Crossing the Borders of Time (76 page)

In deference to Roland’s marriage, Janine sidestepped all his invitations to return to Montreal. It nonetheless remained her fervent dream that they would meet again someday. Now, in the face of a terrifying medical diagnosis, it became maddening and intolerable to realize that life could end without her ever knowing the consummation of their love. Envisioning the end of life or, at best, the end of her capacity to feel sufficiently alluring to offer him her nakedness—with the expected ravages of surgery and chemotherapy compounding the indignities of age after so many squandered decades—Janine decided to allow herself an unaccustomed act of selfishness. Furious at fate, she refused to die at seventy-one without her dream fulfilled. And although she knew she’d bear the weight of guilt and maybe even punishment for this wrongdoing toward Roland’s wife, she felt that she was owed this singular experience of love. After her surgery, scheduled two weeks hence, the romantic encounter she hoped to engineer could never be repeated.

As Janine pondered how to go about it, she recalled the ruse that she’d devised in 1947 to encourage Len’s proposal by pretending that Aunt Marie’s steamship ticket back to France was really hers. This time, with Roland, she would need to figure out a way to encourage him to visit her. She wanted him entirely to herself, not merely to steal a few hurried hours in the impersonal confines of a hotel room and then be left to spend the night alone. She resolved to keep her diagnosis and impending surgery a secret, wanting neither sympathy nor to cast a pall on a uniquely magical occasion whose memory would be all she had. And so, searching for a plausible explanation to propose a sudden get-together, she hit on the idea of telling him that she wanted to make use of expiring frequent-flier miles. In fairness, she would say then, it was

his

turn to visit her this time. She would suggest that he arrive on the Wednesday afternoon and leave that Friday before her Monday operation, allowing them two days and nights together. It seemed to her the decent thing to make sure he got back home in time to spend the weekend with his wife. Janine felt guilty enough without trying to keep him with her longer.

Roland arrived as handsome and impeccably attired in suit and tie as he had been in Canada. She met him at La Guardia and drove him home, and although she had always imagined sitting closely on the couch in the gentle glow of lamplight in her living room, instead they settled somewhat awkwardly at the kitchen table. She was conscious of the disparity that in Canada she had seen him extracted from his personal environment, yet now her world was spread before him in all its intimate reality. In old allegiance to her husband, she had hidden just one thing—a framed picture taken by

The New York Times

photographer in Freiburg that showed Gary pushing Len in a wheelchair down the Poststrasse with her walking at their side. Len would not have wanted his longtime rival to see him as disabled, so she put that picture facedown in a drawer. But for the first time in her life Janine had her own photographic aspirations, leading her to purchase a disposable camera to document Roland’s visit. She did not expect another opportunity, so at least she would have pictures of his visit to sustain her ever afterward.

She prepared a snack and they talked all afternoon, chiefly of the past and the people they had known. But Roland also told her he had missed her terribly: he was surprised and overjoyed when she finally invited him. He fully understood her unwillingness to return to Montreal for a few clandestine hours together, but it seemed presumptuous for him as a married man to expect her to invite him to her home, so he never dared suggest it. When night fell, they went out to dinner, and afterward they gravitated once again to their separate swivel chairs at the brightly lit kitchen table, where she poured nightcaps, scotch for both of them. She could hardly have settled on a more domestic, less romantic spot in which to entertain him. Still, the hours wore on. Through the glass doors to the terrace, they saw the lights of the neighborhood extinguish all around them, the illumination of Manhattan rosy through the trees and across the Hudson. Yet she hated to bring things to a close, largely because she didn’t know how to handle which bedroom to offer him. Past two thirty in the morning, her inhibitions weakened by emotion, fatigue, and drink, she sketched out three alternatives.

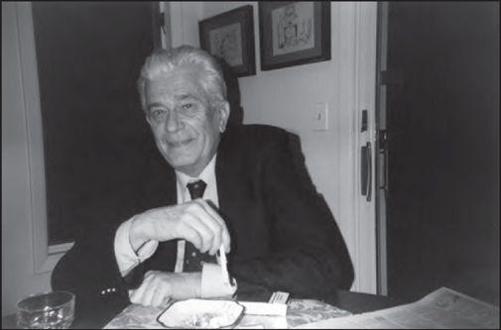

Roland’s visit to Janine’s home prompts her first attempt at photography

.

“You can sleep in the downstairs guest room,” she said, pointing to the room next to the garage, Dad’s former gym, which she had refurnished with twin beds and dressers for visits from Zach and Ariel. “Otherwise,” she added shyly, “upstairs of course there is my room and another guest room across the hall.” He was quiet for a moment and then chose the upstairs guest room, so near to hers and yet so far. Roland mentioned that he always read in bed at night but had neglected to bring a book along, and from a corner bookshelf she unaccountably picked out a history of the Jesuits. It was written by a German Jewish refugee she’d met in Cuba in the war and who contacted me after my article about our European trip appeared in

The Times

in order to reach her and resume their friendship. Recalling that Roland had studied as a youth in a Jesuit lycée, Janine handed him that volume, dense and serious, and after modestly kissing him good night, retreated to her bedroom.

But no sooner was she beneath the blanket, attempting to concentrate on a book herself, than she realized she was wasting her precious opportunity. With just two nights together to make up for all the losses of the past and of the future, she couldn’t bear to spend another minute separated from the man she loved. She climbed out of bed, rummaged in her armoire to find a sheer black nightgown—a gift from Trudi years before, though never worn—and hurriedly changed into it. Then, emboldened by the evening’s scotches and Monday’s scheduled surgery, she crossed the hallway with its antique French clock ticking in the silence and lightly rapped upon his door. She opened it to find him lying on his side, wearing pajamas, intent upon the Jesuits. On the wall facing him, in frames, were her great-grandparents and her grandparents and her parents and Norbert and Trudi and Len and Gary and me and numerous other members of the family. It was what she called in German her

Ahnengalerie

, her gallery of ancestors. Roland was lying on the outside right-hand edge of the queen-sized bed next to the night table.

“As long as you’ve left so much room against the wall, I might as well sleep there,” Janine said, as if moving toward a vacant subway seat. “But don’t worry. I’m not expecting anything but your company.”

Roland lowered the book and gazed in unspoken disbelief at her youthful breasts, her narrow waist, and the promise of her hips and thighs visible through the black transparent veil that flowed around her and reached her ankles. Her feet were bare and her toenails were painted a happy cherry red.

“Come on, move it, buster, I’m climbing in here,” she said lightly, sounding far more confident than she really felt, drawing back the covers and settling beside him. “Okay, now you can continue reading,” she added. “I guarantee I’ll be very quiet here against the wall.” And so she was.

Roland tried to read but soon confessed he could not focus on the pages. “Maybe if you’d given me

Playboy

instead of the Jesuits I might have expected this.” He laughed.

“That’s okay,” she answered. “It’s so late anyway—why don’t you just put the book away, and turn out the light, and we can go to sleep. You know, I didn’t wait so many years not to enjoy the pleasure of resting my head on your chest as I drift off.”

Later on, each would claim it was the other who acted first. But of course I must believe my mother. She reported that he placed an arm across her waist and slid the other behind her neck and slowly started kissing her. Soon there was nothing left between them—not time, or distance, or meddling family, or political upheaval, or duty, or even the fabric of their nightclothes. Aloud, with words and wordless sounds, he marveled at the soft and scented beauty of each part of her. He was generous and worshipful, and she felt tenderly loved as she never had before.

How easy to imagine: it was past the midnight hour of March 13, 1942, and they could hear the halyards clanking, foghorns groaning, hungry cats complaining, and drunken sailors and their women singing on the twisted streets beyond the windows of their hotel room in Marseille. Still they saw each other—young and perfect and trusting but untested—in the moonlight that danced indifferent to the war across the waters of the Mediterranean, filtering through the shutters to paint their bodies silver.

Now they would again too soon be separated, but they had this single moment and, with the greater understanding of life’s vagaries that comes with hard experience, this time they would not squander it. They reveled in each other and kissed each other’s tears away, and then she suddenly leaped up from the bed, pulled him by the hand, and ran completely free and laughing past the swinging golden pendulum of the French clock in the hallway, and drew him to her own bedroom. Hand in hand this time, they escaped the family and crossed the border. There, in her marriage bed with an antique cupid, that most clever archer, perched atop the headboard, at long last Janine held Roland against her pounding heart, and with a vast and soul-deep sigh of coming home, they joined together.

“Whatever happens now, I will have had the two happiest days of all my life,” she called me to confide after he’d returned to Montreal. “And they were thanks to you.”

The following Monday morning I flew to New York and sat in the waiting room of the hospital, my eyes anxiously riveted on the doorway, watching for Mom’s surgeon.

“I was able to preserve her breast,” Dr. Peter Pressman said. “The tumor was very small, and I did a lumpectomy.” A sampling of the lymph nodes in a second operation the following week thankfully showed the cancer had not spread. There would be weeks of daily radiation, the only side effect fatigue but nothing worse. The only sign of surgery would prove to be a delicate line of stitches on her left breast. It seemed to mark the spot where a broken heart had been repaired.

That spring, Gary, Dan, and I met Roland and Mom for lunch in Manhattan at the Symphony Café near Carnegie Hall. He was visiting her again, and to say we were eager to get to know him would be an incalculable understatement. Alone at the bar when I came in, they failed to notice me. Their heads, silver and blond, were bent and touching, and Roland was kissing the palm of Janine’s hand. She looked girlish, her blue eyes full of joy in a way that I had never seen them. I stood there undetected, watching, and it seemed that I was peeking surreptitiously at my daughter on her first date. Roland threw back his head, robustly laughing in response to something that she told him, and he was everything I had imagined: elegant and handsome and obviously in love with Mom. I felt full of gratitude to view this spectacle of myth become reality.

When Gary arrived, he surprised Roland—particularly dignified and formal in demeanor—by clasping him in a jovial embrace. “So you’re the man who was almost my father!” he exclaimed to Mom’s chagrin. “I’ve been hearing about you all my life. It’s amazing to get to meet you!”

For my husband, however, it would turn out to be more difficult to regard Mom’s involvement with a married man as positive, no matter how charming and intelligent he found Roland to be.

“Aside from the issue of

his

marriage,” Dan objected, not unreasonably, “this will keep her from exploring other relationships with men who are available. I’d hoped someday she might remarry.”

“There could be no other man for her,” I countered, and Gary agreed with me.

“Honestly, there never has been,” my brother added. “He’s the only man she’s ever fully loved. No one else would interest her. To whatever degree that she can be with him, he’s the only one she’s ever wanted.”

After lunch that day, I accompanied Mom and Roland as they walked along Fifth Avenue arm in arm, very slowly, a royal couple in procession, glowing. Their feet barely moved along the pavement, and as I found myself outpacing them, I stopped to turn and wait, replete with something that resembled the contentment of creation. I would not have been surprised to see New Yorkers, however jaded, line the street to cheer in honor of a love reborn, now transcending every obstacle.

During Roland’s next trip to New Jersey six weeks later, the happy couple invited me to spend some time with them. Dan was back in Maryland with our children, and I was at my mother’s house, staying in the upstairs guest room. Over dinner at a local restaurant—the scene of many memorable meals I’d shared with both my parents—Roland indulged me by recounting the story of his life and origins, beginning with his grandfather, the shoemaker from Genoa. It was fascinating to come to know the man who had always been a mystery, a picture in my mother’s wallet.

“I feel robbed,” Mom told me later, when we got home. “It’s sometimes hard to keep in mind how lucky I am to have him back, when I consider how very much time I missed.”