Crossing the Borders of Time (28 page)

“

Wer kann Deutsch sprechen?

” Who speaks German? the SS officer in charge of the convoy strode down the tracks shouting, as the cars were thrown open and the cowering prisoners blinked in the sunlight. Joseph Fimbel made the mistake of proving too useful. Once again, Brissinger says, he engendered distrust when actions inspired by a longing to help tragically backfired.

“What are you going to do?” Fimbel brashly inquired of the German, after translating an order for ten of the prisoners to climb down from the train and strip off their clothes.

“Shoot them,” the Nazi retorted.

“No! I beg you, don’t do that!” Fimbel cried out, trying to marshal reason to save them. “Look, these are very old men. What is left of their lives will already be short. Why shoot such old men?”

“Yes, of course, you’re right,” the SS guard said, his voice the essence of reasonableness. He ordered the original ten back on the train and pointed to ten of the youngest on board to climb down in their places to face execution.

“Take me instead! Take me!” Fimbel insisted, already seeing the blood of young lives staining his conscience. But the ten were dragged off, followed by SS men carrying pickaxes and shovels. Gunshots exploded the peace of the forest.

Those prisoners still conscious were pleading for water when the train reached Buchenwald, the notorious Nazi labor camp on the outskirts of Weimar where fifty-six thousand suffered and died. Among its eighty thousand survivors at liberation was Léon Blum, prewar France’s Jewish premier, who was blamed for defeat, condemned to life in prison by Marshal Pétain, and then, in 1943, turned over to Hitler.

Upon arrival, Fimbel’s seemingly lifeless body was stripped and his Marist ring yanked from his finger before he was piled on top of a cart of cadavers headed to the crematorium. When a fellow inmate noticed him moving, he was revived, only to be sent with five hundred others to a grueling satellite camp to work in a salt mine where life meant beatings and torture, starvation and illness, topped off with a month-long death march in 1945, as the Nazis realized the Allies were coming.

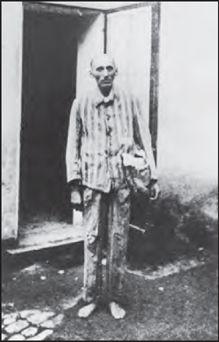

On September 11, 1944, when the American Army liberated Gray, clocks were restored to their proper French time. Three months later, the local committee of the liberation elected a Jew to serve as mayor. Joseph Fimbel, freed by Soviet soldiers, returned to Gray on May 23, 1945, weighing eighty-six pounds: the hollows of hunger were caves in his cheeks, and his shriveled skin was waxy and yellow. Like most of the clothes he had worn through his life, his striped camp uniform failed to cover his long, bony limbs. But Joseph Fimbel insisted on wearing those same wretched rags of the camp on his first night back in Gray, which he spent on his knees through long hours of prayer at Notre-Dame’s altar. He later arranged for a plaque to be placed at the entrance to the chapel in grateful dedication to Mary, the Holy Mother whose compassionate smile and promise of grace had sustained him throughout his descent into hell.

This plaque would prove his only memorial in Gray, besides the portrait that hangs in the town hall gallery of mayors. On May 1, 1954, however, a decade after his arrest by the Nazis, the French government honored his actions by naming him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Fellow deportees from the Buchenwald subcamp appeared at the ceremony, expressing appreciation and lending witness to the courage and selflessness of Joseph Fimbel’s service to them in the face of tremendous personal peril. The grand rabbi of Lyon sent a message thanking him for individually saving at least sixty Jews, and the Germans, too, would later honor him for his postwar endeavors promoting forgiveness and friendship between the two countries.

The Catholic mayor of Gray, Joseph Fimbel, was deported as a political prisoner to the concentration camp of Buchenwald near Weimar, Germany

.

(photo credit 10.1)

“When Fimbel returned from Buchenwald, that’s when people recognized the work he had done, because during the Occupation, there was always a certain suspicion,” André Fick said, describing the day the Alsatian mayor finally won the respect he deserved.

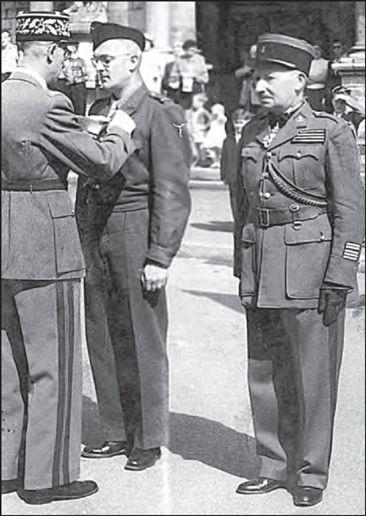

André also gained recognition, in 1958, when he was awarded the Military Cross of the Resistance in a ceremony on the town hall plaza. Yet, despite the passing of decades and Fimbel’s death in 1978, it remained his keenest desire for Gray to pay homage to the former mayor by dedicating a street in his name. When I volunteered my support to such a campaign, his wife shot him a look of definitive warning. This was clearly a road they had traveled before, and Marguerite did not intend to go back where it led or to revive the uncomfortable feelings the issue provoked for their neighbors, many of whom apparently still nurtured conflicted views on Mayor Fimbel’s performance in Gray under the Nazis.

André Fick was decorated with the Croix de la Résistance in 1958

.

(photo credit 10.2)

“Moïse Lévy has a street named for him, and he did far less!” André complained to his wife. A childlike tone of indignation made his voice quaver. “Moïse Lévy was the administrator of Gray for a much longer time, but in an

époque

that was

bien banale

, humdrum and peaceful. To do what Fimbel did for four years under German occupation, to save so many people—that deserves more!”

Marguerite stared at him and did not reply. The petite white-haired lady was a serious force. After waiting in silence, André turned to me and threw up his hands. “My wife does not want me to pursue it, and I cannot go against her,” he said. “I would have liked to do it out of fidelity to him—my patron, my director, my teacher—out of gratitude to him.”

Near sunset on that day of Gray’s races in 2001, after the last contestant had crossed the line, André Fick took me to the top of the town to the Basilique Notre-Dame. In retirement, he had become the church organist, and he was pleased when I asked to hear him play. Through the organ, he had continued serving the town while finding his personal form of devotion to Mary—not the one he imagined at twenty-three, in the thrall of his mentor, but one that he could fully express with a wife at his side. We arrived just as the priest was locking the doors, but with dispensation graciously granted, Marguerite and I followed her husband up the spiral stone steps of the fifteenth-century church into the organ’s high vaulted home. With little ado but evident pride in his church, André started to play, drawing the stops and pressing the keys. Music swelled through the nave, and the humming chords of his hymn rose through the restored bell tower to drift in the twilight, surprising the town that was spread out below us, preparing for dinner. His impromptu recital was a peaceful close to a day that had wakened to the tumult of athletes speeding through narrow Renaissance streets, crowds cheering at corners, and loudspeakers blaring. That evening, I would leave feeling grateful for the quiet bravery of all the Ficks and the Fimbels—people who risk their lives to wrestle with power in places whose names are not even footnotes in history’s pages.

ELEVEN

THE SUN KING

O

N

C

HRISTMAS

D

AY OF 1940

, Roland Arcieri happily found himself alone in Lyon with a room of his own, the princely sum of 30,000 francs in his pocket, and the world at his feet. He was twenty years old when he maneuvered off the bus from Villefranche, and despite the burden of all his possessions, he felt buoyed by a new and electric feeling of freedom. The rest of his family had left Villefranche to move back to Mulhouse just the previous day. But he felt no self-pity as he crossed the bare ground of the place Bellecour at a time when even the Sun King looked lonely and cold atop his bronze horse in the square, and everyone else was celebrating with family members, making do with such feasts as rations allowed. Rather, as Roland prowled the city, now quiet and empty, he viewed its streets as his for the claiming. He discovered it all with the fresh eye of youth and a conqueror’s glee, undoubtedly equal to any sense of triumphant arrival that even King Louis XIV had known.

Roland surveyed his domain in leisurely fashion. “No point in rushing,” he was known to joke with a shrug of the shoulders. “We’ll all arrive at the end of the month at the very same time.” He paused on the sidewalk beyond the barren sweep of the square and its simple border of skeletal trees that left it begging for more decoration, put down his bags in front of a bookshop, and peered in the window. The shop was gated and closed. But as Roland stared into the gloom, it was almost as if he might already catch a glimpse of himself perusing book titles—works of biography, history, and literature, and even the odd, naughty bit of

grivoiserie

—browsing, unhurried, through stacks of books laid out on the tables, no longer bound to run for the bus to Villefranche at the end of the day.

Ah, the pleasure of knowing his time was his own, finally freed from his father’s ten p.m. curfew and being called to account for every coin that fell out of his pocket. He was more than ready to dive into life,

la bonne soupe, la grande liberté

! Never mind his tight student budget or his father’s well-meaning yet tedious warning that the money he gave him was intended to last for two or three years. He took note of intriguing bars and cafés that he had never before had time to explore and permitted himself to thrill in the knowledge that everything strange would soon be familiar. Then there would be a new kind of pleasure—feeling at home in this elegant, cosmopolitan city, a man in the world, making his way. At last his life was truly beginning.

He had come to Lyon for the ostensible purpose of studying law. This is what his father believed, and he therefore tried, at least for a while, to believe it himself. For the previous year, while commuting to classes, he had also fulfilled his military service by attending twice-weekly officer training sessions and made the one-hour trip to Lyon by bus every day. His family had decamped from Mulhouse to Villefranche six weeks after war was declared, when the textile firm that employed his father and uncle acted well in advance of any invasion to shift some operations out of Alsace. The firm had mills in Villefranche, a small commercial, industrial town northwest of Lyon, chiefly distinguished as capital of the Beaujolais winemaking region.

Here, as part of the company’s managerial class, the Arcieri brothers resettled in style in a spacious villa just a bike ride away from a stretch of the Saône that was verdant and tranquil. The house was not far either from the lively main street, the rue Nationale, which rolled over a hill through town like a great wave, bereft of trees or even the simple appeal of a planned public square. Except for the local church and a few houses of historical merit, the street’s unbroken façade of four-story buildings with shops on both sides included little of any real interest or beauty. Still it drew out the crowds for the ritual promenade in the evenings, which served here, also, as prime entertainment with the promise of people meeting each other.