Crossing the Borders of Time (63 page)

The queen conch

(photo credit 22.1)

But he

was

happy with his feat, and that period was a good one for their marriage. Joining the golf club brought new friends and distracted Dad a little from his ferocious Objectivism. The nature of the club itself, moreover, brought a Las Vegas sort of titillation to their everyday suburban lives. Located just across the river from Manhattan, it was a hangout for celebrities and entertainers who added glitz and glamour, and for well-connected mobsters who brought intrigue and a whiff of danger. Anecdotes about them never failed to make the rounds, and the occasional encounter with a famous or edgy character was fodder for the tables at formal dinner dances requiring closets full of silken evening clothes.

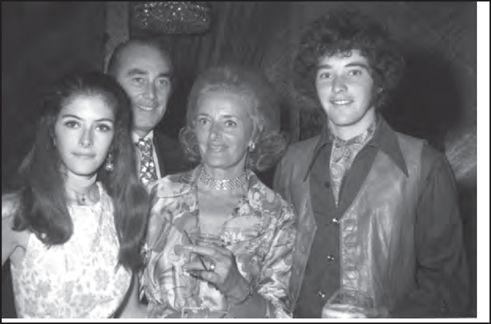

(L to R) Leslie, Len, Janine, and Gary in 1970

With other couples from the club, Mom and Dad now embarked on their first European trip together. They toured the Continent in a whirlwind, staying in the finest places, but Mom also planned a detour to reconnect with relatives. Most important, she and Dad peeled off from the group to stop for lunch in Mulhouse with Edy and Lisette, the first time Mom had seen them since the war. The visit proved awkward, as Mom’s cousin and his wife, listing toward divorce, refused to speak to one another and used their children as intermediaries, even as the family sat together at the dining table. But at a moment when the irrepressible Lisette had my father’s ear, Mom seized the opportunity to draw Edy aside and ask whether there was anything he could tell her about Roland. She didn’t have the luxury to meander subtly to her point. What did Edy know about him? Had he stayed in Lyon when the war was over, or was he back in Mulhouse? Had he ever married? Did Edy know if he had children? Had he gone on to practice law? Perhaps the two had met in Alsatian legal circles?

Edy scowled and cut her short. “

Laisse tomber! N’y pense plus!

” Edy said. Drop it! Forget about him. “The only thing I can tell you is that Roland Arcieri was ruined by women.…”

Janine asked him no more questions. She knew enough about Roland’s appeal for women to understand the message. Being married to Roland, she told herself, might well have proved even more tormenting than her relationship with Len. She would have to try to put aside the fantasies she’d nourished, in the event her husband went wandering again, of seeking out the lover whose memory she had conjured to help her through the awful year of Len’s affair. When they returned home, Mom sadly confided Edy’s words to me. Her dream of someday reuniting with Roland, she said, was one that she had finally buried in Mulhouse, exactly where it started.

On a gray November morning in my senior year in high school, Dad wrote out a range of symptoms on a piece of paper—breathlessness, perspiration, weak pulse, hazy vision—and drove himself into the city to see Charles Friedberg, my mother’s former boss and the chief of cardiology at Mount Sinai Hospital. We learned the news from Dad’s secretary when Mom tried to call him from Newark Airport, as we were about to take off on a tour of colleges that we instantly aborted. Instead, we rushed to the doctor’s office and arrived there just in time to hear the verdict: “Shit, man! You’ve had a heart attack!” Dr. Friedberg exclaimed, studying the electrocardiogram. “I can’t believe you lifted weights this morning! And then you went to work and drove here on your own?”

Dad was only forty-eight; Mom was forty-three, and in that awful moment when we first saw Dad as vulnerable, our lives were changed forever. The very picture of virile health and strength, an athlete and a bodybuilder, a man who never ate or drank to excess, Dad had had a heart attack! We were stunned and terrified by what it would mean for him.

“For Chrissake,” Dad objected, “I maintain my body like a goddamn temple. There’s not a frigging man I know in better shape than I am, but none of them have had a heart attack! Even my own father, who never leaves his sewing table, totally ignores his health, he’s already eighty-six and his heart’s ticking just fine. It’s not fair, damn it!”

Yet Dr. Friedberg said that youthful years of downing quarts of milk at every meal (as Dad had boasted) and eating meat and fats (not to mention his mother’s apple strudel) had done the damage. Cigarettes, excessive stress at work, and a tense, hard-driving, type A personality had all contributed. He ordered Dad home to bed until Mount Sinai called to say a room had opened up for him. He should expect to stay there several weeks in a serious attempt to do absolutely nothing but rest and recuperate and try to calm himself. And until further notice, no more driving, either.

We headed home in silence, the first time I had ever seen my mother in the driver’s seat with Dad reduced to riding as a passenger. So my father’s personality was type A! I had never heard the term before, but felt relieved to learn they had a name for it. Mom was gripping the steering wheel of Dad’s long Cadillac as she headed northward to our exit, driving with scrupulous attention to avoid any sort of error that would invite his criticism. But Dad was lost in inner space. He sat there like a toppled general, bound in shackles and cursing careless strategies that had failed him in his last campaign. All at once, the world appeared immeasurably more dangerous. Dad was our protector: he had sworn he was invincible, and on some level we believed him. I felt weak and hollow, and the future seemed a precipice that dropped off every bit as steeply as the cliffs of the Hudson River Palisades, whose craggy edge we traced along the parkway home.

By the time that Dad was ensconced in the hospital, however, Mom had plotted out a different life for him. As usual, she was wise enough not to broach her goal directly, but rather, as she put it, to slip it through “the back door,” where he could meet it on his own terms. At the time, he was sitting in his hospital bed, squeezing and releasing a coiled metal gripper, designed to work the muscles of the hand and forearm, which he had prevailed on her to smuggle in to him from home.

“Wouldn’t it be crazy if Picasso gave up painting to become a dancer?” she casually put the question to him, forgetting for a moment that Objectivists had scant appreciation for any artist who distorted the noble human form.

“Maybe that would do the world a favor,” Dad snapped. “You know Picasso’s not my bag. What the hell’s your point?”

“Well, then, make it Michelangelo,” she persisted. “My question is the same.” She was crocheting in a chair beside his bed, where she spent the whole of every day from early morning until midnight and then drove home alone, taking care of Dad much as she had nursed Roland twenty-five years before. “It’s tragic if a person doesn’t use the talents he’s born with. You’re a natural salesman, but instead of doing what you’re really good at, you’ve been killing yourself in the factory, and this heart attack is your reward.”

The demands of manufacturing created too much stress for a perfectionist like Len, she thought, while breathing metal dust and poison fumes all day were hazardous as well. She therefore wanted him to sell the factory, and inevitably she persuaded him. Whenever it came to the big decisions in their lives together, Dad trusted her advice completely. He would give up the factory that was his source of pride and, with it, the sacrifices it required and the self-destructive cycle of problems with his workers. But a great deal more reluctantly, he would have to abandon his vision of himself as one of Ayn Rand’s heroes, those defiantly indomitable captains of industry responsible for running the machinery of the world. Mom’s worries for his health, of body and of spirit, required him for the first time to acknowledge his vulnerable humanity. She led him by the hand to a path that saved his life, but it meant he had to walk again in a salesman’s pinching shoes.

Within months of his return to work, Dad sold the factory and moved with his secretary into a two-room office suite in a building just six blocks from home. Once again he became the middleman between the thrumming factory fiefdoms owned and operated by other men of business, more lucky or successful—men whose hearts could take it. Instead of making products, he made sales. He worked the phone and traveled through his region, and year after year won the highest sales awards for the companies he represented, brightly flashing his “phony smile” in pictures of the winners.

Three years later, when Dad gradually became aware of numbness in his fingers, affecting his dexterity and making it difficult for him to button shirts or pick up coins or turn a screw, he seized upon a German word to describe his problem. He had lost

Fingerspitzengefühl

, or “feeling in the fingertips,” he said, finding it less frightening to admit this new infirmity in a foreign language. Besides, how could any weakness that sounded so ridiculous actually be worrisome?

Doctors could not identify the cause and advised him to make the best of it. He fashioned small devices that helped him compensate—a hook that pulled his buttons through their holes, for instance. But before long, his racquet met the tennis ball less reliably than usual, and then even longtime partners like Trudi’s husband, Harry, avoided playing with him, proffering excuses that were hurtfully transparent. On the golf course, when he lost his grip and his driver started flying from his hands as his golf ball left the tee, it was so humiliating that he decided to stop playing, and my parents quit the club. Membership, Mom said, was not worth the cost for her alone, and anyway, it seemed cruel for her to play when he no longer could.

Instead, on summer weekends, though Gary usually begged off, my parents and I headed for the beach for the best times we ever spent together. Occasionally, we’d enjoy long weekends along the coast in Montauk, but often we made day trips to closer-in Long Island. At the beach, in his daring Speedo bathing suit, my father could pretend that nothing much was wrong. Once we were installed upon the sand, disinclined to waste a potentially productive moment, Dad would stage a public show of calisthenics before tackling a crossword puzzle. We’d pass the hours in harmony and always stay until the crowds packed up and the sea regained its dignity. Then, with his white pith helmet clapped upon his head, sitting in a chair like a bwana on safari, Dad would pop the cork on the bottle of white wine he’d chilled all day waiting for our sunset moment. Mom would feed the squealing birds the scraps we’d saved from lunch—always on the lookout for stragglers too timid or hapless to claim their lot—or she’d sit and rake the sand with long red nails to hunt for shells worth taking home.

Sometimes my parents allowed themselves to be lured into the ocean for one late swim. I’d watch them walking toward the water, Mom tucking golden curls into her bathing cap, and Dad with his long-legged, rolling shipboard gait, increasingly unstable, as if the sea were swelling underneath his feet. Hand in hand they’d plunge into the steel-gray waves. The lifeguards would have left by then, and I’d train my eyes to watch for them as they rose and fell beneath the churning Atlantic waters, heading ever farther out. Frantic and exasperated, I’d squint into the distance as I stood at water’s edge, waving my arms and stamping my feet and shouting uselessly into the wind to urge my parents back to shore.