Daily Life During The Reformation (21 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

As church services were disrupted and icons destroyed

everywhere, Felipe II, residing in Spain, ordered his general, the duke of

Alba, to transfer his army from Italy to the Netherlands to quell the uprising

by any means. He was given a free hand and arrived in Brussels August 22, 1567,

at the head of an army of 10,000.

Alba’s brutal tactics against rebels and reformers caused

about 100,000 people to flee the country for Germany and England. Alba and his

Council of Blood tortured and murdered anyone accused of treason against Spain

or heresy against the Church. He plundered towns to pay his army and raised

taxes to 10 percent on all sales, further inciting a furious public. The

Inquisition dealt with heretics sending them to death and confiscating their

property. The nobility were not immune. The atrocious suppression secured the

south for Alba but only served to reinforce the will to fight in the more Northern

provinces.

The 80 Years’ War for Dutch independence began in 1568 as a

Protestant Dutch uprising to throw off the rule of Spain and its Catholic

Inquisition.

SEA BEGGARS

In the 1550s and 1560s, violent gangs of hungry people

began wandering the country robbing and plundering. Often monasteries and

clerical travelers were their targets. By the latter half of the 1560s, they

were known as the sea beggars. They attacked Spanish soldiers whenever the

opportunity presented itself, and at sea they proved to be more successful than

on land. They sank Spanish vessels and also those of other nations. On July 10,

1568, they attacked and defeated a Spanish fleet. The feared sea beggars hated

anything to do with popery and Spanish rule.

Mixing with the local population, they quickly sparked

rebellions against the so-called Iron Duke (Alba) in town after town and spread

the resistance southward.

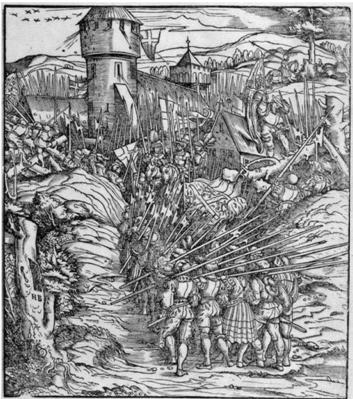

Surprise Attack on Maestreicht.

SPANISH FURY

Alba was dismissed from his command in spring of 1576; the

king of Spain had exhausted his finances, and without supplies (except those

stolen from the Dutch people), and their pay long in arrears, the Spanish

soldiers mutinied. In a frenzied rage, the soldiers ransacked Antwerp, Europe’s

leading commercial city and brutally slaughtered some 8,000 citizens over a

period of three days. Huge numbers of people fled, and anyone who remained and

had nothing with which to placate the furious soldiers was executed on the

spot. Houses of wealthy merchants were stripped and burned, their owners

grateful if they managed to escape with their lives.

News of the incident, known as the Spanish Fury, incited

the populace to fever pitch in their hatred of Spaniards. The determination of

the Dutch to resist occupation was demonstrated at Maestreicht (Maastricht) in

a siege that lasted four months. Two thousand soldiers held out against 20,000

Spanish troops. When the Spaniards broke through the walls, they slaughtered

about 10,000 inhabitants.

Rebellion

in the North

During these struggles with Spain, life and property were

far from secure as Spanish troops pillaged, the Inquisition sought victims, and

high taxes imposed on the people were used to pay their oppressors. Periodic rebellions

broke out in many places. A national leader was needed, and one arose in the

person of William I of Orange.

Appointed governor of Holland by Felipe II in 1559, William

joined both the Calvinist faith and the revolt against Spain. His leadership

inspired the Dutch with a new lease on optimism and determination to throw out

the foreigners who governed their country.

Seven Northern provinces rebelled and declared themselves

independent in 1579, becoming the Protestant United Provinces of the

Netherlands (Holland). The southern provinces (Belgium and Luxemburg) remained

with the Catholic Church, dominated by Spain. Meanwhile, throughout the long

struggle for religious and political independence, the common people of the

Netherlands attempted to live a normal life.

CHILDREN’S EDUCATION

After attending the local communal school, children went to

Latin schools that had changed their emphasis from a religious to a secular one

as the Reformation advanced. Education was primarily a privilege of the moneyed

classes, and young men between ages seven and twelve were sent off to boarding

schools in the larger cities. A good education was important for the individual

but also, in the Dutch view, provided a benefit to society. Those boys not

suited for training in the Latin schools took up apprenticeships to become

bakers or craftsmen.

DIET

Rye bread was a staple of the diet, its price and quality

regulated by city officials. The well-to-do ate white bread that cost more.

Regulations prohibited bakers from making pastry, pies, cakes, and cookies;

this was the exclusive job of other guilds. Although life was reasonably

prosperous for some, for those people whose houses and lands were ravaged by

Spanish troops and brigands, any kind of bread would do.

In the country a kind of soup was made of many different

kinds of vegetables, chopped and cooked with stale bread and broth (potatoes

were not known at this time). Such a mush would be simmered over a fire in a

large pan known as a cow kettle. Meat, usually pork, was sometimes added to

this. Only the wealthy ate fowl and game (unless they were poached) because

these foods were too expensive for most people.

At Christmas, a special cake would be made consisting of

pears or quince, almonds, curds, and raisins mashed together with sugar and

cinnamon. To this mixture, butter and several egg yolks would be added.

WINTERTIDE

In the Netherlands as in other parts of northern Europe,

life from day to day proved hardest in times when a severe winter settled over

the land, and temperatures plunged below freezing and remained there for weeks

or months. To keep the fire going was a real effort; as wood became scarce, the

countryside was scoured for anything that would burn, and those that had wood

to sell charged a price that was far too high for many. Hundreds of poor people

perished in the countryside and in their homes from hunger or freezing. Fodder

for farm animals was scarce during such times, and they died in the thousands.

Wolves roamed freely in the village streets looking for food. Ships locked in

the ice in the harbors brought trade to a standstill as supplies of local and

imported grain dwindled, and prices skyrocketed. Since dealers in grain

sometimes refused to sell if they were expecting prices to go up, citizens

rioted in the streets, and bakers and grain depots were stormed and decimated.

The poor farmer, who managed to survive the winter with his

chickens, eggs, cow and sheep, and his home-grown dried vegetables, was often

robbed and cleaned out and, on occasion, even killed by vagabonds, gypsies,

roaming soldiers, deserters, lepers, and tramps, anyone who was homeless and on

the move. Before going on to the next place, they sometimes set fire to the

farmhouse and warmed themselves.

HOUSES AND FURNITURE

There were no street numbers, so houses needed to be

identified in other ways. A red boot hanging above the door, a pair of gilded

tongs, or the house “on the right of the one with the picture of a horse,” and

so on made finding the dwelling in question easier. Inns and taverns had their

distinctive signs hanging outside, often carved in wood.

Houses had both stone and wooden facades in the cities,

many with thatched roofs. In poor houses, an open fire in the middle of the

room had a large kettle suspended over it, used for simmering oatmeal,

vegetables, or fruit.

People who worked at home, such as tailors, shoemakers, or

cabinetmakers, used the front part of the house as a workshop or showroom. Such

rooms were unheated and cold most months of the year, so the owner warmed his

hands by retiring on occasion to the inner room where stood a fireplace. There,

he sat on a stool or a bench. In some cases, the back of the bench would be

reversible so that he could face the fire or sit with his back to it. On the

bench might be a sheepskin, a cushion, and even a footstool for more comfort.

But people in general were used to uncomfortable furniture, and for most a

plain board with four legs was generally what they utilized. Padded and

comfortable armchairs were unknown, and the floor would do if nothing else were

available. Worshipers even brought their own folding chairs or stools to

church.

In lower class homes, most utility items were homemade,

such as a barrel chair with the upper half of one side cut away, half filled

with cushions, and giving back support. Another item of furniture might be just

a log split in half with two wooden legs at each end.

The fireplace was the main source of heat in the inner room

of the dwelling where wood and mostly peat were burned. Within the fireplace

were the andirons, and blocks of peat (from the marshes) and wood were put on

top of them, so the chimney would draw well. The women often stood in front of

the fire with their skirts gathered up, so the warmth could go up to their

bodies. Suspended from a crossbar in the chimney of the fireplace was an

adjustable hook to hang pots containing food at different levels above the fire.

A spit for roasting chicken or duck over the fire would be found in most homes

along with other utensils such as a metal or wooden porridge spoon for stirring

and serving. Other implements for cooking included a very long-handled frying

pan (so one could stand back from the hot flames and fry an egg), tongs of

various shapes and sizes, metal tripods, and bellows.

A clay fire bell covered the fire overnight so that there

might still be hot embers in the morning, which could be used to restart the

fire. If not, then a flint was struck against metal to create a spark in a

tinder box filled with singed cotton that was nourished along by blowing on it.

In the interior room of a middle class house was the

feather bed, about waist-high off the floor, covered by a blanket and

surrounded by curtains with a canopy above. Some shelves would be along a wall

near the fire for dishes, along with a cabinet for storage, a few wooden

stools, a bench or two with cushions, and a folding table against a wall when

not in use. Several pictures and a cross bow might decorate the walls. A

chandelier with three or four candles hung from the ceiling; it was used only

on Sundays and holidays such as Christmas. Windows were usually small and

opaque, the diamond-shaped glass enclosed in lead frames.

In the back of the dwelling would be the kitchen that in

modest houses would have another fireplace for cooking, more shelves for

plates, pots, pans, and jugs, a washbasin on top of a cabinet and a kettle of

water hanging above the basin. Water had to be carried into the house from the

nearest well or public fountain in the village. There might be a small alcove

bed in the kitchen for a child. In summer the kitchen fire was used for

cooking, but in winter the interior room fire was used for this purpose. To

maintain two fires at the same time was expensive, so the kitchen was left ice

cold in winter. Outside the kitchen door, most houses had a cistern to catch

and contain rainwater.

FIRE HAZARDS

A fire that destroyed a single farmhouse was not the end of

the world since with neighborly assistance, the family could soon construct

another dwelling. In the cities, fire could be, and often was, a disaster. To

reduce the risk, houses were often built from a frame structure and the walls

filled in with paneling consisting of twigs and branches woven together and

covered over with a plaster made of loam, mud, and cow dung.

City ordinances regulated building. Tar and pitch were

prohibited materials on the fac

a

de, and beds could not be built

within four feet of the hearth. Fires were extremely dangerous; they could

destroy a village or town in short order. Inspectors came around regularly to

check the work and, depending on the city, could be very strict looking for the

smallest deviation from the building codes.