Crossing the Borders of Time (37 page)

The destination the

Lipari

withheld from the public: Casablanca. There the refugees would transfer to a Portuguese freighter from Lisbon, chartered to take them across the Atlantic. The trip would prove longer and sail closer to the brink of disaster than any who embarked that day could have imagined. But for each, this escape was miraculous, the result of arduous negotiations and detailed arrangements handled on a case-by-case basis by rescue organizations working through Lisbon, Marseille, and New York. Indeed, the full extent of their good fortune was yet to be known, for these passengers would be among the very last Jews to slip out of France. Thousands of other desperate refugees who made their way toward Marseille seeking escape would soon find themselves trapped. In the region of lavender fields and sunlit towns whose names conjure dreams of art or vacation—Arles, Aix-en-Provence, Saint Rémy, and Cassis—they waited, hungry and fearful, in makeshift camps that were French holding bins for transports to Nazi death camps in Poland.

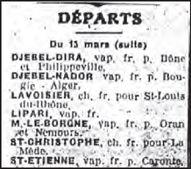

Marseille’s commercial newspaper

, Le Sémaphore,

listed seven vessels sailing from port on March 13, 1942, but the destination of one, the

Lipari,

was not revealed

.

(photo credit 14.1)

The steamship

Lipari,

commissioned in 1922 out of Le Havre

(photo credit 14.2)

On March 27, just two weeks after the

Lipari

sailed, the first French deportation took 1,112 Jews on a three-day journey to Auschwitz from the camp of Drancy in the suburbs of Paris. The Nazi leadership had adopted a “Final Solution of the Jewish question,” defined as “the complete annihilation of the Jews,” at the Wannsee Conference the previous January. It called for exterminating what they estimated as eleven million Jews in Europe, including those in undefeated or neutral countries. Now, to achieve Hitler’s goal, the Germans demanded French help in arresting, interning, and deporting Jews from all parts of the country.

In response to Berlin, the French decided first to offer up stateless Jews found south of the line along with foreign or stateless Jews still in the northern Occupied Zone. The quota of Jewish bodies to be supplied to the Germans had to be filled, and under a

loi du nombre

, a law of numbers, any life spared meant the inexorable sacrifice of somebody else. On June 27, the Germans ordered fifty thousand Jews to be supplied from the Unoccupied Zone. Under terms of the armistice that required France to turn over any former Reich citizen upon demand, the Vichy government—with Prime Minister Pierre Laval now in effective control—absolved itself of any obligation to provide foreign-born Jews with asylum. But three days later, Adolf Eichmann, head of the central German security office branch for Jewish affairs, more fully revealed the scope of the Nazis’ Final Solution when he personally carried new orders to Paris:

all

Jews in France, foreign

and

native, would henceforth be targeted for deportation. Citizenship no longer offered protection to Jews.

The impact on French emigration proved drastic. Already in February, a month before the

Lipari

sailed, the Germans widely reissued their previous ruling that forbade the emigration of Jews from the Occupied Zone without prior approval from Himmler. (As chief of the dreaded SS, Himmler was responsible for implementation of the Final Solution.) In the Unoccupied Zone, Vichy’s aim of deporting foreign Jews first, before French citizens—“

pour commencer

,” to begin, as Laval would express it—swiftly led to a similar crackdown. On July 20, Vichy’s Interior Ministry suspended exit visas previously issued to all foreign Jews except those from Belgium, The Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Quickly thereafter, on August 5, Vichy’s aim of deporting foreign Jews first produced a stringent order to regional prefects. With few exceptions, the order directed that

all

foreign Jews who had arrived in France after January 1, 1936, be promptly sent to the Occupied Zone and that any exit visas they held be summarily canceled. The following month, Laval explained the directive by saying, “It would be a violation of the armistice to allow Jews to go abroad for fear that they should take up arms against the Germans.”

As a result, more than two-thirds of the 75,721 Jews deported from France would ultimately prove to be foreign born, despite the fact that they accounted for only half the Jews then in the country. Few of those seized would survive the ordeal to the end of the war. Three-quarters of the deported were arrested

not

by the Germans but by French policemen, while besides the deported, another four thousand died or were killed while still in French camps. More than half the dead—almost forty-two thousand, mostly foreign—were deported from France in that same year, 1942, that Janine and her family escaped from Marseille at the very last conceivable moment.

That July, a notorious operation involving nine thousand French police produced the arrests of nearly thirteen thousand Jews around Paris. The so-called Vel d’Hiver roundup was named for the sports stadium where those arrested, including more than four thousand children, were held for five punishing days with meager amounts of water and food before being deported to face execution. The following month, the pace of arrests sharply picked up in the southern department of the Bouches-du-Rhône, where many deported already held emigration visas in hand. On August 11, a convoy from the camp of Les Milles near Aix-en-Provence took adult German and Austrian Jews with last names that began with the letters

A

through

H

. Thousands from other French camps were forced onto trains in the following days, while French-run dragnets on August 26 and 27 snatched 6,584 more Jews from throughout the Unoccupied Zone for convoys headed to death in Poland.

Even evading capture in France, the Günzburger family’s flight to freedom would have been blocked in Morocco had they left any later. That summer, shortly after they sailed from Marseille to Morocco and from there on to Cuba, Joseph J. Schwartz, the Joint’s charismatic European director, cabled the rescue agency’s New York office from Marseille to report:

NEW DIFFICULTIES HAVE ARISEN WITH REGARD MOROCCAN EXIT VISAS EVEN FOR THOSE WHO ALREADY HAVE FRENCH EXIT VISAS THUS MAKING IT DOUBTFUL WHETHER ANYBODY WILL BE ABLE DEPART CASABLANCA

.

As obstacles mounted, Schwartz rushed for help to the American chargé d’affaires in Vichy, S. Pinkney Tuck, who said he had already objected to Laval and other French leaders, and there was nothing more he could do. Schwartz reported Tuck’s resigned observations back to the Joint in New York: “Washington is fully informed of every detail and the French Government knows our reaction to the inhuman steps which they are taking,” Tuck had told him. “I do not believe that anything can be done by anybody for the time being. The only language these people understand is force.”

Quickly the situation grew worse.

PRACTICALLY IMPOSSIBLE EVEN JEWS FRENCH NATIONALITY OBTAIN EXIT VISA

, Schwartz wired New York on September 11, and the trend he noted was soon formalized. On November 8, the Vichy government called a total halt to granting exit visas, as the Allies launched Operation Torch, attacking the Moroccan and Algerian coasts. The landings—which Churchill optimistically hailed as “the beginning of the end” of the war—met French resistance in Casablanca, and Pétain broke off diplomatic relations with the United States. American fighters and warships engaged with French fighters protecting French warships, submarines, and transports, and as fire swept through the harbor of Casablanca, the

Lipari

, on which the Günzburgers had escaped just the previous March, was destroyed.

Three days later, on November 11, under Hitler’s orders, the

Wehrmacht

stormed over the Demarcation Line and swept south to the sea. Operation Anton, the Nazi code name for the seizing of France, met no armed French opposition, despite its clear violation of the 1940 armistice between the two nations. Unchecked by Vichy, the Germans easily grabbed the rest of the country and conclusively sealed the routes of escape for all Jews still caught inside France—the foreign, the stateless, and the French citizens—leaving them equally subject to being deported. Within a month of taking Marseille, Hitler ordered the immediate deportation of every Jew still to be found south of the line.

By January 1943, the Germans unleashed Operation Tiger, a massive roundup throughout Marseille that included—besides Jews—Communists, petty criminals, and others condemned as undesirables. It was the first step in a Nazi plan to demolish the historic port district in order to root out resisters already traced to anti-German guerrilla actions and to control the area in advance of a possible Allied attack from the sea. When they finally came, on May 27, 1944, American bombing raids on Marseille killed more than two thousand, mostly civilians, and also leveled much of the city where Janine and Roland had shared their last night.

This, then, was the menacing world that Janine escaped when she was forced to board the

Lipari

for Casablanca, leaving Roland behind. That she loved him so much, while understanding so little of the dangers involved in remaining in France, would color her future and cloud her memories of that fateful day. Instead of embracing the last-minute chance to survive, at the age of eighteen, surrounded by madness and evil for almost a decade, she viewed leaving as exile, because the only place she felt safe in the world was within Roland’s arms.

Janine stood fixed at the

Lipari

’s railing as the last sea-tossed golden mimosa drifted away, the last curious gull wheeled back to shore, and Roland—capable of rowing no farther—finally turned his boat toward the pier. Twisting his treasured ring on her finger, she tried to find solace in its solid reality there on her hand, as if it might guarantee they would be reunited. With everything that mattered to her rapidly shrinking into the distance, she felt enraged. Yet she was not the passenger who cursed aloud. Rather, the male voice that startled her out of her own dark reflections expressed a view she could not bear to hear.

“

Merde à la France!

” She spun in surprise to see several bearded Orthodox Jews, diamond dealers from Antwerp, standing beside her. The speaker’s native Polish accent saturated his acquired Belgian French, as once again he swore, “

Merde à la France!

” Shit on France! He was wearing a long black coat and broad black hat that he clutched to his head to keep it from blowing away, as he reached over the side and spat in the sea. “The cowardly French are no better than Germans, only less honest,” he contemptuously remarked to his fellows, who took his words as a cue to follow suit and spit in the waves.

Janine studied the man—his grim, black attire, his bony frame and narrow hunched shoulders, his skeletal fingers hooked over the railing—and meanly observed that he looked like a crow. His attack on France, with Roland by now just a dot on the water, clawed at her heart. In him she saw the embodiment of all her problems: he was one of those Jews who attracted suspicion wherever they went and incited hatred from the rest of mankind. Why should her existence be shaped and confined by people like this, who scoffed at the need for winning acceptance, when all joy in her life had solely depended upon remaining in France, yes

belonging

in France like anyone else?