Crossing the Borders of Time (34 page)

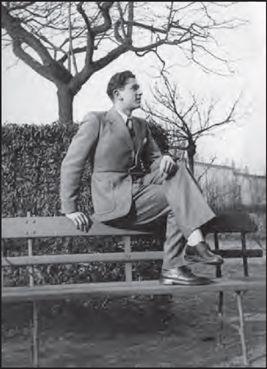

Roland after his return to Lyon from recuperating in Ecully

He relented the following evening, but only because an oil painting in a thick gilded frame, hanging directly over her bed, slipped from its nail. The noise brought him running to find that her head had crashed through the canvas, ripping a crater into the landscape. Still, he refused to meet Roland and forbade Janine to become involved with a non-Jewish man. It would only lead to heartbreak for he would never permit her to marry out of the faith, Sigmar warned. In any event, he added, she knew very well they soon would be leaving so that separation was inevitable.

Unexpectedly, that last rationale helped to make her mother an ally. “Ach, puppy love,” Alice pronounced with a tolerant sigh. She agreed to meet Roland during one of her husband’s trips to Marseille, and impressed by his charming manners and respectful demeanor, she could not see the harm in allowing the pair to spend time together. In view of Sigmar’s plans to emigrate, the relationship, for better or worse, would necessarily end. Alice would not dare to challenge Sigmar about it, but she agreed to a mode of silent acceptance, as long as Janine was careful not to invite her father’s suspicion by coming home late or making a public display of herself.

Janine was not permitted out in the evenings except for very special occasions when Alice helped to cover her absence because Roland had splurged on seats at the Opéra or tickets to hear a favorite performer. The couple grew misty together, holding hands through

La Traviata

, and sat transfixed before Charles Trenet, the jazzy, blue-eyed

Fou Chantant

or Jester of Song, who attained wild acclaim through the widespread demand for something uplifting. For the most part, however, Janine and Roland found their time with each other restricted to weekends and late afternoons, when they sometimes went to the movies on the rue de la République, always eager to catch a new film with Tino Rossi, the ebony-haired Corsican heartthrob who had popularized the song “J’attendrai” that they now adopted as theirs. Far more often, they walked and talked, followed their interests through secondhand bookstores, and watched daylight dwindle in their preferred cafés—le Royale or le Tonneau—contentedly sipping cups of Bovril. They were “dancing on the edge of a volcano,” as Roland put it to her, enjoying the moment, blinding themselves to the inevitable.

As they strolled through town, they paid little attention to threats against Jews—

TO KILL A JEW IS TO AVENGE A SOLDIER

—scrawled in chalk on buildings and walls. Rather, they tried to find places to relax their guard about being noticed by someone who might report them to Sigmar. Roland took her exploring the city’s concatenation of hundreds of obscure, covered passageways known as

traboules

, which permitted the cognoscenti of Lyon to weave through buildings from street to street without being seen. These internal alleys were originally designed to enable silk workers to shield the delicate fabrics they carried from dirt and bad weather, and later would help hunted members of the Resistance elude the Gestapo. In hidden, decoratively sculpted interior courtyards between the

traboules

, standing against slim Renaissance pillars or under groined vaults of stone gothic arches, Janine and Roland found shadowy corners for sharing their love in the only privacy available to them.

In the movie theater they hid in the dark in the last row and snuggled together under the coat that Roland brought along regardless of weather. Their hands and fingers went on adventures, sneaking past buttons and sliding through zippers, cautiously edging down uncharted ridges of muscle and bone, and into the warm, hidden places where once again they found one another. Wordlessly, they dissolved in kisses and imagined a future more glorious than any film on the screen. Though consumed with desire, they lacked a place to succumb to temptation, even had they both been prepared to reject the prevailing sanctions against premarital sex.

One afternoon, they ventured into the Boîte à Musique in the passage de l’Argue, a covered arcade between the place de la République and the place des Jacobins. Above the long, narrow bar, the second-floor hallway was lined with a half dozen doors that each opened into a small cubicle where a faded sofa, a lamp, and a table provided a décor dictated by function: couples with no other space to spend time alone rented the closetlike rooms by the hour. When they entered the boîte, Janine was too embarrassed to climb the stairs with Roland, so he went up first, and she followed five minutes later. Upstairs, they were amused to discover that the door of each room had a small opening cut into the center, covered by a sliding wood panel, which permitted the waiter to pass drinks discreetly to the patrons inside. When the waiter knocked to alert them to open the service window, both Janine and Roland rushed to the door to peer into the hallway. At that moment, the panel slid open in the door facing theirs, and they found themselves staring directly into the face of the patron in the opposite room, who apparently thought the knock was for him.

In one paralyzed moment of disorientation, Norbert and Janine stared at each other across the narrow breach of the hallway. Neither brother nor sister could muster speech under the mortifying circumstance that called upon them to acknowledge each other. Norbert’s glance darted back and forth between Roland and his sister, an older brother’s possessive sense of honor and outrage ablaze in his eyes despite his having been caught in the exact same position of compromised virtue. With Norbert still gawking in disbelief, Roland slid their panel back into place, and as soon as they judged the coast to be clear, they relinquished all plans for sexual intimacy and hurried back to the violet twilight of the place Rambaud, for fear Norbert would reach the parents before her. By getting home first and holding her tongue, she was able to strike a pact of secrecy and see it prevail.

“What in hell were

you

doing in a place like that?” Norbert hissed to her later. To which she replied, unusually brazen, “I guess I was doing the same thing as you.”

“But it’s not the same!” Norbert countered.

“Oh, no?” she successfully bluffed. “Why don’t we ask for Father’s opinion?”

Late that fall, anti-Jewish measures grew increasingly harsh, with the staggering fine of one billion francs imposed upon the Jews of France for their purported involvement in the killing or wounding of German officers in the Occupied Zone. Bombs felled synagogues in Paris, and the Germans arrested and interned one thousand prominent French Jewish professionals around the capital. On October 23, under orders of

Reichsführer

Heinrich Himmler, head of the Gestapo and the

Waffen-SS

, Jews were forbidden to emigrate from Germany or any area of Reich occupation. At the end of the year, the threat level soaring, Vichy announced that

all foreign Jews

who had arrived in France since January 1, 1936, would be rounded up and consigned to forced labor battalions or internment camps. If the Pearl Harbor invasion on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. declaration of war raised any spirits in France, Roosevelt’s prior refusal to enter the conflict in Europe, along with America’s closed-door policy toward refugees, gave Jews little hope that Uncle Sam would come to their rescue anytime soon.

Less than two months later, in late January, when the rule went out to regional prefects to pursue the internment of all foreign Jews, Janine was seized by terror when, heading off to work one morning, she saw French police loading Jews on a truck. Fearing her parents had been arrested, she ran back home and raced up five flights of stairs to their silent apartment. She rang the bell, but nobody answered. Over and over, yet no one responded. Breathless and sobbing, she pummeled the door with her fists and cried for her mother, and then she collapsed against the wall in the hall, too drained to move until she heard a noise at the door and Alice poked out, still dressed in her nightgown with braids askew.

“

O mein Gott!

” Alice exclaimed, as she dropped to the floor at Janine’s side. “What’s wrong? Are you hurt? Are you sick? Why aren’t you at work?”

“I thought you were taken!” Janine wailed. “Why didn’t you answer the door? I was ringing and banging! On the street … I saw them forcing Jews on a truck! I was sure they got you and Father!”

But Alice and Sigmar had simply stayed in bed, the only place to hide from the cold in their unheated apartment. From that moment on, Janine would board the bus to work every morning wearing the new double-breasted, fur-trimmed brown suit and matching brown coat that her parents had bought her in optimistic anticipation of leaving the country. To ensure their daughters would travel in style, they had taken another loan from Maurice and pooled their accumulated textile rations to have outfits made for the girls. That both chose dark fur-trimmed suits to descend well dressed in the unaccustomed heat of Havana proved how little they knew about its climate, as well as how quickly they hoped to move on to New York. With the fresh understanding that any Jew in France faced instant arrest at any time, Janine grimly determined to wear these fashionable new clothes to work every day so that wherever she landed, she would look like a lady when she arrived.

Over the previous months, Sigmar had been quietly pursuing escape with newly desperate, fear-stoked obsession. It was only good fortune that having blindly waited in Europe for far too long, he finally sought the permits they needed a half step ahead of the effective enforcement of new regulations. His goal was to get all requisite permits approved in time to qualify for a sailing planned for mid-March. Tentatively, HICEM had their places reserved on the

Lipari

, a ship leaving from Marseille for North Africa; from there, another vessel chartered by the Joint out of Lisbon would take them to Cuba.

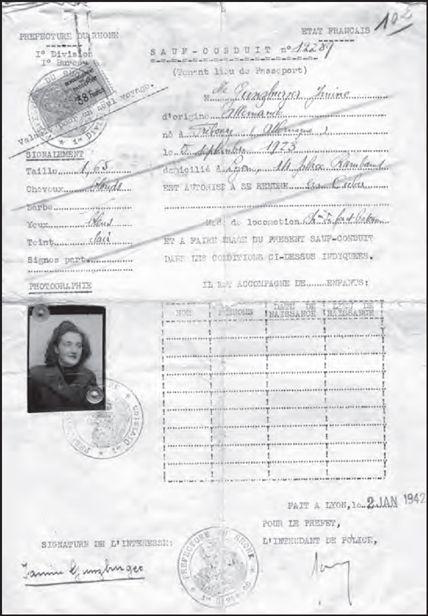

In late December he had gone to a Lyon notary’s office with two Jewish friends—one from Freiburg, the other from Mulhouse. Both had to attest that they knew who he was and where he was from, in order to help him obtain a document to take the place of a birth certificate, which he could not hope to acquire from Germany. A week later, because being “stateless” they lacked valid passports, he had brought the family before police officials at the Préfecture du Rhône to apply for temporary safe-conduct passes permitting them to travel by train to Marseille and from there to leave France. On January 3, he had gained exit visas that would expire in three months; two days later, the Cuban consulate had granted them permits to land on the island as “tourists”; in late February, they obtained stamps of approval to pass through Morocco; and on Saturday evening, March 7, 1942, a cable from one of the rescue agencies arrived on their doorstep bearing the news that they were cleared for departure the following Friday. They were told to report to Marseille a day before sailing to obtain further visas from the Préfecture des Bouches-du-Rhône permitting their boarding the

Lipari

.

Although Herbert would eventually sponsor more than one hundred refugees for entry into the United States, he could not persuade the Goldschmidts, Marie, or Bella to let him arrange passage and visas for them. Maurice and Mimi were stubbornly fixed on remaining in Lyon, both insisting the persecution that targeted foreign-born Jews would not really apply to those who were native-born French. Besides, Maurice confessed, he was afraid of the water, had not learned to swim, and therefore could not bring himself to travel by ship. Marie and Bella, of course, would not think of leaving without the rest of Marie’s family. On March 8, Maurice loaned Sigmar $500 for traveling money, a sum that Sigmar duly recorded, along with his own reminder to calculate interest, in the notebook where he scrupulously listed the many debts he had been forced to incur since fleeing Freiburg.