Crossing the Borders of Time (14 page)

Janine stared at the web of roads on the map spread out on the table and at the suitcases lined up like some ragtag army, ready to march, crookedly running the length of the hall. Her father was talking, looking at her.

War. Too close to the border here in Alsace. Hitler invading

. She heard only fragments of what he was saying, but sensed everything starting to topple around her. Her mind rushed back to Roland, to the green, lazy river, as if, starting over, she could take a different route home in order to enter a happier scene when she came through the door. She remembered the distant day she had outraged her father by sharing the bold theological news that it wasn’t really for eating an apple that Adam and Eve were exiled from Eden, but rather for their sexual exploits. Having only just left the arms of Roland, was she, too, now to be punished for trading kisses and indulging in love?

Wir wandern aus

. Again. But where could they go?

SIX

GRAY DAYS, PHONY WAR

P

ANIC DESCENDED ON

A

LSACE

during those uncertain days of early September 1939, as a nationwide mobilization called army reservists back to their units, workers hauled sandbags to bolster air raid shelters and windows, curfews abruptly clamped down on nightlife, and civilians made contingency plans for fleeing their homes—easy targets for shelling from over the Rhine. The banks shut their doors. The government declared martial law, advised hospitals to truck their patients out of the cities to safer, more rural locales, and banned international telephone and telegraph services, which added to the mounting fear and confusion. Strict new regulations called for carrying gas masks and pocket flashlights at all times and rushing to shelters when sirens were sounded.

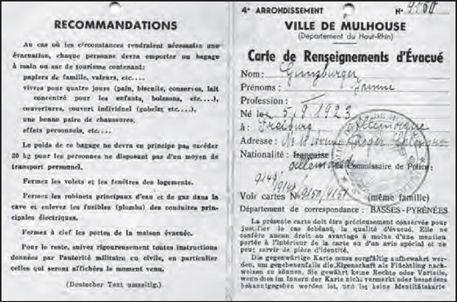

In Mulhouse, city officials distributed personalized emergency cards informing residents in both French and German what region would welcome them in case evacuation from Alsace proved necessary. Janine’s evacuation card, No. 9150, preserves the official instructions, among them the warning that the cards themselves were to be “preciously guarded”: Be sure to take along family papers and valuables, provisions for four days (bread, biscuits, canned goods, concentrated milk for the children), as well as individual cutlery, glasses, and blankets, and a good pair of shoes. The total baggage weight per person should not exceed 30 kilos [about 66 pounds] for those without personal means of transportation. Close shutters and windows, turn off the sources of water and gas, remove electrical fuses, and lock up securely. “For the rest,” it advised, “rigorously follow all instructions given by the military or civil authorities, particularly those that will be displayed when the moment arrives.”

The evacuation card issued to Janine by the city of Mulhouse in 1939 in anticipation of a German invasion over the nearby border

Despite such precautions, the situation remained tentative, a war of nerves with the Germans. No one seemed ready to say whether actual war was at hand or whether hope still existed that Hitler would relinquish his claim on the Polish city of Danzig, halt his eastern attack, and back down. The papers were filled with ironies that made it hard to assess the state of affairs. It was reported that the actress Norma Shearer, vacationing on the Riviera with the suave French star Charles Boyer and his wife, had been summoned by Hollywood to rush “home to filmland.” At the very same time, however, large advertisements proudly declared,

FROM SEPTEMBER 1ST TO 20TH THE WHOLE WORLD WILL MEET IN CANNES FOR THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL

. They promised “three weeks of splendor and enchantment” along the resort’s lively Croisette, lined by princely hotels and colorful Mediterranean beaches.

Bizarrely, a menacing letter from Hitler to French premier Edouard Daladier, warning that a “new bloody war of annihilation” would unfold unless his demands for land were accepted, appeared in the newspaper beside an upbeat ad from the German spa city of Baden-Baden. It guaranteed “a peaceful and hearty welcome and unequaled possibilities for rest and recreation” for clientele from abroad and assured potential guests that “despite certain reports about scarcity and quality of food,” meals and service remained as fine as they had been in the past.

Still, denouncing the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles as “intolerable” and bellowing fresh demands for Lebensraum, Hitler refused to withdraw from Poland. Consequently, on September 3, first England, then France reluctantly declared that Hitler left them no choice but war.

Interrupting their packing, the Günzburgers anxiously gathered around the radio that night to hear Premier Daladier’s emotional five-minute broadcast to the nation: “The cause of France merges with that of justice,” he said. “Frenchwomen and Frenchmen, we are making war because it has been imposed on us. Each of us is at his post on the soil of France in this land of liberty where the respect for human dignity finds one of its last refuges.” He closed with a rousing “

Vive la France!

”

Within hours, Hitler’s first unprovoked assault on the Allies—the sinking of the British ocean liner the

Athenia

—resulted in the deaths of 112 passengers, the majority of them women and children. With that, German Jewish refugees in Alsace confronted with new urgency the terrifying possibility of Hitler’s troops pursuing them from over the Rhine. Quick escape from the border region became their priority, even as war with their native country made their status in France an open question.

A German Army veteran, Sigmar faced a dilemma much like the one he encountered after the previous war, when he first attempted to settle in Mulhouse. To the French, he was German—mistrusted as an enemy, with no way to hide his name or his accent. To the Germans, he was a Jew—a stateless pariah and fair game in any territory he might be found. While prudence left him no other choice, moving from Alsace meant leaving the one part of France where he felt somewhat at home, where a Germanic name and dual national heritage were well understood and Jews well established. Thus, with a heavy heart, Sigmar studied maps, consulted friends, and made frantic arrangements to get Trudi home from her cousins in Brussels that weekend.

How sorely he missed the roomy Opel sedan he had been forced to give up to the Glatts! Transportation loomed as a serious problem, not just for the immediate family now, but also for his sister Marie and her longtime Jewish housekeeper, Isabelle (Bella) Picard, from whom she was inseparable. Both now in their sixties—one a widow, the other unmarried—they looked to Sigmar for their escape. Marie’s son Edy had already been called up to the French Army as a captain, while Lisette and their children were evacuating to a town in Burgundy known to Lisette from summer vacations. Marie’s only daughter, Mimi, married to a prosperous French Jewish silk merchant in Lyon, was staying put in her spacious apartment steps away from the grand place Bellecour. But Marie and Bella were afraid to go there, believing with Sigmar that hiding in the provinces would make them less attractive as targets, both of Germans and shelling, which they expected to start near the border at any second.

That Monday, with the first of what would become a full ledger of loans from relatives, Sigmar sent Norbert to buy a car to carry them south for fear that traveling by train, passport checks could invite trouble. But it was immediately apparent that the bright red Rosengart with the tall front grille in which Norbert returned could not possibly carry them all, let alone fit everyone’s barest essentials for an absence of unknown duration. It was the cheapest and smallest car produced in France at the time, mocked as resembling a soapbox on wheels.

The Rosengart was reputed to be the cheapest and smallest car produced in France in the late 1930s

.

(photo credit 6.1)

Sigmar stood mute in front of their building when Norbert called him downstairs to admire it, and he studied the small two-door coupe with glum disappointment. Then, still not a driver, he awkwardly climbed out of habit into the cramped backseat, where even sitting alone, he realized this one little car would not suffice. Never before a man to seek favors, now, looking toward a menacing future, Sigmar saw that the price of pride vastly exceeded his ravaged budget. Mentally, he leafed through his address book for someone who owned a car and might be willing to help them. He came up with one man, Joseph Fimbel, a teacher and Marist lay brother with whom he had slowly developed a friendship based on the hours they spent discussing religion. So many hours, in fact, that Alice suspected Monsieur Fimbel nourished a private hope of converting her husband.

But if his Catholic friend harbored such aspirations, it was a thought that Sigmar may have unintentionally fostered through his genuine interest in exploring the church’s mysterious spiritual beauty. Already in Freiburg, besides his regular visits to the old Catholic graveyard, he had loved wandering through the majestic cathedral, its air fragrant with incense, hundreds of white candles flickering prayers in the half-darkened vaults. He would listen, entranced, as the organist bobbed over his keys, the deep chords of immense pipes throbbing in the ancient stones under his feet. Sigmar stood with respect as his neighbors sank to their knees to speak with a God who had suffered their pains, and his hand gripped the burnished wood of the pews almost as if he truly belonged there.

And yet, expedient as conversion might have been at that hour—a test Jews had repeatedly faced through the centuries—Sigmar could not have imagined renouncing the faith of his fathers. His appreciation for the kingdom of God he saw expressed in the church was romantic, aesthetic, something apart from the Jew that he was, much as he loved Wagner’s

Ring

without reservation, ignoring the uncomfortable fact that the music’s creator had seen little value to the existence of Jews. Indeed, while it sometimes occurred to him that his own Creator no longer cared much for Jews either, Sigmar had been wont to slip out of the Freiburg Cathedral with the furtiveness of a wayward husband leaving his lover, ever chary of being spotted by

Herr Rabbiner

Julius Zimels, the immaculate rabbi who strolled through the town wearing dove-colored spats and a fine homburg hat. That the rabbi would sanction his ecumenical tourism struck Sigmar as doubtful, while he believed Monsieur Fimbel not only welcomed his interest, but also honored its limits. Their friendship was based on such firm and mutual regard for each other that, as Sigmar expected, the teacher readily agreed to assist him, all the more as he was planning to get out of Mulhouse with similar haste.

For Sigmar, the next pressing question of where to go involved such a gamble that he made a decision based on little more than a letter and Monsieur Fimbel’s convenience. Sigmar had received the letter a few months earlier from a former Freiburg acquaintance. The man was a cattle dealer who wrote of being comfortably settled on a farm he had bought on the outskirts of the small town of Gray in the dairy region of Franche-Comté, southwest of Alsace along the Swiss border. A Jewish mayor, Moïse Lévy—who was also a senator representing the Haute-Saône department of Franche-Comté in the National Assembly—governed the town of some six thousand people, he wrote, which contributed to a friendly atmosphere for refugees escaping the Germans. Beyond this information and the knowledge that Gray was less than four hours away, not far from Dijon and sited on the Saône River, Sigmar knew virtually nothing about it. Certainly it had the advantage of being much closer to all that they knew than their official evacuation assignment to the country’s extreme southwest corner near Spain, which Sigmar chose to ignore for the moment.