Crossing the Borders of Time (22 page)

“Yes, yes,” Alice politely agreed, impatient to drive on, to rush to the shelter. “We must all count our blessings.”

When they reached the top of the hill, and the driver pulled up in front of their building, Alice handed the keys to Marie and told them all to go in without her: she would go search for Sigmar. It was characteristic of her relationship with her husband that she kept all intimate moments and all expressions of feeling between them totally private. Indeed, though she saved many boxes of letters and postcards from friends and admirers, leaving them for me to discover, when she reached her nineties she contrarily destroyed all the love letters and notes that Sigmar had sent her during their short engagement and very long marriage. “Those letters are personal,” my grandmother said, unapologetic, and she could not be dissuaded from feeding them to the random gluttony of her building’s incinerator. Like doves shot out of the sky, they fell fluttering down the cold metal chute in the hallway, straight to the fiery maw in the basement.

What happened when Alice ventured into the Ecole Supérieure de Jeunes Filles to seek out her husband among the displaced and new homeless of Gray is therefore a secret. Neither Alice nor Sigmar ever discussed it, but the girls and Marie leaned out the window to peer into the street and saw the couple pass through the gates of the schoolyard and slowly walk toward them.

Sigmar’s suit jacket was folded over his left arm, his shirt and trousers were grimy and wrinkled, his shoes were stiff with mud from the river, his hat was battered, and he needed a shave. All the same, his right arm was bent at the elbow, and Alice’s forearm rested on his, as if they were strolling down the Kaiserstrasse on a Sunday in Freiburg. Except now this street too, like the rue du Sauvage in Mulhouse and countless others in Europe, was called the Adolf-Hitler-Strasse; they themselves were in occupied France, along with the Germans; and before very long they would have to make plans for fleeing again. At the moment, however, they both seemed content just to walk side by side, not even talking, until they reached the door of their building, where Sigmar glanced up to the second-floor window at his daughters and sister—their faces like angels above him—watching and smiling.

“Sigmar, Baron von Ihringen,” he announced himself to his female audience with click of his heels, a sweep of his hat, and the hint of a bow. Then he indulged in a grin and the wave of a hero home from the war, and he opened the door for his giggling wife and entered the building, as Janine and Trudi flew downstairs to greet him.

NINE

A TELLING TIME

“G

IVE ME YOUR WATCH

, and I’ll tell you the time.” That was the joke on the street that wryly summed up for the occupied French how the victorious Germans viewed coexistence. But the time the French got from the Germans was not even theirs. The Germans advanced French clocks by an hour to match the time in Berlin, their bells all tolling together the time of the Führer. It was the

Nazi-Zeit

on an hourly basis.

For Senator-Mayor Moïse Lévy, who had held one city office after another for almost a half century, time was quite simply up. On July 20, 1940, the day that Gray marked the completion of temporary repairs to the mutilated bell tower of the church by crowning its flattened roof with a bouquet of fresh flowers, the German military authority removed him as mayor and named Joseph Fimbel as his successor.

The Jewish official was out of town when the announcement was made. As senator of the Haute-Saône, he had left in early July to participate in the National Assembly meeting in Vichy that would grant full authority to Marshal Pétain. The elderly general had chosen Vichy—far from the borders and blessed with hotel rooms—as the seat of his government in exile from Paris. Before long, his collaborationist regime would become synonymous with the name of the spa, and the Unoccupied Zone would be dubbed the

Zone Nono

, once the French understood that “Free Zone” was just a misnomer for an illusion.

Convening that summer, however, the legislators still hoped to preserve what they could of French self-rule. They arrived in Vichy in a furious temper, not only shamed by the debacle of total defeat by the Germans in battle, but also enraged by what they condemned as new treachery at the hands of the British, their own former allies. In the first week of July, alarmed by the French armistice with Hitler and fearful that, as a result, the Germans would seize control of French warships, Churchill decided he had no choice but to destroy the French fleet—a defensive move he would later acknowledge was “unnatural and painful.” With Operation Catapult, the British attacked French ships anchored off the coast of Algeria at Mers-el-Kébir and at other ports, killing more than one thousand two hundred French sailors and wounding hundreds of others. The fact that the British wreaked so much destruction helped to drive the horrified French farther into the arms of the Germans.

“France has never had and never will have a more inveterate enemy than Great Britain,” Pierre Laval, Pétain’s deputy, told the senators meeting at Vichy on July 4. “We have been nothing but toys in the hand of England, which has exploited us to ensure her own safety.” The only way to restore France to its entitled position, he urged, was “to ally ourselves resolutely with Germany and to confront England together.” The following day, stung by betrayal, France broke off diplomatic relations with Britain.

On July 10, gathering in the all-too-appropriate venue of the spa’s Grand Casino, the Assembly gambled away French citizens’ freedoms. The great-grandson of the Marquis de Lafayette stood among 80 parliamentarians opposing the motion, but 569 others fell into line with Laval and Pétain and voted to change the constitution. Now France turned on itself, blaming its downfall on disease from within. Its weakness resulted from moral pollution encouraged by the suspect, secular, and foreign influences of the Jews, the Freemasons, and the Bolsheviks; this was exemplified by the Socialist Popular Front of Léon Blum, who had served in 1936–1937 as France’s first Jewish prime minister. Or so it was charged. Albert Lebrun, the ineffectual president of the Third Republic, ceded power to Pétain without resigning. And in a sharp right-hand turn, the Assembly empowered the marshal to impose a new constitution by personal order. That evening, this man who had started his life as the son of a farmer and rose to glory in old age issued three sweeping decrees that anointed him chief of state, granted him total control, and adjourned the National Assembly indefinitely.

Like a strict but well-meaning grandfather, Pétain would impose discipline on a nation of unruly children led astray by questionable friends and now brought to heel with a new set of goals. Liberty, equality, fraternity—the old trinity of democratic France’s soaring ideals—gave way to a new triumvirate—work, family, homeland—that Gaullists would mock as already a failure. Its status, they said, amounted to this: “work: unobtainable; family: dispersed; homeland: humiliated.” It fell to the Germans, with Pétain as their front man and doddering puppet, to secure the foundations of a demoralized, bitter, and teetering France. The answer they found was totalitarianism.

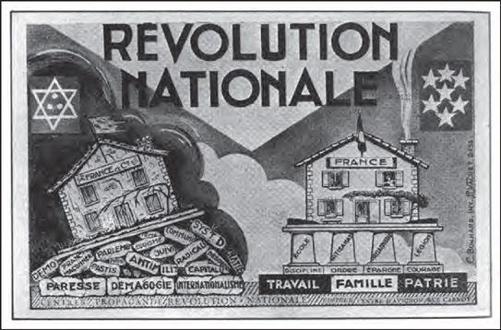

Pétain’s Révolution Nationale lumped together Jews, Communists, Freemasons, and the influences of laziness, drink, and egoism as responsible for the fall of France

.

(photo credit 9.1)

In the third week of August, almost a month after Moïse Lévy attended the meeting in Vichy, black-booted German soldiers barged into the fine yellow mansion of Gray’s former mayor across the street from the promenade des Tilleuls. He needed no explanation when the

Wehrmacht

officers brushed him aside and without invitation rudely proceeded to tour all the rooms, jotting down notes on their tasteful appointments. Then he received an order in writing: he had twenty-four hours to give up his home, fully furnished and outfitted with all its linens, dishes, and silver. The next day, as men in the park met to play boules, city firemen pulled a red truck in front of the house to help Monsieur Lévy remove those personal items he was permitted. But only when the Germans arrived, prepared to add pressure, did he come out the door, ashen and feeble, leaning on the arm of an aide, while tearful townspeople gathered to watch him depart.

Mayor Möise Lévy’s familial home at no 1 de la Grand Rue was confiscated by the Germans and turned into a residence for

Wehrmacht

officers

.

(photo credit 9.2)

Throughout September, remaining in town in stopgap lodgings though relieved of his duties, he would frequently visit town hall to keep up with events. In early October he would move to Paris, occasionally sending contributions to Gray for his pet social projects. But he would never again return to his birthplace except to be buried in Gray’s Jewish cemetery—a locked enclave on the outskirts of town, where visitors only rarely seek entry to add a small stone to the now ill-tended grave sites as custom prescribes, as a tangible token of eternal remembrance.

Near a wall sprouting patches of lichen and moss, the Lévys’ imposing family tomb records in marble Moïse’s many achievements:

Sénateur-Maire de Gray, Vice-Président du Conseil Général de la Haute-Saône, Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur

, and

Commandant de Mérite Social

. It also includes a memorial to his son, René Baruch Lévy, a chemist who was thirty-six in 1943, when he was deported to a Nazi death camp, seven months prior to the death of the mayor.

“

Assassiné par les Allemands au camp de Birkenau

,” is engraved on the shiny gray stone to remember René Lévy’s murder at the hands of the Nazis. “

Mort pour la France!

” Dead for France! The same words are also inscribed on a monument that lists him among twenty-three other Jewish Graylois deported to death camps, all lacking graves. An Yvonne and a Lucie, a Marcel and a Louis, a Paulette, a Clarisse—all dead at Auschwitz, all of them honored as dying for France, not victims but martyrs ennobled through sacrifice, as if willingly made in the name of their country.