’s Jews burst into a memorably festive observance of the annual holiday of Simchat Torah.

Under the laurels and eucalyptus, men took turns clasping the sacred scroll in their arms and, as tradition required, carried it in

hakafot

or joyful procession around the building—seven times, singing and dancing—past the hedges of crimson hibiscus and the exuberant tangles of bougainvillea. The children too went spinning and jumping, the little ones waving colorful paper flags they had decorated over the previous days and marching with candles. The flames leaped with the children and flickered like fireflies in the deepening dusk, men whirled and stomped and voiced praise to the heavens that stretched above the high royal palms, and Jews at Tiscornia affirmed their faith in a God who had brought them from the cellars of death to rejoice in the hope of a fresh beginning. Even those like Sigmar, Jews of more contemplative faith and natural reserve, not given to dancing, watched and prayed with an added measure of feeling that day, after so many years of terror and chaos.

Camp releases began shortly thereafter. On October 14, 1942, alarmed that they alone might still be confined while the others went free, the eleven German members of B’nai B’rith wrote again to New York, pleading for help. “We are afraid that our cases might not be handled particularly benevolently,” they said, this time in English. But the next day, the Günzburger family was among a group suddenly granted permission to leave. By way of supporting background as to his morals, Sigmar’s files would prove to contain a report sent from Paris six months earlier, in which the French Justice Ministry confirmed that he had no criminal record. By the start of the year, all but thirty-five refugees had won their release, and on February 2, 1943, the last five detainees walked out of the camp in search of new lives.

“This closes the Tiscornia situation for the passengers of the

Guinée

and the

San Thomé

,” Charles Jordan typed his report to the Joint. “

In other words, there is nobody left in Tiscornia

.” The last sentence he added in ink and by hand, almost as if he needed to shape the words with his fingers to feel the reality, the blessing of freedom, he had worked to secure for so many people.

SIXTEEN

LEBEN

IN LIMBO

W

HEN SHE WALKED DOWN

the splendid Paseo del Prado, with its long center island of trees that stretched toward the ocean, Janine felt like a goddess. A goddess of love or of beauty, or, perhaps, given the way the men eyed her hips, a fertility goddess. Habaneros sprang into her path, whipped handkerchiefs out of their pockets, and crouched to wave them just inches above the sidewalk before her, as if they had only been waiting to clean and to polish the granite in advance of her step. “

¡Ay, qué linda!

” they murmured, clicking their tongues. “

Ay, señorita

, to be worthy of such beauty as yours, the street itself must be wearing a shine!”

Months aboard ship and in the open air of the camp all through the hot summer of 1942 had left Janine slim and tanned, and sunlight had gilded the tobacco-hued curls that wound to her shoulders. Her blue eyes were wide as they took in the vibrant scenes of the city, the pastel-colored porticoed buildings; the Paseo’s bronze lions and wrought-iron streetlamps mounted on marble; the chic boutiques selling alligator purses, jewelry, and perfume. Especially, she admired the fashionable strollers, whom she carefully studied in order to learn how to fit into this place, whose cosmopolitan style and colonial charm had so very pleasantly caught her off guard.

“

¿Ay, señorita hermosa, de dónde es usted? ¿A dónde va?

” Oh, pretty young lady, where are you from? Where are you going? “

¡Vamos juntos!

” Let’s go together! Men in short-sleeved tropical guayaberas tossed questions like roses to draw her attention, trailing her steps. But on this particular morning, instead of sternly evading their greetings as she kept walking, she smiled and she laughed.

Clutched in her hand was a bundle of letters she had just retrieved, not only that most precious letter the British surprised her by sending from Kingston exactly as promised, but to her delight, numerous new ones—months’ worth of letters from Roland, all waiting for her in care of the Havana post office. Surely, he must have believed she had gotten them sooner! She imagined his worry over never receiving any reply and headed toward the Malecón, where she could sit on the seawall and enjoy them in peace. If she closed her eyes, the sound and spray and smell of the ocean might let her pretend she was back in Marseille, back in his arms, hearing his tender words in her ear.

Years later, except for the treasured original one, my father would destroy all these letters in a futile attempt to rip their author out of her heart. I can therefore only imagine their fervent expressions of love and desire and how Roland’s pledge of reunion and a lifetime together carried her dreaming over the water and allowed her to hope that nothing had changed. Though the words on the page have been lost, Janine would always remember that she devoured the letters in order, according to date, and that Roland had started the first by quoting their favorite verse from Lamartine:

“

Un seul être vous manque, et tout est dépeuplé

.”

Missing a single person makes your whole world empty

.

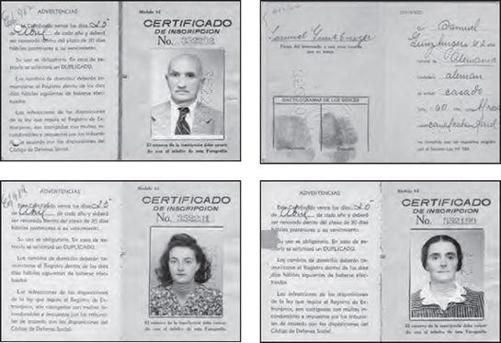

On October 27, 1492, the first few Jews in the New World, presumed to have sailed with Columbus to escape Spain’s Inquisition, spotted the island of Cuba, where they soon landed. Four hundred and fifty years to the day later, another Jewish refugee who crossed the ocean to flee Europe, Sigmar Günzburger, purchased from the Cuban Defense Ministry the requisite foreigner’s registration booklet that came with strict warnings to report any address changes within ten days of moving. For his own life in the New World, he gave his first name as Samuel and dropped the umlaut (ü) from Günzburger. Yet in the black-and-white mug shot pasted into his booklet, No. 352202, he remains European, formally dressed in a suit, white shirt, and striped tie, and his glance is deflected. Gone, the resolute glare of the man in the family portrait taken in Gray. The picture here is one of submission. He gives in to the photo and fingerprinting, allowing his thumbs

—derecho

and

izquierdo

, right and left—to be pressed against a pad of black ink and rolled onto a page like a hustler caught committing a crime. Now as I study the booklet, the eyes in the picture refuse to meet mine, and so I place my thumbs against his, as if some warmth of life might seep through the paper and permit me to feel his hand through the years.

The Cuban Defense Ministry’s foreigner’s registration booklets, including fingerprints, for Samuel Gunzburger, sixty-two years old; Alice Gunzburger, fifty; and Janine, nineteen

.