Crossing the Borders of Time (79 page)

My brother, Gary, certainly lived the story with me from the start. He not only offered his perceptive insights and judicious guidance, but also rode to the rescue each time I called. To our grandparents, Sigmar and Alice, I am boundlessly grateful. The little, scuffed brown leather valise or

Köfferle

in which they clung to a trove of official documents, identity cards, visas, letters, telegrams, and photographs made it possible to follow their fates under Hitler’s regime and to trace our family roots through the centuries. With the owners gone, it was hard to fathom the resilient endurance of the vibrant, pulsing artifacts of lost days that imparted a world of information to me.

The discerning counsel of my cousin Richard Herzog was an incalculable gift, and with his wife, Barbara, he provided painstaking dissection of every issue on which I sought his opinion. Other cherished relations here and in France proved notably helpful, as well. Among them, I thank Hanna “Hannchen” Hamburger; Isabelle, Janine, and Huguette Cahen; François Blum; Lynne Marvin; Lynn Ullman; Suzanne Steinberg; and Carol Weil. My Parisian cousins on my father’s side, Danielle Fakhr and Hélène Putermilch, prepared me to tackle this book years ago when they taught me to speak French and introduced me to their beautiful country.

Of course reporting in France was no hardship assignment. The story took me to Mulhouse, Paris, Gray, Langres, Lyon, and Marseille, and in each city I found gracious and ready assistance. In Mulhouse, where I owe so much to Roland’s sister, Emilienne, I am also obliged to Benoit Bruant and Geneviève Maurer. In Marseille I thank Guy Durand of the Direction du Patrimoine Culturel. In Lyon, I am thankful to Marc-Henri Arfeux, who welcomed me—a stranger who showed up unannounced at his remarkable door—with genuine interest and warmth. A writer himself, he greatly furthered my knowledge regarding my cousins who had lived in his building and, in an instant, arranged for me to meet with his mother, Monique Arfeux, and his upstairs neighbor, Pierre Balland, who had both personally known the Goldschmidts and related still-haunting memories of them.

Also in Lyon, I thank the Centre d’Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation and Roselyne Pellecchia. Through the Centre de documentation juive contemporaine of the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris, she located the chilling documents that detailed what happened to Mimi Goldschmidt and her three children, as well as to Roger Dreyfus and Bella Picard, among twelve hundred Jews deported on Convoy 62 from Drancy to Auschwitz.

Yannick Klein, former Directeur Général des Services Municipaux of the city of Gray, performed an immense service in connecting me with André Fick—my mother’s friend and one of Mayor Fimbel’s key aides during the occupation of Gray. André Fick’s eyewitness account of that period,

Gray à l’Heure Allemande: 1940–44

, provided vital historical detail for my chapters describing the fears and compromises imposed by that time, as well as its moments of quiet heroism. In Gray, as well, I thank Rémi Hamelin for the background and tour he provided.

In Germany, Walter Preker extended constant assistance and lasting friendship. His expertise is well demonstrated by the fact that when we first met in 1989, he was the mayor of Freiburg’s press secretary, a post he continues to hold to this day, even as city hall has changed hands. On each of my trips there, Walter facilitated my reporting in Freiburg and Ihringen, and when I returned home, he followed up my every request for added information or pictures. A real favor—he even politely corrected my German! It was on my first visit that Walter set up an interview with Mayor Dr. Rolf Böhme, whose initiative to invite Jewish former citizens to return to their homeland actually served to launch my endeavors.

Through Walter, I met with Professor Hugo Ott, the renowned Heidegger scholar, who shared his research into the 1940 deportation of all Freiburg’s Jews and the suicide that day of Therese Loewy. I am equally indebted to Dr. Hans Schadek, the former chief archivist of Freiburg and an authority on its Jewish history, and to his successor, Dr. Ulrich Ecker, who both devoted much time to discussing the painful history of Jews in the region under the Nazis and back through the centuries. From the archives, they and Dr. Hans-Peter Widmann unearthed important pictures and documents for me.

Among others in Freiburg who aided my research, I note with appreciation Sissi Walther and Michael and Rosemarie Stock. In addition to his other kindnesses, in 2005 Michael permitted the artist Gunter Demnig to imbed so-called

Stolpersteine

—“stumbling stones,” or blocks engraved with my grandparents’ names—in the sidewalk in front of Poststrasse 6, as part of a project that has already memorialized more than 30,000 victims of Nazism throughout Europe. The

Stolpersteine

on the Poststrasse literally paved the way for a first family reunion, because an unknown French cousin, François Blum, happened to notice them on a trip to the city and began a quest to find Sigmar’s descendants. In the dispersal of the Nazi years, branches of the family had become disconnected, but François figured out that our great-grandfathers were brothers, and I was thrilled to be found.

When it came to researching my mother’s escape from France, the archives of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in New York proved invaluable. One has only to read the wartime documents in the relief agency’s files to feel the desperate urgency of its efforts to save lives. I came away inspired by profound respect and gratitude for its mission and staff.

My account of the voyage of the

San Thomé

owes a great deal to Dr. Margalit Bejarano, former academic director of the Oral History Division of the Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She generously allowed me to use the transcripts of two oral histories she conducted in 1987 with passengers Lotte Burg and Emma Kahn, who had escaped to Cuba on the same voyage as the Günzburger family.

Dr. Michael Berenbaum, former director of the United States Holocaust Research Institute at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, arranged with Sarah Ogilvie and Scott Miller of the museum to put me in contact with numerous former refugees who had been interned at Tiscornia. I was surprised to learn that the long-term detention of Jewish refugees there had never before been closely examined and, moreover, that no one could tell me where the one-time camp might have been situated. Not former refugees who had spent six hard months there, nor American or Cuban officials, nor scholars, nor anyone I consulted in several agencies that regularly deal with worldwide Jewish issues. The camp’s location appeared on no map, and guidebooks and histories shed no light on the matter. That I finally managed to stand outside its gates I owe to a marvelous Cuban woman whom I cannot name for fear of causing trouble for her. She led my mother and me to the barred compound—transformed into the Instituto Superior de Medicina Militar—where heavily armed military guards ordered us not to approach or take any pictures.

Maritza Corrales, an expert on Cuban Jewry, proved a remarkable guide in Havana. She took us to the places that Mother remembered and brought us to meet another alumna of St. George’s School who, after sharing recollections and yearbooks with us, succumbed to tears as she and Mom ventured to sing the old St. George’s anthem together.

In regard to Moisés Simons, musicology professor Robin D. Moore, now of the University of Texas at Austin, steered me to fascinating research that traced the Cuban-born composer’s mysterious lineage to Jewish immigrants from the Basque region of Spain. According to Dr. Moore, the musician—while living in Paris before World War II—quite likely changed his name from Simón to Simons to disguise the fact that his background was Jewish.

In Washington, Norman Chase of the periodicals collection at the Library of Congress helped obtain French and English newspapers from the late 1930s and early 1940s that sketched a first view of history. I was grateful, as well, to my esteemed

New York Times

colleague, William Safire, who entrusted me with large stacks of personal copies of

The Times

he had lovingly saved through the war and ever thereafter. Though their brittle pages risked damage from handling, he unstintingly urged me to use them, as was his way. For broader and deeper analyses of the period, I commend with gratitude and respect the dedicated scholars and historians whose works provided a firm and essential foundation for all that I wrote. I list many of their superb studies in the bibliography at the end of this volume.

I have been truly lucky over the years to be bolstered by dear friends who remained interested and kept faith for so long. Susan Goldart has been my treasured ally from the very first day—a trusted confidante, caring advisor, and nuanced reader. I have prized the heartfelt camaraderie of Naomi Harris Rosenblatt, who, as a writer, shared my adventure and lent her perspective, both as a biblical scholar and, like Susan, a psychotherapist with valuable insight on family dynamics. Barbara Wolfson and Harvard English professor Elisa New each read early drafts of the manuscript and provided astute observations. Anne-Marie Daris was a valued consultant on all things French: she checked my language, brought me Lamartine verses, and invited me to the mountains of France, where Roland had served with the Chantiers de la Jeunesse. Jean B. Weiner, our lifelong family friend, openly shared her memories with me. Kendra and Mark Sagoff, Miriam and William Galston, Margery Doppelt, Larry Rothman, and Rangeley Wallace comprised a responsive council of intelligent voices on intricate questions.

I am thankful to Rabbi M. Bruce Lustig, our clergy, and all our wonderful friends at the Washington Hebrew Congregation, too many to name, who formed a circle of care that felt like a family and enabled two transplanted New Yorkers to feel at home in the nation’s capital.

Our incisive daughter, Ariel, read the whole book aloud and gave me important feedback. I was grateful to have her zesty prodding at moments when my energy faltered. She and her brother, Zachary, grew up with this book as a selfish sibling, and I am sure they are thrilled to see it kicked out of the nest. To my son, I extend a special measure of thanks for, second only to me, Zach lived with this book on his desktop. I am profoundly indebted to him for the countless late hours he spent reading and editing, reacting with eager delight to the task of weighing a problem of phrasing, regardless of every other demand on his time. Like Ariel, he brought to the manuscript a sharp eye, keen ear, and sensitive grasp of the story.

Finally, this book could not have been written without the vast and forbearing support of my husband, Dan Werner. He has endured its many fitful demands for time, attention, and travel. His only complaint throughout came on a visit to Gray, when he grumbled that the next time his mother-in-law felt compelled to escape, he hoped she might pick a more lively refuge. A journalistic advisor, technological savior, moral compass, and devoted partner, he has been unfailingly helpful and thoughtful in ways that would take a book to describe.

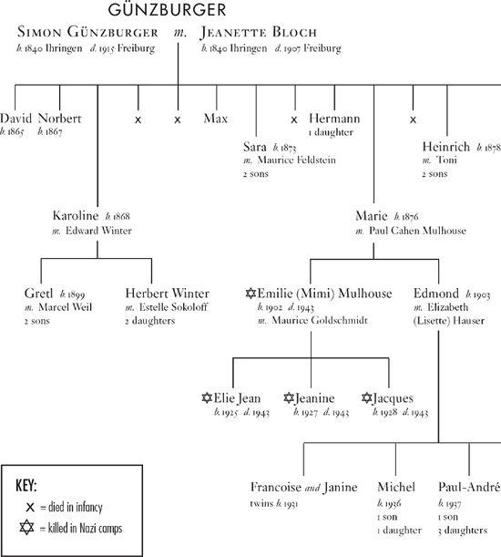

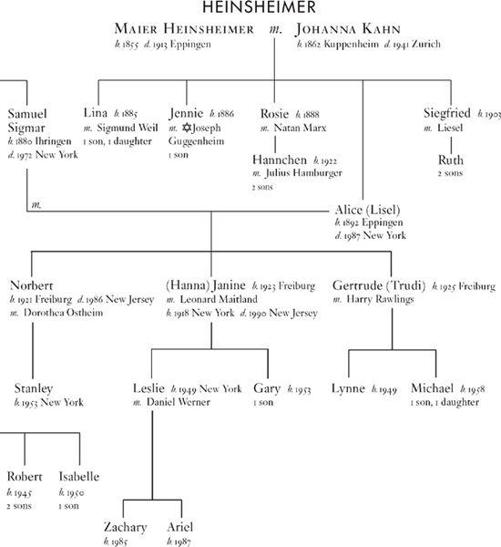

FAMILY TREE

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY