Daily Life During The Reformation (37 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

For banquets, pies have been reported measuring as much as

nine feet in circumference with a weight of some 165 pounds. Such a pie would

have used about two bushels of flour and at least 24 pounds of butter. It would

have been stuffed with various animals such as goose, rabbit, pigeon, and fowl,

the latter usually a pheasant or peacock, was often cooked whole and presented

to the guests complete with feathers.

One dish that appeared on the royal table when the guests

were to be especially impressed was a tart filled with live birds. When it was

cut open, they flew out (having been put in just before serving).

When the court went on a hunting expedition, the

accompanying entourage included butchers; fishmongers; sellers of fruit,

vegetables, and wine; and bakers. If the hunt was conducted on meatless days,

fast horsemen would be there to ride to the coast in order to bring back fish

or shellfish for the repast.

In 1553, Elizabeth I of England had Parliament proclaim

that fish was compulsory for Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays, and during Lent.

This law helped boost the fishing industry and contributed to bringing down the

price of meat.

One popular dessert was trifle, enjoyed both at home or out

on a picnic by families of all classes and means.

TRIFLE

Take a pint of the best and thickest cream, and set it on

the fire in a clean skillet, and put into it sugar, cinnamon, and a nutmeg cut

into four quarters, and so boil it well: then put it into the dish you intend

to serve it in, and let it stand to cool till it be no more than lukewarm: then

put in a spoonful of the best earning [rennet], and stir it well about, and so

let it stand till it be cold, and then strew sugar upon it, and so serve it up,

and this you may serve either in a dish, glass, or on another plate.

Lower Classes

People of lower social standing including merchants,

artisans, and professionals, used pewter plates and dishes instead of gold and

silver. Often children served the food and generally attended to the table. In

the poorer sections of cities, laborers, street cleaners, water carriers, and

those in other menial jobs used wooden plates and bowls.

In some areas, peasants ate nothing before they started

work at sunrise and only a snack later, which had to last them until supper.

They usually produced their own food. Bees supplied honey used for sweetening

instead of sugar; meat was cured and salted; and bread and beer, staples of the

diet, were made at home. Herbs were used in the kitchens of both rich and poor.

The busy farmer’s’ wife made pickles and jams and preserved vegetables grown on

their plot. If permitted by the landlord, her husband hunted and fished to

supplement their diet.

The best produce was sold at local markets, and the family

took what was left. Itinerant merchants brought various seasonings for sale, as

well as news of the world outside the village.

The Poor

The diet of the poor was monotonous, and the peasants were

constantly undernourished. Bread, cheese, and onions sufficed in the morning;

and for their one cooked meal per day, they stirred grain in with boiling

water, cooked it slowly until the grain softened, and then added boiled roots

and vegetables to make pottage that was scooped up by coarse bread made of

barley or rye. A little meat or a slice of bacon would be a luxury.

Peasants’ food included eggs, milk, and home-grown

vegetables such as leeks, cabbage, turnips, peas, beans, and garlic. Herbs were

widely used for everything.

There are many different recipes for pottage; but most seem

to be variations on the theme of broth made of vegetables and herbs augmented

with meat. One of these is given below:

POTTAGE (after Gervase Markham)

Take some meat bones or a strip

of bacon, wash and boil well, skimming off any fat that comes to the top.

When cooked, strain and put the

meat aside.

Using the same broth, add a

couple of handfuls of cereal such as oats, barley or rye, along with some

sliced onions, lettuce, carrots, turnips, spinach, cauliflower or cabbage.

Return the meat to the pot and

add parsley, rosemary, a pinch of mace and ½ teaspoonful of sugar.

Boil all together, then cover

and simmer about ¾ hour or until done. Taste to adjust the seasonings.

Put a slice of bread in the

bottom of a soup dish and cover with pottage.

SCOTLAND

The Englishman, Fynes Moryson, whose travels took him to

Scotland in April 1598, discussed the Scottish diet, noting that they ate a lot

of kale and cabbage but not much fresh meat. When they ate mutton and geese, it

was salted (which Fynes hated), and beef, venison, grouse, and fish, mostly

salmon, were restricted to the wealthy. Porridge, stovies (a potato and meat stew),

and various cheeses were consumed by almost everyone.

They drank pure wine, although at banquets comfits

(sweetmeats made of fruit, roots or seeds, and preserved in sugar) were added.

Wine was also taken by the wealthy in the morning and during the day. Brewed

ale was a favorite drink.

Fynes attended a dinner at the house of a knight whose

servants brought meat to the table set with plates of broth in which the meat

was soaked. Those sitting at the main table, however, had chicken with prunes

instead. He did’ not think much of the cooking.

GERMANY

The free cities had a year’s supply of victuals put away in

the public houses to feed people in case the city was besieged. Moryson found

the diet of the Germans to be simple and modest, apart from their heavy drinking.

They were content with a morsel of meat and bread, preferring their own

produce, and little was imported.

Commonly served at the table was sour cabbage (crawt) and

beer boiled with bread (swoope). In upper Germany, veal and beef were served in

small quantities, but in lower Germany the meal contained bacon and large dried

savory puddings. In addition, dried fish, dried apples, and pears prepared with

a cinnamon and butter sauce were popular. The Germans used many sauces, and one

that particularly appealed to Moryson was made from cherries, served with

roasted meat. In Saxony, he experienced a meal consisting of an entire calf’s

head complete with teeth. He said it looked like the head of a monster.

Nevertheless, he enjoyed it because of the sauces accompanying it.

The Germans ate little cheese or butter, and Moryson

mentions only one cheese he found palatable that was made from goats’ milk.

Another was prepared with a round hole into which was poured some wine. It was

eaten when it was sufficiently moldy along with the maggots as “dainty

morsels.” Cheeses were strong and salty to stimulate the need for drink.

Breakfast was seldom eaten at the inns except by those

setting out on journeys who would generally take a little ginger bread and

aquavit. Moryson tells us that Germans never left the table until everything

was consumed no matter how long it took, and the worst complaint that could be

made was that there was not enough to eat. Some cities passed laws that guests

could not sit more than five hours at the table.

Invited to a wedding feast in the house of an important

citizen of Leipzig, Moryson described the supper more or less as follows:

first, he was served hot and cold roast beef with a sauce made from sugar and

sweet wine. This was followed by fried carp, then roasted mutton, then dried

pears prepared with butter and cinnamon. Next came broiled salmon and herrings

and finally a kind of bread-like English fritters with a little cheese. Bread,

sprinkled with salt and pepper was provided to promote thirst. Barrels of wine

were steadily consumed throughout the meal, and once it was finally finished,

the drinking went on until no one could stand. Moryson seemed impressed with

German drinking habits as he mentions them again and again. He tells us, for

example, in Saxony, in the evening, men reeled from one side of the street to

the other, stumbled and fell in the dirt, jostled every post, pillar, and

person while trying to walk, and the gates of the city seemed too narrow for

them to pass through. Yet it was no shame to be so drunk, nor to urinate under

the table at the inn or in bed. It was not uncommon to fall out of the saddle

when trying to ride under the influence of too much wine or beer.

A

German Baptismal Feast

On special occasions, in a German city such as Nurnberg, it

was customary to invite family and friends for a prodigious feast. On December

10, 1549, for example, at the baptism of Paul Behaim II, 36 pints of mead, 48

pastries, 10 pints of new wine, and 7 of superior dark red wine were served

along with more pastries and dates; three days later, two tables of guests were

served 17 boiled and salted fish, a rabbit, 2 chickens, 24 geese, 2 ducks, 2

doves, bacon, 2 capons, white bread, fruit, 7 pints of new wine and 7 of

year-old wine. Six weeks after the birth, neighbors and laborers were sent

gifts that included pork, venison, other wild game, lard cake, wine, and (for

some) expensive Westphalian ham. The reason for this last benificence was to

proclaim that the mother had now recovered and returned to administration of

the household.

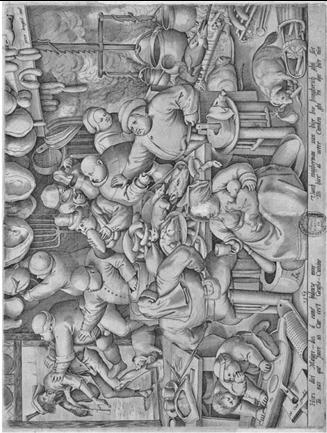

La Cocina Pobre (“The Poor

Kitchen”). Pieter van der Heyden, 1563.

La Cocina Rica (“The Rich

Kitchen”). Pieter van der Heyden, 1563.

THE NETHERLANDS

For a main meal, sliced artichokes, beans, cabbage,

cauliflower, carrots, onions, peas, and other vegetables, along with stale

bread were made into a stew or hodgpodge. When the pig was killed in the

autumn, the meat was sold or salted, and some was made into sausages. Mustard

was a favorite sauce eaten with sausages and tripe. Wealthy people ate wild

fowl and venison, others consumed fish, a staple food, purchased in the market

or from a fishmonger making the rounds of the neighborhood. Fresh fish was not

always as fresh as claimed, but the housewife could usually find dried cod and

smoked herring or mussels. Bread, butter, and cheese were eaten by everyone,

and specialties included mushrooms, frogs’ legs, and oysters.

Breakfast was generally not eaten except by children who

might devour a piece of bread before going to school or work. The bakers’

antiquated ovens were unreliable, and bread was not always ready at a given

hour; only when the baker blew his horn, was fresh bread ready to be bought.

When buying bread, a cloth was taken to carry it, and before cutting it, the

wife would make the sign of the cross and then carve one into the loaf.

Gentleman’s bread was white, made of wheat; this was also

the bread given to someone about to be executed. The less well-off ate black

bread, made from rye. In the country, people made their own rye bread adding

salt, pork fat, raw onions, and cheese to improve the taste.

Small birds were often caught by placing a board, raised at

one end by a stick, under which a few seeds were sprinkled. The stick was

attached to the house by a string, and the birds were trapped when the string

was pulled and the board crashed down on them. In addition, pots hung from the

gutter of the roof for nesting birds, generally starlings, and when the young

birds were nearly ready to leave the nest, they were gathered up and cooked.