Crossing the Borders of Time (24 page)

Indeed, Mom never said anything to suggest that the French had ever collaborated with Hitler, while she claimed to have encountered more blatant anti-Semitism in the United States than she had

personally

experienced in France, or even in Germany, for that matter. To me, this stark, unfamiliar assertion raised the threat that Jews were at risk in America also, and I could not help but cringe every time she made it. I had no grounds to refute the way that she sidestepped accounts of French persecution, maintaining instead that the French, victims themselves, had been forced in the 1940s to yield to the will of the conquering Nazis. She could no more blame France than bury her love for Roland.

In recent decades, scholars have offered more damning accounts, showing that although many French harbored no particular hatred of Jews, the French government under Pétain zealously leveled sanctions against them. What Pétain described as collaboration, a viable means of coexistence with Germans within France’s borders, quickly gave rise to endorsement—emulation, in fact—of policies aimed at destroying the Jews. In some cases, the Vichy administration readily jumped forward, enacting sanctions even before the Germans required them, while some of the measures the French imposed early on were even harsher than parallel statutes the Nazis devised.

Between the Germans and Vichy, the situation for Jews in both parts of the country began changing quickly. Neither zone represented a reliable haven for a population of Jews that had swelled from 150,000 in 1919 to 350,000 by World War II, among a total French population of 40 million. Another 400,000 Jews would pass through France in those years as stateless refugees hoping to find safety elsewhere, only to find themselves caught in the grip of the Vichy regime, which willingly handed off many thousands to the Germans. On a psychological level, how could the French despair for Jews deported to camps as long as 1.5 million of their own men were being held by the Reich as prisoners of war, most not free to come home until Hitler’s defeat?

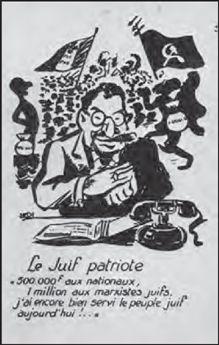

A representative anti-Semitic cartoon of the Vichy era depicts the hooked-nosed “Patriotic Jew,” apparently a financier, congratulating himself with these words: “500,000 francs for the nation, 1 million for the Jewish Marxists. I have served the Jewish people well again today.”

(photo credit 9.3)

That August 1940, Vichy unleashed one of its first assaults upon Jews by repealing the Marchandeau Law, which had outlawed racist attacks in the press. This enabled Hitler’s propaganda machine to begin feeding the public the same sort of anti-Semitic vitriol it had spewed years before to incite the Germans. The date of this action, August 27, sent chills through my mother, as did the date two months before when French prisoners were marched out of Gray on June 27 to be sent into captivity over the Rhine. “It figures—you know today’s date,” Janine remarked as she and Trudi stood on the street sadly watching them leave.

Yes, in the course of my research into her story, I, too, have been struck by how often that number she dreads reappears. On September 27, 1940, as Germany signed a Tripartite Pact with Italy and Japan aimed at keeping America out of the war, the Nazis called for a census of Jews and imposed the first anti-Jewish ordinance on the Occupied Zone. It would not go unnoticed that the date of the measure came exactly 149 years from September 27, 1791, the day that a vote of the National Assembly made France the first country in Europe to offer Jews full citizenship.

It was March 27, 1942, when the first German transport sent more than a thousand Jews from detention in France to death at Auschwitz. On May 27, 1943, the National Council of the Resistance first met in Paris and, led by Jean Moulin, voted to place its confidence in de Gaulle to restore the Republic. But the daring Moulin—soon captured and brutally tortured by the Gestapo in Lyon—died in custody on a train bound for Germany. On July 27, 1944, the Germans moved to crush the Resistance, gunning down five French patriots in front of a Lyon café on the place Bellecour, where their bodies were left sprawled on display as a warning to others. A memorial marking the spot where their blood stained the sidewalk lists the names of all the Nazi camps that befouled the countries of Europe. Among them, the death camp of Auschwitz, where two million captives were murdered, was liberated by Soviet troops six months after the Lyon slayings. The date, January 27, 1945, is now annually observed as International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Is there some benefit, then, to fixing one number, as my mother has done, fearing one day a month as being portentous? The answer could only be yes if it left twenty-nine others for breath to come easy, but that was not the case here. Vichy imposed two broad-ranging

Statuts des juifs

on the so-called Free Zone on October 3 and 4, 1940, banning Jews from many public and private professions and placing them in a lower position under French law. Foreign-born Jews could be arrested and interned in “special camps” or assigned to distant compounds under surveillance, a ruling that carried grave implications.

French Jewish leaders reacted with respectful but vigorous protests, noting that Jewish citizens remained, as ever, faithful to France. In a statement decrying the measures, Chief Rabbi Isaiah Schwartz called for equality and affirmed that “no values could be dearer to us” than those of “work, family, and homeland” that Vichy had chosen to define its regime. “We will respond to a law of exclusion by unswerving devotion to the homeland,” the rabbi wrote to Marshal Pétain, who did not respond. Like Alfred Dreyfus decades before, French Jews now refused to allow their victimization to shake their sense of themselves as true citizens, loyal to country. In 1940, moreover, on the defensive again, French Jewry insisted that citizenship guaranteed them rights of protection that the stateless refugees who had swarmed over their borders could not hope to claim. And so, much like my mother acting on instinct, keeping faith with that country and pretending to be what she wanted to be, the Jews of France proudly asserted their right to be French. They needed to trust in France as their savior, or else they had nothing.

TEN

CROSSING THE LINE

S

IXTY-ONE YEARS

from that summer in Gray when my mother peeked through the shutters on the avenue Victor Hugo to watch German soldiers in swimsuits march to the river, I arrived in August 2001 to find a muscular swirl of triathlon runners and cyclists jolting its drowsy Renaissance streets. In the Saône’s choppy waters, what appeared to be seals were swimmers in wet suits, shiny and black, racing downstream. And as crowds cheered contestants from all over France, a message of life and renewal rang through this town, always linked in my childhood to stories of war.

My appointment that day was with André Fick, a former top aide to Gray’s Mayor Fimbel. He was then eighty-four, and as racing cyclists swarmed through the town, I was surprised to meet him astride a bike, too, cruising his street and gallantly watching for me in case I had trouble finding his house. I’d remembered his name from wartime documents my mother had shown me, letters on which his official signature had worked like a lifeline during the years the Germans were there. Without André Fick, my own existence would have been doubtful. Yet in the instant we met, I disappeared, for he leaped over years and mistook me for Janine.

“Ah, it’s wonderful to see you,” he said, his tone unusually formal for an avowal that proved disarmingly candid: “

Vous savez, j’ai toujours eu le béguin pour vous

.” You know, I’ve always had a crush on you. He clasped my hand, reclaimed Janine in my eyes and my voice and, lured by memories, slipped through a chink in time to a faraway moment when living in danger brought depth to relations. Behind heavy glasses, tears brimmed in his light blue eyes, and for one selfish instant I wanted to be her, my mother, the source of a dream he had never forgotten.

The son of a Mulhouse grocer, André Fick had been a devoted young Marist who studied and taught in Fimbel-run schools. Drafted into the French Army on the eve of the war, like so many other Alsatians he avoided going back home after defeat in June 1940 for fear that the Germans would force him to fight for the Reich. Instead, he eagerly followed Monsieur Fimbel to Gray, where, at just twenty-three, he took on the job of city liaison to the German command during more than four years of harsh occupation.

In his own written account of that difficult period,

Gray à l’Heure Allemande

(Gray in the time of the Germans), André Fick tells how the forces that occupied Gray gave shape to defeat for its downhearted people. For each, he says, the ordeal inevitably became something different. Some lost all that they had in the bombings and fires and dwelled on the shaky edge of existence. Some suffered the absence of a husband, a brother, a son, or a father imprisoned by Germans in mysterious camps. Many, especially women, were crushed by the burden of scrounging for daily subsistence, while others cunningly worked the black market, growing wealthy by milking the hunger of neighbors. Some were resigned, accepting the long Occupation with stoicism. Others believed resolutely in Marshal Pétain and that he would do the best for the country. The thirst for liberty and a gut-deep revulsion provoked by the Fascists prompted some, but not many, to risk their lives and join the Resistance. Others crept into the underground fight less for the aim of subverting the Nazis than as a means to evade the roundup of Frenchmen condemned to labor over the Rhine. With no way to guess how long the domination would last, fear and powerlessness weighed on the town like a low-lying fog.

The rules under which they endured, Fick recalled, multiplied daily in inverse ratio to the dwindling food in their larders.

Verboten

, forbidden: the right to assemble in public in groups of more than three people.

Verboten

: displaying the humbled French flag or French decorations.

Verboten

: photographing the exterior of any buildings or listening to foreign radio stations, especially London’s.

Verboten

: singing the “Marseillaise” and engaging in any political action.

Verboten

: to travel without official approval.

The problem in Gray was the same one confounding local authorities throughout the Occupied Zone, required under the armistice “to conform to the regulations of the German authorities and collaborate with them in a correct manner.” But what did that mean? Among the Graylois, citizens viewed collaboration with an added measure of dubiousness based on the fact that Mayor Fimbel and his assistant were native neither to Gray nor even to the Haute-Saône department. As Alsatians, moreover, both spoke fluent German and seemed quickly to win the trust of their masters.

To the dismay of the people, propaganda posters papered the walls of the town and encouraged its men to enlist for German factory jobs, and by the

Kommandant

’s orders, each issue of the local newspaper ran similar ads. “An end to the hard times!” the text declared. “Papa is earning money in Germany now!” And yet the Germans undermined their recruitment campaign with other posters openly hinting that their own men in Gray would usurp both the love and the hearths the French left behind: “Abandoned people, place your faith in the German soldier!” A handsome, uniformed

Wehrmacht

officer smiled from these posters with contented French children embraced by his arms. Small wonder that the volunteer rate proved so unsatisfying that by 1943 the Nazis would resort to forcing the French to work in German factory jobs, to stand in for their laborers sent into battle and thereby step up production of war supplies.

Still, recognizing the potential for German soldiers to compromise Gray’s lonely women, the town’s celibate mayor reluctantly acceded to the

Kommandant

’s order to set up a brothel. Monsieur Fimbel saw to it that prostitutes were imported from Dijon and Paris and that the bordello was furnished and kept sanitary. Costs were charged to the maintenance of the German occupied forces, with the bills to be paid by the people of France. But after the war, there would still be a handful of women, native to Gray, publicly shamed for fraternization. Among more than ten thousand other Frenchwomen later accused of “horizontal collaboration” with German soldiers, they were dragged to the city hall plaza and forced to submit to having their scalps entirely shaved.