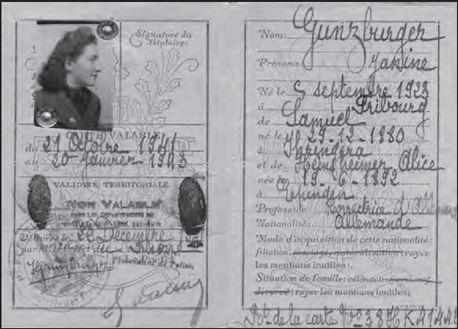

Crossing the Borders of Time (32 page)

Janine’s identity card in Lyon describes her profession as a corrector of German

.

Unable to recapture what she’d shared with Roland in her final weeks in Mulhouse, she became a satellite in his entourage. She was thankful for any time in his orbit yet endured in a state of besotted frustration. After work, she joined groups of young people who sat in cafés on the place des Terreaux behind city hall, where Bartholdi’s fountain—a chariot drawn through the waves by four straining horses—appealed to their zest to forget the war and get on with life. But Roland was so taken with his card games and the companionship of fellow students, regardless how little he actually studied, that he barely seemed to notice her there, hungering for any sign of affection that would validate her devotion to him. To have found Roland, only to have him still out of reach, was a shattering disappointment. The fantasy that had nourished her spirit, soothing the nightmares of persecution, had fed rapturous dreams of impassioned reunion. Now she berated herself for her foolishness in having magnified her importance to him.

While her days were shaped by longing to see him, their meetings—mostly by way of her persistently searching, knowing he would be strolling the rue de la République or cavorting with friends in habitual haunts—generally proved deflating and painful. Desperate to win his attention and then his heart, she combed through her days for interesting nuggets to share. Roland had only to bring up a book he had read to send her dashing off to a bookstore, where, lacking the means to buy it, she would devour as much as she could without provoking a salesclerk’s displeasure, just to learn enough to discuss it with him.

That March 1941, news of the death of Alice’s mother, Johanna, arrived from Zurich, where she had lived in despair with her daughter Lina since fleeing Eppingen. (Alice rushed to Zurich for the funeral, but by the following year, neutral Switzerland would close its borders to Jews and even turn refugees back to the hands of the Nazis.) In the same month, German officials informed Berlin that the French government had interned forty-five thousand foreign Jews in camps in the Unoccupied Zone, as permitted under the law enacted by Vichy the previous October. “The French Jews are to follow later,” their report asserted of the Vichy internments, which by then outnumbered those that the Germans enforced in the Occupied Zone. By June, sweeping new legislation expanded the Vichy government’s right to intern

any

Jew, foreign

or

native, for

any

reason, including suspicion of being a Jew. A revised

Statut des juifs

further excluded Jews from jobs and professions and mandated a scrupulous new census, requiring them to register in person with details of their residence, family background, and financial assets. Two weeks later, the General Consistory, the chief administrative body representing French Jews, voted in favor of cooperation befitting a loyal citizenry.

In July, further legislation empowered Vichy to seize Jewish property through an aggressive program of Aryanization already in place in the Occupied Zone. Citing the goal of erasing “all Jewish influence from the national economy,” it provided for the confiscation of any Jewish-owned property. Authorities arrested the poorest Jews first under the pretense that internment, however miserable, reflected humanitarian motives. The betrayal long dreaded by France’s native-born Jews—that they would be lumped with disenfranchised Jews who, being new to the country, could not expect its equal protection—sharply became reality now.

In the face of these alarming new rulings, Sigmar embarked on the first of many trips to Jewish aid agencies in Marseille seeking papers and passage out of the country. Week after week, Trudi accompanying him to help with translation, he traveled by train and then trudged to the office of HICEM (an international subsidiary of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) on the rue de Paradis on a peak overlooking the city, and then downhill to the Joint Distribution Committee. Widely known as the Joint and based in New York, the agency had been founded in 1914 by wealthy American Jews to aid needy coreligionists overseas. Now its critical mission became one of rescue. It maintained an office in Marseille on the broad avenue of la Canebière, steps away from the feverish port where refugees flocked in fearful pursuit of any conceivable means of escape from Europe. Among them, time after time, came Sigmar and Trudi. Yet each time, confronting the chaos and competition, the endless waiting for visas and papers, and the bureaucratic delays caused by Vichy’s morass of new regulations, father and daughter returned to Lyon with nothing but the certain assurance they would have to journey to Marseille again.

They needed French exit visas, transit visas, and entry visas for admission to Cuba. Exit visas required application to the prefecture (the governmental agency responsible for administering national law on the local level) in the department or region where they resided, which for Lyon was the Préfecture du Rhône. At the discretion of the prefecture, they might well be required to apply to their local police for certificates attesting to their good behavior. They needed travel passes just to go to Marseille to pursue further papers, and once they got there had to apply to the Préfecture des Bouches-du-Rhône. This office, covering the department of southern France that included Marseille, had been delegated responsibility by the Ministry of the Interior to assign rare space on one of the very few ships available to refugees who managed to get their papers in order. If Herbert succeeded in purchasing their tickets, they might bypass the difficult step of obtaining in France the American dollars required to pay for the voyage. All the same, permits were valid for only a limited period, and if any expired before the rest were secured, rules required obtaining renewals or starting the process over again.

“They can just kiss my ass!” A shocked Trudi reported the first vulgarity she had ever heard from the lips of her father, who erupted after a rescue worker explained why the dossier of papers Sigmar believed was finally complete would still not suffice to permit them to leave.

Meanwhile, aid agencies suffered the same frustration and anger. HICEM valiantly struggled to coordinate the demands of consular offices, shipping firms, and the Vichy administration. But the agency’s efforts were hampered by a lack of funds, ships, and countries willing to grant admission to Jews, as well as by governmental inertia, indifference, and endless red tape. American consulates in occupied Europe ceased operations by the middle of June, and laws passed that month in the United States sharply limited the granting of visas. Under the pretext of security concerns that spies and subversives could sneak into the States as refugees, Jewish immigration was virtually forced to a halt.

Anti-Semitism in federal government offices even tarred the Jewish aid agencies themselves with suspicion of serving as secret tools for the Germans to maneuver Nazi agents onto American soil. But as the American Foreign Service Association later confirmed, “The official U.S. policy was that Jews were not to be granted American entry visas, as it would not be wise to upset any government that might become legitimate and important in Europe, and therefore a possibly valuable ally.” Consequently, between the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and war’s end in 1945, ninety percent of the visa quotas set aside for would-be immigrants to enter the United States from countries in Europe controlled by the Nazis went unfilled.

In the days that she wasn’t traveling with Sigmar, Trudi was put to work helping Alice in the tedious task of

ravitaillement

or provisioning, which entailed standing on lines in the continual hunt for food. In the apartment, the absence of crumbs emboldened the mice to the point that they showed up at the table for regular meals with the entitlement of family members. When Sigmar brought home a cat to keep them at bay, the cat learned to filch as well as the mice, brazenly snatching food from Alice’s hands before she could get the plates to the table. When the cat made off with the delectable treat of a slice of liverwurst that Alice had waited all day in the cold to obtain, it sparked not only tears of vexation, but also a permanent longing for that kind of sausage that none in the family would ever outgrow. When Trudi managed to snare the prize of a single egg, all five of them selflessly argued so much about who should eat it that over the days they genteelly procrastinated about its consumption, the egg went bad, and they had to throw it away. They tried to brew coffee from roasted peas, learned to live on a diet of yellowish turnips called rutabagas, and relied for lunch on a carrot or an apple, saving for breakfast their single slice per person that was their daily ration of a dry mix of grains masquerading as bread.

Janine (R) wears the Mulhouse insignia on her sweater as she poses with Trudi, Norbert, and the cat Munnele on the balcony of their Lyon apartment at 14, place Rambaud

.

But even here in the Unoccupied Zone, they were far from alone in their terrible hunger, with the Germans requisitioning the bulk of French food to ship over the border. Hunger became a paramount political issue. Across France housewives marched in food demonstrations, undermining the popularity of Marshal Pétain, the grandfather who purported to stand for traditional values yet failed to provide for the family’s supper. When stores lacked even what rations prescribed, starvation forced people to buy at inflated black market prices—as much as ten times higher than usual. Although this practice was technically outlawed, officials often had no choice but to close their eyes to it. Eventually, however, black marketeering offered the pretext for arresting those perceived as politically suspect, which proved useful in meeting Nazi quotas for both slave laborers and Jews to be deported east to feed the voracious fires of the camps.

The slang term

le système D

, from the verb

se débrouiller

—to manage resourcefully to straighten things out—summed up the finagling required for survival. When the opportunity came to buy something scarce, people snapped at commodities they themselves did not need just to resell or trade them for other things that they wanted. When, for instance, Roland and Roger stumbled upon the chance to obtain a cache of silk stockings, they pooled resources in order to buy it and sold them off by the pair at a serious markup. From the Vichy government, both Roland and Roger received a small monthly “refugees’ stipend” by virtue of not being able to go home to Mulhouse. Still, with increasing bravado, Roger traveled to outlying agricultural regions and returned with sacks of food that brought hefty profits on the Lyon black market. The money he made, for example, when he managed to come by a large wheel of Gruyère that he sold by the wedge carried them both for a number of weeks. Roland pawned the gold Baume & Mercier wristwatch that had been his proud father’s baccalaureate present, then seized upon any

petit métier

or odd job he could find in order to claim it again. He sold chocolate truffles made by the cousin of a friend of a friend, and besides grading papers for Janine’s employer, he rewrote a thesis for a Chinese graduate student struggling to put his ideas into French. “Anyone can live well with money,” Roland would observe. “The art is in living well

without

money.”